Since the arrival of the internet, network effects have become the most important source of value creation in the networked economy. Companies built on top of network effects have become the dominant players in the digital world, having created 70% of the value in tech over the past two decades.

Our understanding of network effects underlies much of what we do at NFX. As entrepreneurs, we started 10 network effect businesses worth over $10 billion, and we’ve previously published two of the most comprehensive online references on network effects:

- The NFX Manual — a deep dive into the 13 known types of network effects

- The NFX Bible — an in-depth explanation of all network effect-related concepts

Today, we’re releasing the third part of this series: the NFX Archives. Think of it like required, foundational reading for mastering how network effects work. These are the papers, articles, and books we read that proved to be invaluable for building strong, highly defensible companies.

This repository is always evolving and growing, and so we’ll continue to update and expand it. For now, there are three parts:

For your convenience, we’ve summarized the articles and their main points. If you want a deeper dive on any particular resource, we encourage you to click through and read the full article. We’ve found every article in this list to be worth the time investment.

We believe world-class Founders see what others do not. Our mission is to empower them in building companies that endure. We hope you find these resources just as invaluable to your journey as they were to ours.

Part I: Network Science

Network science, also known as graph theory in mathematics, is the academic study of complex networked systems and their real-world properties. This section includes a thorough survey of network fundamentals: what we currently know about the structure, behavior, dynamics, categories, and characteristics of different types of networks. For those interested, this collection of academic resources will give you the ability to look past the surface and understand the underlying patterns of our networked world at a deeper level.

1. The Small-World Problem

Stanley Milgram, Psychology Today, 1967

Summary

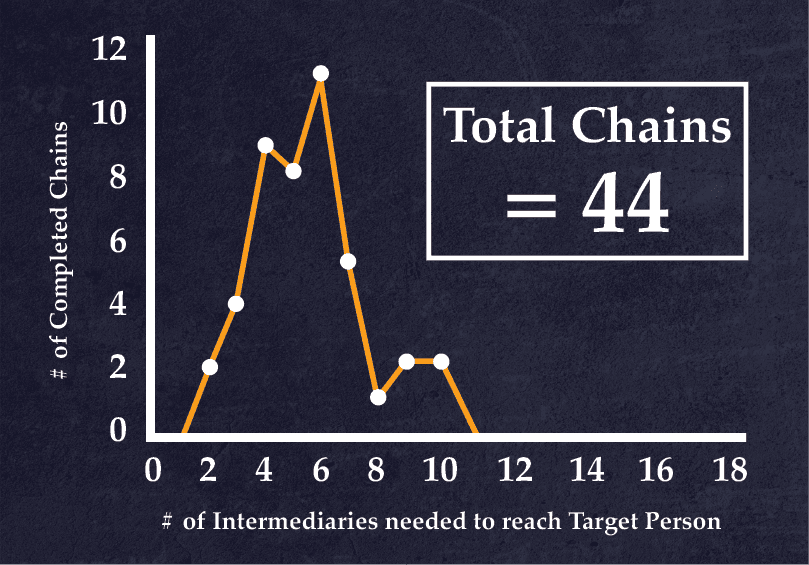

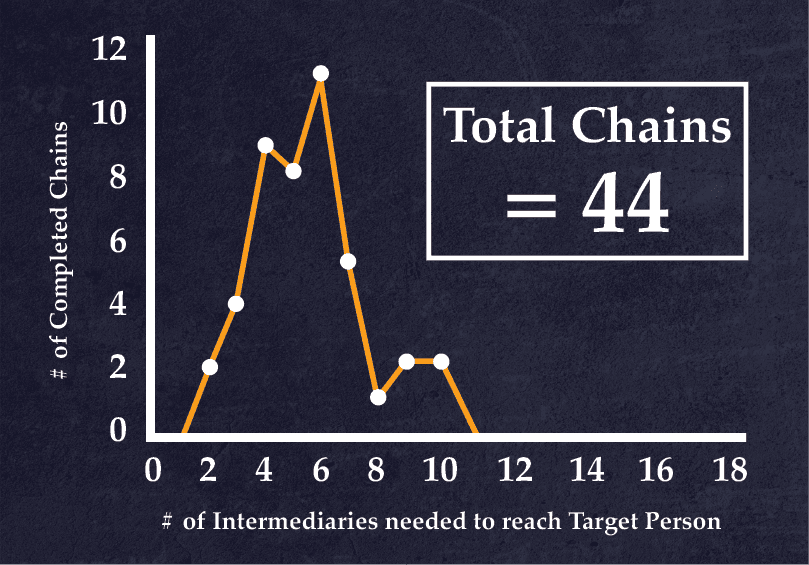

The earliest study to ever verify the existence of the “small-world phenomenon”, i.e. the very low number of intermediaries needed to connect two people in massive networks of millions of people (in this case, the United States back in the 1960s with a population of ~ 200 million). Milgram’s method was basically to select two people on opposite sides of the country at random and find out how many intermediaries it would take to forward a folder from person A (the “starting person”) to person B (the “target person”). With this simple experiment in a pre-internet world, Milgram was able to establish a median path length of 6 (5 intermediaries) across the population of the United States, corresponding to the popular phrase “six degrees of separation” (later popularized by playwright John Guare).

Why It Matters

Milgram’s article was the first empirical study of personal direct networks, and set the stage for broader studies of real-world networks that came afterwards. It foreshadowed many topics expanded on by resources later in this guide, such as the importance of acquaintances (the strength of weak ties) in reducing path length, the existence of small-world networks, and the differential importance of nodes and paths. One of the first social networks on the internet, sixdegrees.com, was named after the small-world phenomenon explored by Milgram. So, too, was the actor Kevin Bacon’s charity sixdegrees.org, a reference to the 1994 meme “six degrees of Kevin Bacon” which referred to the small-world phenomenon in the Hollywood actor network.

Selected Quotations

- “Almost all of us have had the experience of encountering someone far from home who, to our surprise, turns out to share a mutual acquaintance” – 61

- “Starting with any two people in the world, what is the probability that they will know each other?” [the ‘small-world problem’] – 62

- “We learned that the chain [the distance between two randomly selected individuals in the United States] varied from two to 10 intermediate acquaintances, with the median at five.” – 65

- “Each of us is embedded in a small-world structure. It is not true, however, that each of our acquaintances constitutes an equally important basis of contact with the larger social world… some friends are relatively isolated, while others possess a wide circle of acquaintances [i.e. weak ties], and contact with them brings us into a far-ranging network.” – 66

- “Social communication is sometimes restricted less by physical distance than by social distance.” – 66

- “A very interesting theorem based on the model of the small world… states that if two persons from two different populations cannot make contact, then no one within the entire population in which each is embedded can make contact with any person in the other population.” – 67

2. The Strength of Weak Ties

Mark. S Granovetter, American Journal of Sociology 1973

Summary

In one of the most heavily cited sociology articles ever published (with more than 50,000 citations as of December 2018), “the Strength of Weak Ties” was one of the foundational documents of network science. In it, Mark Granovetter argues that so-called “weak ties” are responsible for connecting nodes in different network cliques or “clusters”, because strong ties are usually shared by other members of the same cluster. In other words, weak ties — e.g. acquaintances — are the “bridges” between nodes in a network that don’t usually interact; and in performing that function, they reduce the overall average degree of separation, or path length, between any two nodes in a network.

Why It Matters

The counterintuitive “strength of weak ties” argument has many important implications for Founders looking to build networked products. For one thing, it shows that enabling users to form weak ties easily is probably crucial for the cohesion of a network. Weak ties could be an effective countermeasure against the development of algorithmic filter bubbles, which can have harmful externalities and damage the health of the user ecosystem. But the ability to form weak ties must be tempered against the need to avoid network pollution which can result from too many weak ties.

Selected Quotations

- “The strength of a tie is a (probably linear) combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie.” – 1361

- “The stronger the tie between A and B, the larger the proportion of individuals… to whom they will both be tied” – 1362

- “Overlap in their friendship circles is predicted to be least when their tie is absent, most when it is strong, and intermediate when it is weak.” – 1362

- “If strong ties A-B and A-C exist, and if B and C are aware of one another, anything short of a positive tie would introduce a ‘psychological strain’ into the situation since C will want his own feelings to be congruent with those of his good friend, A, and similarly, for B and his friend, A.” – 1362

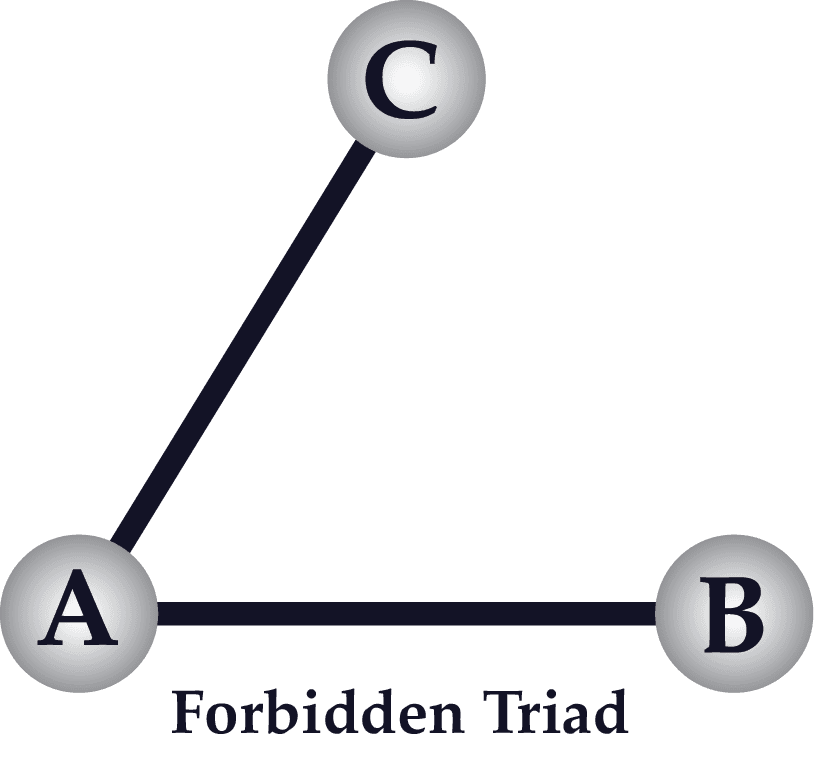

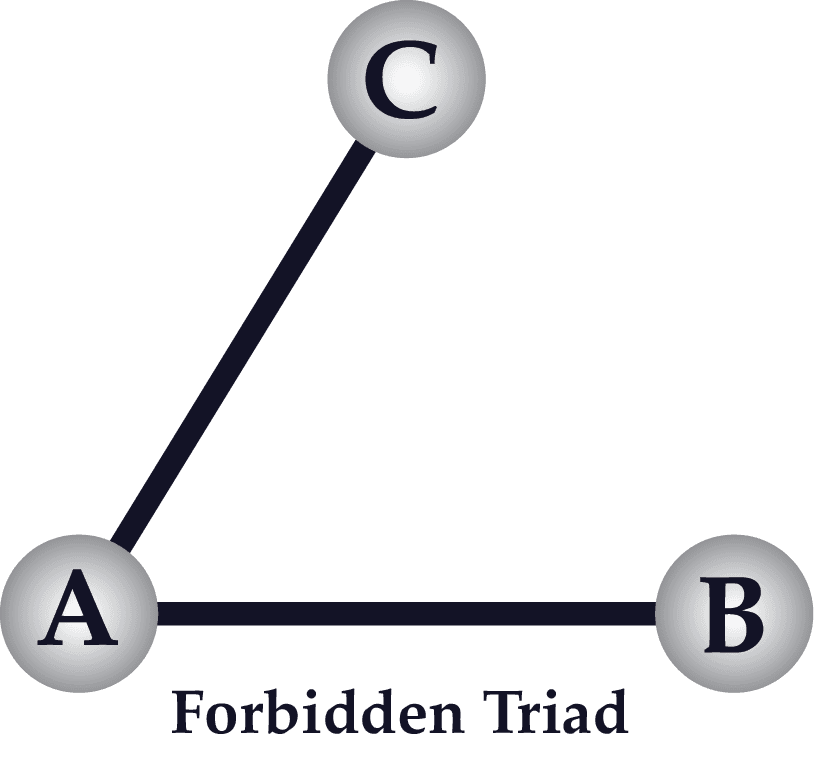

- “The triad which is most unlikely to occur, under the hypothesis stated above, is that in which A and B are strongly linked, A has a strong tie to some friend C, but the tie between C and B is absent [a description of the ‘forbidden triad’ pictured below]” – 1363

3. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital

James S. Coleman, University of Chicago Press, 1988

Summary

This paper attempts to formalize the concept of “social capital” — a parallel concept to financial capital, physical capital, and human capital. From a network perspective, the thesis can be interpreted as a description of the protocols and payload of exchange between nodes in a network that isn’t mediated by currency (i.e. a network that’s not a market). Social capital, Coleman observes, performs the same function as in such networks as financial capital (currency + transaction systems) for markets. The author proposes that social capital arises from a combination of network structure and the strength of ties within a network, and classifies several different categories of social capital.

Why It Matters

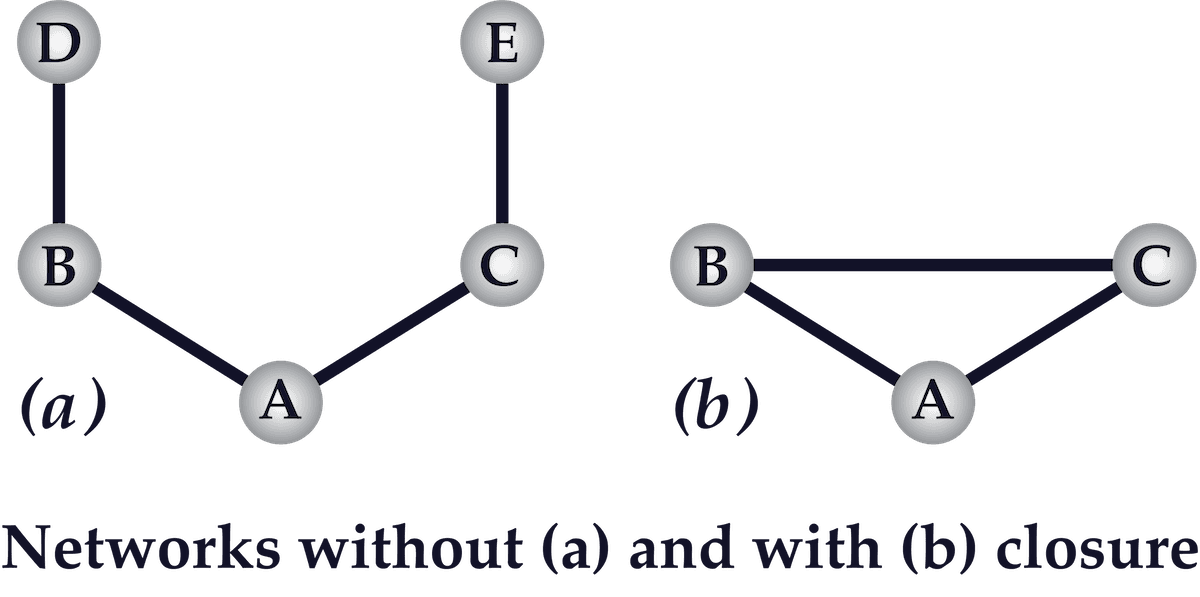

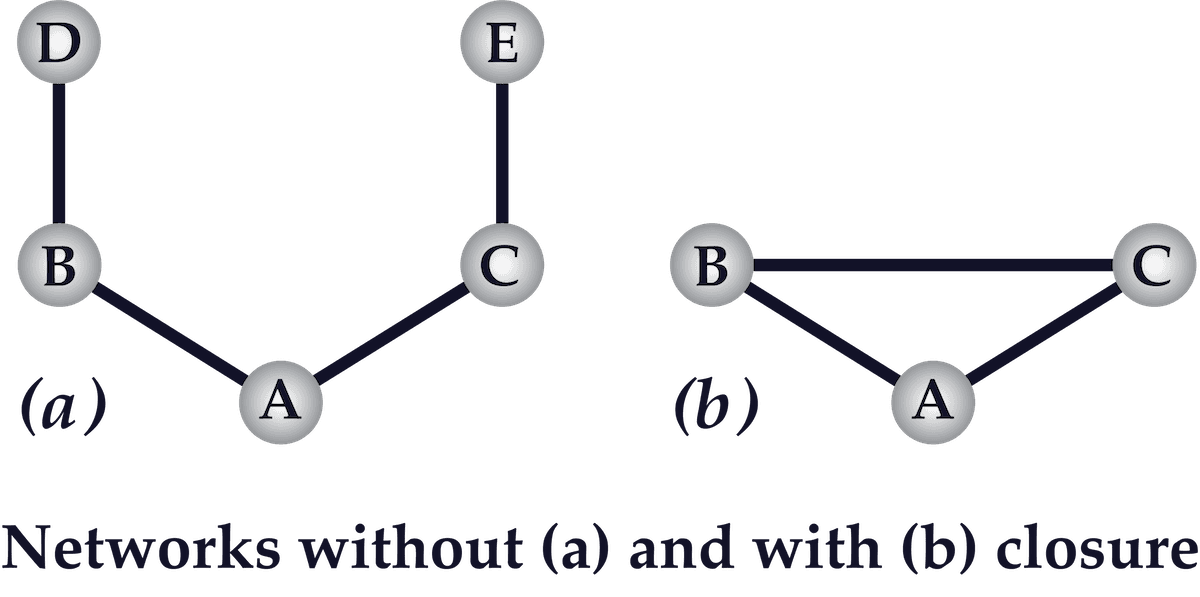

This paper demonstrates the importance of network structure to the formation of norms and trustworthiness within a network and reveals how the ability to substitute reputation and obligation for financial credit and insurance can work within tight, closed networks (such as wholesale diamond markets, as discussed in this paper). The author uses the terms “closed” and “closure” to indicate the existence of network clusters with a high proportion of overlapping strong ties (i.e. a high clustering coefficient). The implications for building networked products are profound for Founders who want to create an effective self-regulating community (e.g. certain subreddits) — instead of having to hire full-time content monitors or algorithmic censors for user-generated content (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube).

Selected Quotations

- “Social capital is part of a general theoretical strategy discussed in the paper: taking rational action as a starting point but rejecting the extreme individualistic premises that often accompany it.” – S95

- “Three forms of social capital are examined: obligations and expectations, information channels, and social norms.” – S95

- “If we begin with a theory of rational action… then social capital constitutes a particular kind of resource available to an actor.” – S98

- “Like other forms of capital, social capital is productive, making possible the achievement of certain ends that in its absence would not be possible.” – S98

- The consequence of closure is that norms can be reinforced by common ties instead of having to be enforced unilaterally. Closure provides “a set of effective sanctions that can monitor and guide behavior.” – S107

- “Reputation cannot arise in an open structure… closure creates trustworthiness in a social structure.” – S108

4. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks

Duncan J. Watts & Steven H. Strogatz, Nature 1998

Summary

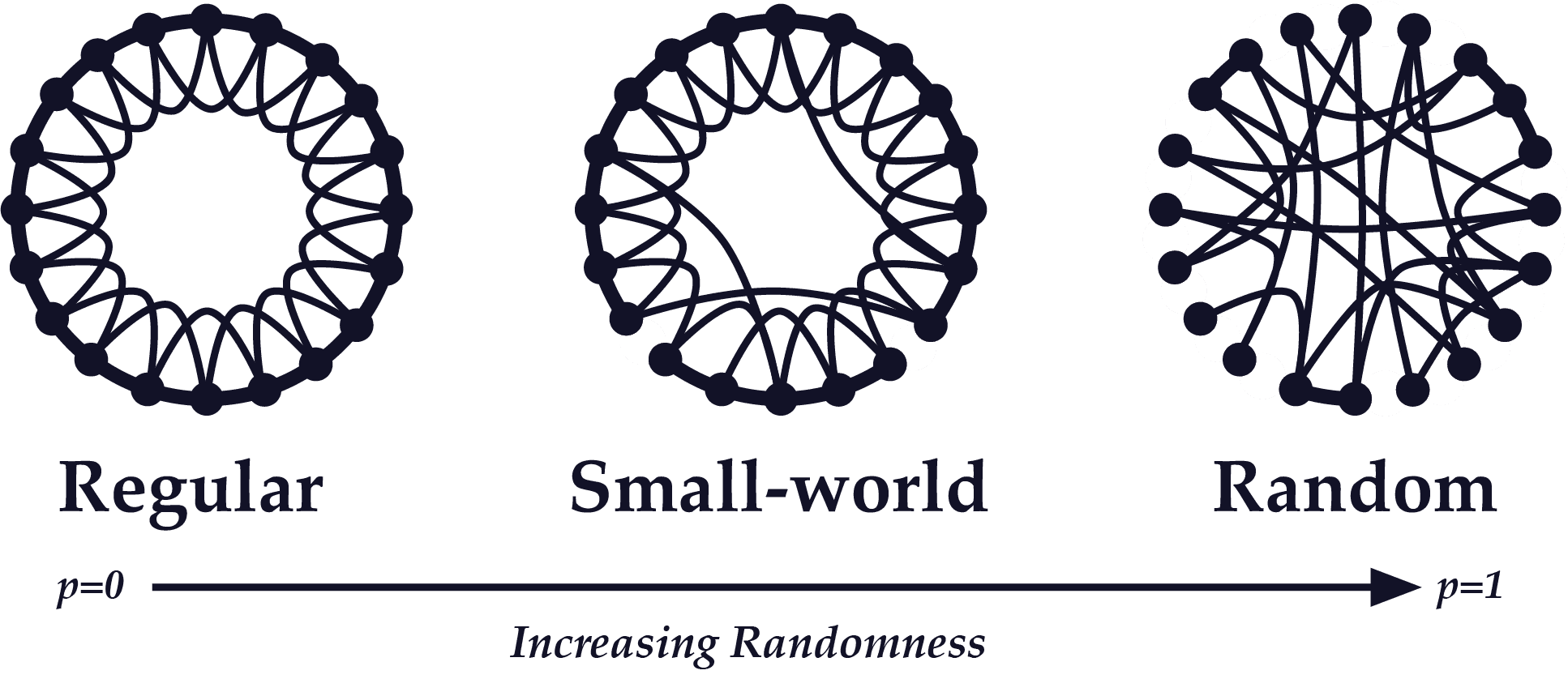

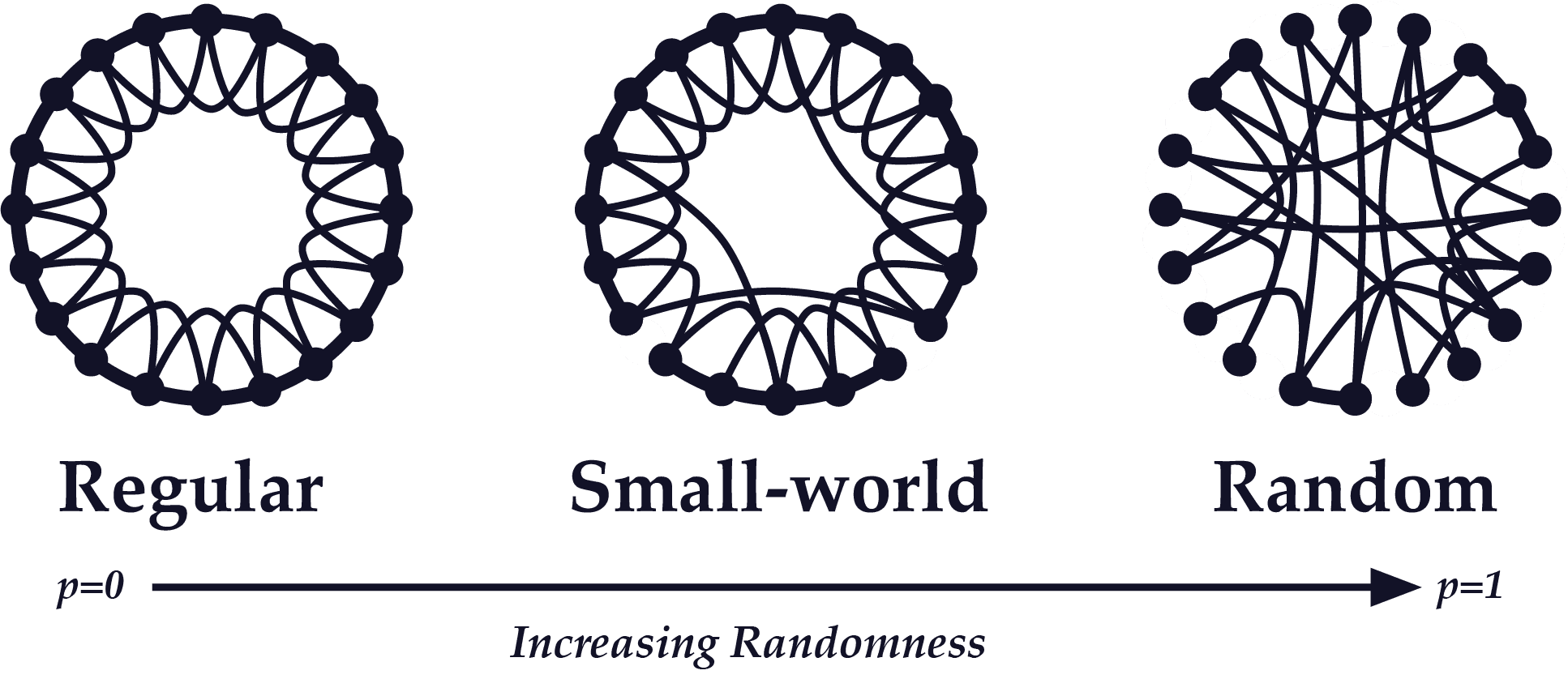

This heavily cited paper extends the “strength of weak ties” thesis by asking whether the “small-world” phenomenon (networks where there are relatively few degrees of separation between any two given individuals) can exist in networks with a high degree of clustering (cliques or highly interconnected local neighborhoods within a network). The authors show that, with just a few “short-cuts” (i.e. bridges) connecting faraway neighborhoods within a network, even a highly clustered network can have a low characteristic path length. Their name for such a network is a “small-world network”, also known as the Watts-Strogatz model.

Why It Matters

The “small-world network” thesis shows that highly regular networks with many strong ties and few weak ties can still be relatively well-connected, meaning that even if the users of a social network (for example) mostly only interact with a small circle of other users, the larger network can still be relatively cohesive as long as just a few “short-cut” connections exist. The Watts-Strogatz model thus provides a solution to maintaining network cohesion without risking network pollution — allowing users to make short-cut connections to distant users while preventing the need for an inflated amount of irrelevant connections (e.g. LinkedIn).

Selected Quotations

- Small-world networks are regular networks that have been“‘rewired’ to introduce increasing amounts of disorder… [they] can be highly clustered, like regular lattices, yet have small characteristic path lengths, like random graphs… we call them ‘small-world’ networks, by analogy with the small-world phenomenon (popularly known as six degrees of separation).” – 440

- “Infectious diseases spread more easily in small-world networks than in regular lattices” – 440

- There’s a “broad interval of randomness” over which a network’s characteristic path length at a given level of randomness is almost as small as the characteristic path length of a completely random network, but the network’s clustering coefficient is greater than the clustering coefficient of a random network. – 440

- “These small-world networks result from the immediate drop in [characteristic path length] caused by the introduction of a few long-range edges. Such ‘short-cuts’ [i.e. bridges] connect vertices that would otherwise be much farther apart [than a totally random network].” – 440

5. Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks

Albert-László Barabási and Réka Albert, Science, 1999

Summary

In contrast to both Watts and Strogatz’s small-world network model and to Erdős–Rényi random graph model, Albert-László Barabási and Réka Albert show that in large, complex networks, highly connected vertices have a large chance of occurring and of dominating connectivity in a network. In other words, a small number of “rich” nodes accrue most of the links, which explains the scale-free, power-law distribution of node degrees observed within complex networks.

Why It Matters

The main importance of this article is that it’s one of the first to evaluate network topology by using data from real-world networks, and it concludes that the reason for the existence of scale-free networks in the real world (instead of random graphs) is a phenomenon Barabási calls preferential attachment. Preferential attachment happens when, as networks grow, new nodes disproportionally tend to form links with nodes that already have a high degree of connectivity, giving complex networks a self-organizing quality. In other words, in real-world networks, well-connected nodes tend to get even more connected as the network scales.

Selected Quotations

- “A common property of many large networks is that the vertex connectivities [i.e. links] follow a scale-free power-law distribution.” – 509

- “This feature was found to be a consequence of two generic mechanisms: (i) networks expand continuously by the addition of new vertices, and (ii) new vertices attach preferentially to sites that are already well connected.” – 509

- “The development of large networks is governed by robust self-organizing phenomena that go beyond the particulars of the individual systems.” – 509

- “Traditionally, networks of complex topology have been described with the random graph theory.” – 510

- “Here we report on the existence of a high degree of self-organization characterizing the large-scale properties of complex networks.” – 510

- “Independent of the system and the identity of its constituents, the probability P(k) that a vertex in the network interacts with k other vertices decays as a power law… This result indicates that large networks self-organize into a scale-free state.” – 510

- “Because of the preferential attachment, a vertex that acquires more connections than another one will increase its connectivity at a higher rate; thus an initial difference in the connectivity between two vertices will increase further as the network grows.” – 511

6. The structure and function of complex networks

M. E. J. Newman, University of Michigan Department of Physics 2003

Summary

A well-written, thorough overview of academic literature on network science, covering everything from clustering coefficient formulas to models of network resilience. Although much of the article is technical, containing mathematical models and formulae of different network phenomena, it’s still well worth a skim for Founders looking for an all-inclusive resource to familiarize themselves with the foundations of network science and how network properties can be statistically studied.

Why It Matters

There are many gems with real-world implications in this article. In a section about network resilience, for example, Newman points out that most real-world networks can endure the removal of nodes at random without much damage, but are very vulnerable to the removal of high-degree nodes. So in other words, key users with high network centrality are the key to the overall health of the network— making them much more valuable than marginal nodes without many connections. If a key user or group of key users have high enough network centrality, they could even become indispensable for the health of the network. This implies that Founders should do whatever they can to incentivize users with high degree centrality to stay, and should treat it as a very serious problem when they notice movement of such users away from their network.

Selected Quotations

- “Graphs may also evolve over time, with vertices or edges appearing or disappearing, or values defined on those vertices and edges changing.” – 4

- “[There are] four loose categories of networks: social networks, information networks, technological networks and biological networks.” – 5

- The small-world effect: “the fact that most pairs of vertices in most [real-world] networks seem to be connected by a short path through the network.” – 9

- The formula for calculating a network’s clustering coefficient: multiply the number of triangles (sets of nodes each of which is connected to each of the others) in the network by 3, then divide that by the number of connected triples (single nodes with links running to an unordered pair of other nodes) – 11

- “Most networks are robust against random vertex [node] removal but considerably less robust to targeted removal of the highest-degree vertices [nodes].” – 16

- “In most kinds of networks there are at least a few different types of vertices, and the probability of connection between vertices often depends on types.” – 16

7. Four Degrees of Separation

Facebook Research, June 2012

Summary

Utilizing Facebook user data, a research team was able to observe an average distance (path length) of 4.74 across their network, meaning that there were on average 3.74 degrees of separation between any two people on the Facebook network —- the largest ever studied up until the time of this paper.

Why It Matters

Founders can take several lessons away from this paper. Firstly, it’s significant that a technology company was able to single-handedly reduce the characteristic path length of a significant portion of humanity. The implications of that for the diffusion of ideas are pretty vast, and the cohesion of the Facebook network probably goes towards explaining the high efficacy of Facebook advertising. Secondly, it’s worth noticing that Facebook devoted the time and resources to conduct this study. Facebook knows their network is a goldmine, they’re familiar with the basic concepts of graph theory, and they’re applying network science to make the best use of their network. If Zuck cares about this stuff, you probably should too.

Selected Quotations

- “Results of the first world-scale social-network graph-distance computations, using the entire Facebook network of active users (~721 million users, ~69 billion friendship links). The average distance we observe is 4.74, corresponding to 3.74 intermediaries or “degrees of separation” – 45

- “The networks we are able to explore are almost two orders of magnitude larger than those analysed in the previous literature” – 45

- “We also observe both a stabilisation of the average distance over time” – 45

- “During the fastest growing years of Facebook our graphs show a quick decrease in the average distance, which however appears now to be stabilizing… at the same time, density was going down steadily… we thus see the small-world phenomenon fully at work: a smaller fraction of arcs connecting the users, but nonetheless a lower average distance.” – 51 / 52

- “In an absolute sense [on Facebook], geographical concentration increases density” – 51

8. Three and a half degrees of separation

Facebook Research, February 2016

Summary

An update of Facebook’s initial study in 2012, this follow-up shows that the trend towards fewer degrees of separation between users in the Facebook network continued even as the size of the network more than doubled, from 721 million active users to 1.59 billion.

Why It Matters

Another data point demonstrating the increasingly networked nature of the world at large as a result of internet-enabled networks like Facebook. It is striking that Facebook sees a reduction in characteristic path length across their network as an unambiguous sign of progress, as such a trend falls in line with their mission statement to make the world more “open and connected”. However, some of the downsides of an increased ease of diffusing ideas across Facebook made themselves known the very year this study was published.

Selected Quotations

- “We’ve crunched the Facebook friend graph and determined that the number [of degrees of separation] is 3.57.”

- “Each person in the world (at least among the 1.59 billion people active on Facebook) is connected to every other person by an average of three and a half other people.”

- “Within the US, people are connected to each other by an average of 3.46 degrees.”

- “Our collective ‘degrees of separation’ have shrunk over the past five years”.

9. Network Science

Albert-László Barabási, 2016

Summary

Barabási’s “Network Science” is one of the most comprehensive resources available on network science. It covers most network fundamentals, from network distance to degree distribution, and walks you through the underlying math. Barabási also includes an expanded discussion of his theory of “preferential attachment”, which helps show why a wide variety of network structures display the scale-free property.

Why It Matters

Network Science is worth skimming in its entirety for Founders who want a solid fundamental grasp of both graph theory and network science, but special attention is due to Chapter 5, “The Albert-Barabási Model”, which introduces the concept of preferential attachment. Here, Barabási observes that network degrees (links per node) tend to follow a Pareto “80/20” distribution rather than a Poisson distribution as might be expected, if extrapolating from random graph theory. He explains this by pointing out that nodes prefer to link to connected nodes (nodes with a high relative degree) — leading to a small number of nodes with a large number of links. Another observation Founders might find useful is that social networks tend to be assortative, meaning that hubs (high degree nodes) tend to link to each other and, at the same time, avoid linking to low degree nodes.

Selected Quotations

- “Networks permeate science, technology, business and nature to a much higher degree than it may be evident upon a casual inspection. Consequently, we will never understand complex systems unless we develop a deep understanding of the networks behind them.” – 1.2

- Vulnerability due to interconnectivity: “Being part of a network has its catch… local failures may not stay local any longer. Their impact can travel along the network’s links and affect other nodes, consumers and individuals apparently removed from the original problem. In general interconnectivity induces a remarkable non-locality. It allows information, memes, business practices, power, energy, and viruses to spread on their respective social or technological networks, reaching us, no matter our distance from the source.” – 1.1

- “WIth an estimated size of over one trillion documents (N ≈ 1012), the Web is the largest network humanity has ever built. It exceeds in size even the human brain (N ≈ 1011 neurons).” – 4.1

- “The 80/20 rule is present in networks as well: 80 percent of links on the Web point to only 15 percent of webpages; 80 percent of citations go to only 38 percent of scientists; 80 percent of links in Hollywood are connected to 30 percent of actors. Most quantities following a power law distribution obey the 80/20 rule.” – 4.2

- Preferential attachment: “In most real networks new nodes prefer to link to the more connected nodes” – 5.2. This explains the existence of a power law in degree distribution across a diversity of complex systems

10. The Square and the Tower

Niall Ferguson, 2018

Summary

The Square and the Tower is about the evolution of social and political networks and hierarchies throughout history. Although most of the book is about history, in chapters 5 through 8 Niall Ferguson, who’s an excellent writer, explains most of the major network science concepts in an accessible way — from the origins of graph theory right up to the present. Ferguson also recaps a lot of the relevant academic literature in easy-to-understand, plain language, including some resources covered elsewhere in this article. Topics of interest include: scale-free networks, modular networks, hierarchies, network vulnerabilities, and inter-network dynamics.

Why It Matters

Founders looking for a well-written, accessible take on network science will find chapters 5-8 of the Square and the Tower valuable. Throughout the book, Ferguson deftly applies abstract network science concepts in analyzing real events, which may prove inspirational for Founders looking to apply theoretical network concepts in a real-world context. For example, his insights on network structure have important implications for building virality. As we’ve written in the past, it’s not always the product itself that leads to rapid dissemination. Targeting the right network cluster can be more important — which is why we urge our Founders to find the white-hot center.

Selected Quotations

- “Network structure can be as important as the idea itself in determining the speed and extent of diffusion” – 34

- “In the process of going viral, a key role is played by nodes that are not merely hubs or brokers but ‘gate-keepers’ — people who decide whether or not to pass information to their part of the network. Their decision will be based partly on how they think that information will reflect back on them.” – 34

- “A complex cultural contagion… first needs to attain a critical mass of early adopters with high degree centrality (relatively large numbers of influential friends).” – 35

- “Far from being the opposite of a network, a hierarchy is just a special kind of network” – 39

- A seemingly random network can evolve with astounding speed into a hierarchy” – 40

Part II: Network Effects

In the past, NFX has published some of our frameworks for understanding network effects, including the NFX Bible and the NFX Manual. In addition, we’ve done case studies examining specific companies to provide commonly understood examples of how our frameworks map to the real world, including:

We’ve also made known different facets of network effects, such as

- Reinforcement: The Hidden Key to Building Iconic Tech Companies

- The Next 10 Years Will Be About Market Networks

- 19 Tactics to Solve the Chicken-or-Egg Problem and Grow Your Marketplace

We do all this because we think it benefits Founders in their efforts to build transformative companies. There’s still much more ground for us to cover, as networks and network effects are a broad subject.

But, in the meantime, here are some of the best supplemental — and perhaps more academic — resources. There’s a surprising amount of value here for those Founders who are willing to take the time.

11. Increasing Returns and the New World of Business

W. Brian Arthur, Harvard Business Review, July-August 1996

Summary

W. Brian Arthur, one of the first economists to work on complexity theory, was also early to recognize the importance of network effects in his seminal work on increasing returns, which he began in the 1970s.

In this classic HBR summary of his work on increasing returns, Arthur distinguishes two types of markets. One, which he calls the “Halls of Production”, are markets subject to diminishing returns. These markets, he says, act in a way consistent with traditional economics: diminishing returns impose natural limits on market share, meaning that margins stay low and prices stay competitive. He associates the “Halls of Production” with manufacturing and traditional industry.

Increasing returns markets, on the other hand, tend to produce winner-take-most effects, where a single winner takes most of the value in a market. This increasing returns dynamic, according to Arthur, characterizes one part of the economy in particular: high technology. He calls this part of the economy the “Casino of Technology”.

Why It Matters

Like NFX, Arthur argues that Founders looking to play at the “Casino of Technology” need to learn how to actively manage increasing returns if they want to win. It’s not enough to have superior technology or to be the first mover in a market — you have to understand what Arthur calls the local market “ecology” (i.e. the network of adjacent or enabling technologies).

He also argues that in high-volatility, increasing returns markets, you have to become a “wizard of precognition” to see “the shape of the next game.” Constant adaptation and correctly identifying the shape of things to come are the skills for winning in increasing returns markets, rather than the “Halls of Production” skills of incremental optimization, driving down costs and increasing quality.

(Side note: W. Brian Arthur did an a16z podcast with Marc Andreessen and Sonal Chokshi in 2018 where he discusses the same ideas in an updated context. It’s worth a listen for Founders who prefer an audio format).

Selected Quotations

- “The underlying mechanisms that determine economic behavior have shifted from ones of diminishing returns to ones of increasing returns.”

- “Increasing returns are the tendency for that which is ahead to get further ahead”

- “We can usefully think of two economic regimes or worlds: a bulk-production world … operating according to principles of diminishing returns, and a knowledge-based part of the economy … operating under increasing returns.”

- “the art of playing the tables in the Casino of Technology is primarily a psychological one. What counts to some degree—but only to some degree—is technical expertise, deep pockets, will, and courage. Above all, the rewards go to the players who are first to make sense of the new games looming out of the technological fog, to see their shape, to cognize them. Bill Gates isnot so much a wizard of technology as a wizard of precognition, of discerning the shape of the next game.”

- “You cannot optimize in the casino of increasing-returns games. You can be smart. You can be cunning. You can position. You can observe. But when the games themselves are not even fully defined, you cannot optimize. What you can do is adapt.”

- “Unlike products of the processing world, such as soybeans or rolled steel, technological products exist within local groupings of products that support and enhance them. They exist in mini-ecologies.”

12. A Theory of Interdependent Demand for a Communication Service

Jeffrey Rohlfs, The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 1974

Summary

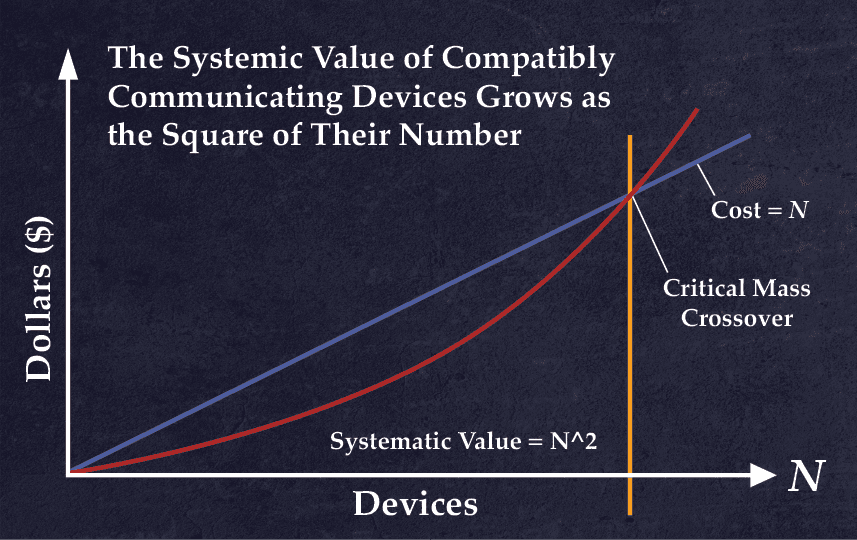

Perhaps the first in-depth academic study of network effects, this paper examines what it calls “dynamic demand” for communication services. The authors noticed early on that the demand for a communication service scales with the size of the service, as each marginal subscriber improves the utility of the service for all other subscribers. This concept gave rise to the term “demand-side economies of scale”, which is one aspect of what we now call network effects.

Why It Matters

The most interesting nugget in this paper for Founders today has to do with pricing models — even as far back as 1974, the telecommunications industry figured out the value of “growth at all costs”, even if it meant offering pricing that didn’t make sense if you don’t take externalities (network effects) into account.

Selected Quotations

- “The utility that a subscriber derives from a communications service increases as others join the system.” – 16

- “This is a classic case of external economies in consumption.” – 16

- “A still lower price, perhaps much lower, might be justified if the externalities are taken into account. The total benefits that all subscribers derive from the expansion of the service may be sufficient to justify the incremental costs— even if the new subscribers are unwilling to pay the entire incremental costs.” – 17

- “[In] a dynamic demand model… [new subscribers joining the network] increases the incremental utility of the service and induces marginal nonusers to join. That in turn induces further growth, etc., etc.” – 17

13. Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets

Rochet and Tirole, European Economic Association, 2003

Summary

This article develops several pricing structure formulae for 2-Sided Platforms (also applicable to 2-Sided Marketplaces), observing how various governance structures and network economics change the optimal pricing structures platforms should employ to attract both sides simultaneously.

Why It Matters

This article is mostly of interest to Founders who are working with 2-sided networks and want a way to set pricing strategy that’s based on an understanding of network economics. The authors have done a good job of accounting for the dynamics that make multi-sided networks more complicated to manage from a pricing standpoint.

Selected Quotations

- “Many if not most markets with network externalities are two-sided. To succeed, platforms … must ‘get most sides of the market on board.’ Accordingly, platforms devote much attention to their business model, that is, to how they court each side while making money overall.” – 990

- “The interaction between the two sides give rise to strong complementarities… our theory is a cross between network economics, which emphasizes such externalities, and the literature on multi-product pricing, which stresses cross-elasticities.” – 991

- “Monopoly and competitive platforms design their price structure so as to get both sides on board.” – 1013

- “An increase in multihoming on the buyer side facilitates steering on the seller side and results in a price structure more favorable to sellers.” [because in order to differentiate supply to heighten switching costs for multi-tenanting demand-side users, platforms typically incentivize the supply side to stay with them with favorable price structures or increased visibility in the marketplace and thus increased velocity] – 1013

- “The presence of marquee buyers (buyers generating a high surplus on the seller side) raises the seller price and (in the absence of price discrimination on the buyer side) lowers the buyer price.” – 1013

- “Captive buyers [demand] tilt the price structure to the benefit of sellers.” – 1013

14. Network Externalities (Effects)

S.J. Liebowitz, The New Palgrave’s Dictionary of Economics and the Law, 1998

Summary

A good overview of the early literature around network effects, including discussion of the mechanics of both positive and negative network effects and their market implications. Liebowitz also coins some helpful network vocabulary, such as when he posits a “congestion externality” (which we’ve written about as well, calling it Network Congestion).

Why It Matters

Liebowitz is excellent here at breaking down network effects to their basic elements and describing them precisely. For example, the distinction between what he calls “autarky value” (standalone value of a product without other users) and the “synchronization value” of a product (the value a product brings through interaction with other users of the product) is a helpful mental model for Founders to strategize networked product features.

He also emphasizes the difference between network externalities and network effects. True externalities are the unrealized secondary consequences of the platform and don’t benefit the platform. They are external. If the owners of a platform are able to move those externalities onto the platform (internalize them), then those externalities become true network effects, and they benefit the platform owners. This is somewhat of a semantic point, except that it shows the strategic importance of designing the product and business model so you capture the value you’re creating as a Founder.

Selected Quotations

- “Network externality has been defined as a change in the benefit, or surplus, that an agent derives from a good when the number of other agents consuming the same kind of good changes.”

- “This allows, in principle, the value received by consumers to be separated into two distinct parts. One component, which in our writings we have labeled the autarky value, is the value generated by the product even if there are no other users. The second component, which we have called synchronization value, is the additional value derived from being able to interact with other users of the product, and it is this latter value that is the essence of network effects.”

- “Network effects should not properly be called network externalities unless the participants in the market fail to internalize these effects… When the owner of a network (or technology) is able to internalize such network effects, they are no longer externalities.”

- “Though economists have long accepted the possibility of increasing returns, they have generally judged that except in fairly rare instances, the economy operates in a range of decreasing returns. Some proponents of network externalities models predict that as newer technologies take over a larger share of the economy, the share of the economy described by increasing returns will increase.”

- “Network externality models often feature particular outcomes: Survival of only one network or standard, unreliability of market selection, and the entrenchment of incumbents.”

15. Metcalfe’s Law is Wrong

Bob Briscoe, Andrew Odlyzko and Benjamin Tilly, IEEE Spectrum, 2006

Summary

An arguably failed attempt to disprove Metcalfe’s Law, given the authors’ own admittance that “our valuation of a communications network… cannot be proved” from first principles, and also given that the authors didn’t try to prove their point using real-world data (as Metcalfe would later do by way of rebuttal — see below). Still, it’s an interesting look at Metcalfe’s Law, and the authors suggest an alternative formula for valuing network effects, which grows at a slower logarithmic rate as the network scales.

Why It Matters

This resource is primarily useful for its critical examination of the underlying axioms of Metcalfe’s Law, chiefly by using thought experiments. In particular, it points out that the apparent flaw in both Metcalfe’s Law and Reed’s Law is the assumption that all connections or groups (clusters) within a network have equal value — a “common-sense argument that suggests Metcalfe’s and Reed’s laws are incorrect”. But, as Metcalfe shows in the rebuttals below, this article’s authors don’t realize how counterintuitive complex systems can be.

Selected Quotations

- “We propose, instead [of Metcalfe’s square law], that the value of a network of size n grows in proportion to n log(n).”

- “The increasing value of a network as its size increases certainly lies somewhere between linear and exponential growth “

- “We admit that our n log(n) valuation of a communications network oversimplifies the complicated question of what creates value in a network… but it fits in with observed developments in the economy.”

- “The fundamental flaw underlying both Metcalfe’s and Reed’s laws is in the assignment of equal value to all connections or all groups.”

- “If Metcalfe’s Law were true, then two networks ought to interconnect regardless of their relative sizes. But in the real world of business and networks, only companies of roughly equal size are ever eager to interconnect.”

- “Zipf’s Law is one of those empirical rules that characterize a surprising range of real-world phenomena remarkably well. It says that if we order some large collection by size or popularity, the second element in the collection will be about half the measure of the first one, the third one will be about one-third the measure of the first one, and so on”

16. Metcalfe’s Law Recurses Down the Long Tail of Social Networking

Bob Metcalfe, 2006

Summary

Around 1980, Bob Metcalfe, the inventor of the Ethernet, noticed that the value of the Ethernet network grew with each new ethernet node added at an exponential rate, a discovery which was immortalized as Metcalfe’s Law by George Gilder in 1993. Years later, Metcalfe revisits his own Law after criticism (above). First, Metcalfe proceeds to (hilariously) debunk Olydzko & co’s attempt to refute and revise his law, and then he goes on to suggest areas for further refinement. In doing so, he adds context and depth to his formulation of the value of network effects.

Why It Matters

There are quite a few key insights for Founders in Metcalfe’s essay, many of which were highly prescient given when it was written. Firstly, he anticipates the phenomenon of negative network effects long before social networks like Facebook began to experience it — and modeled mathematically how the “diseconomies of scale” of a network might begin to eventually overcome the increasing returns from positive network effects. He also inadvertently accounts for Reed’s Law (which would otherwise seem to contradict his law) by observing that Metcalfe’s Law recurses in local networks. That is to say, the value of the network like the internet, given by Metcalfe’s Law to be N^2, can be multiplied by the value of nested local networks (i.e. clusters), recursing all the way down the long tail of clusters within a network.

Selected Quotations

- “As I wrote a decade ago, Metcalfe’s Law is a vision thing. It is applicable mostly to smaller networks approaching ‘critical mass.’ And it is undone numerically by the difficulty in quantifying concepts like ‘connected’ and ‘value.’”

- “There may be diseconomies of network scale that eventually drive values down with increasing size. So, if V=A*N^2, it could be that A (for “affinity,” value per connection) is also a function of N and heads down after some network size, overwhelming N^2.”

- “Also important would be linking Metcalfe’s Law to Moore’s Law and showing how that potent combination underlies what WIRED’s Editor-in-Chief Chris Anderson calls The Long Tail.”

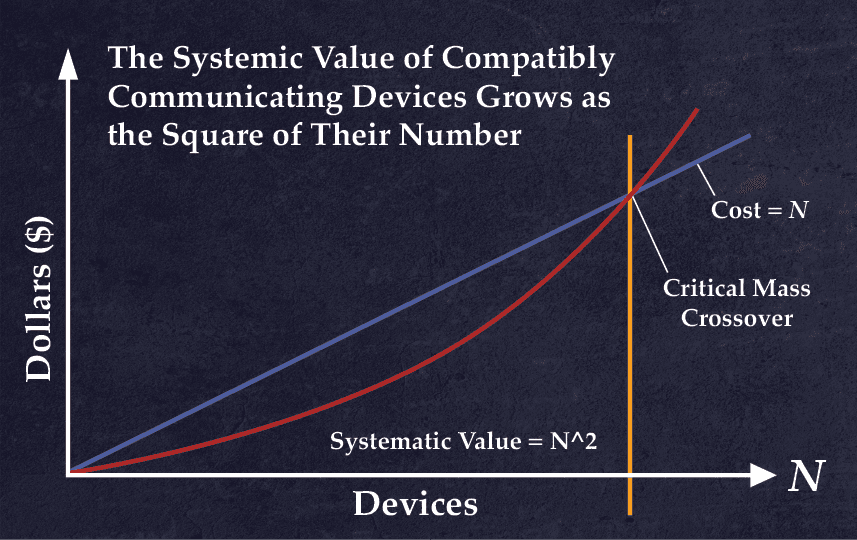

- “Metcalfe’s Law points to a critical mass of connectivity after which the benefits of a network grow larger than its costs. “

- “Combining Moore’s and Metcalfe’s Laws, therefore, the number of users at which a network’s value exceeds its cost halves every two years”

- “Looking more closely, I see that Metcalfe’s Law recurses. Just being on the Internet has some increasing value that may be described by my law. But then there’s the value of being in a particular social network through the Internet. It’s V~N^2 all over again.”

17. Metcalfe’s Law after 40 Years of the Ethernet

Bob Metcalfe, Computer, 2013

Summary

A follow-up to his 2006 refutation of what he now calls “Odlyzko’s Law”, e.g. the attempted revision of Metcalfe’s Law to define the value of a network as a logarithmic rather than exponential function of network size, this more formalized rebuttal uses a generalized sigmoid function based on Metcalfe’s Law (which Metcalfe calls a “netoid” function) to model an S-curve which he fits to Facebook data, plotting user growth data from 2004 to 2013 against Facebook’s annual revenue to show the first formal empirical proof of Metcalfe’s Law.

Why It Matters

Much of this article is aimed at formally proving the validity of Metcalfe’s Law, which is interesting of itself because it adds more weight to the importance of network effects for building transformative companies. But of particular interest are Metcalfe’s anecdotes about the growth of his ethernet company 3Com. Not only did he understand the value of network effects as the Marketing and Sales head of 3Com, but he actually used Metcalfe’s Law to sell his customers and motivate his salespeople. It’s a powerful example to Founders of how an understanding of network effects can help you sell your vision.

Selected Quotations

- “Critics have declared Metcalfe’s law, which states that the value of a network grows as the square of the number of its users, is a gross overestimation of the network effect, but nobody has tested the law with real data. Using a generalization of the sigmoid function called the netoid, Ethernet’s inventor and the law’s originator models Facebook user growth over the past decade and fits his law to the associated revenue.” – 26

- “Nobody (including me) has ever made the case for or against Metcalfe’s law with real data. “ – 26

- “I have modeled Facebook user growth over the last decade and fitted Metcalfe’s law to associated revenue, a surrogate of Facebook’s network value.” – 26

- “During a presentation to the 3Com sales force, I projected a 35-mm slide with the graph in Figure 2. I argued that if a network is too small, its cost exceeds its value; but if a network gets large enough to achieve critical mass, then the sky’s the limit” – 28

- “the 3Com sales force went back out into the field determined to get their customers’ Ethernets above critical mass, which we hoped to be about 30 nodes” – 28

- “Suspecting that not all network connections are of equal value and referring to Zipf’s law, Odlyzko and his colleagues countered—in what I will call Odlyzko’s law—that the growth in value of a network is approximately N × ln(N).” – 29

18. Data Network Effects In SaaS Enabled Marketplaces

Tomasz Tunguz, 2015

Summary

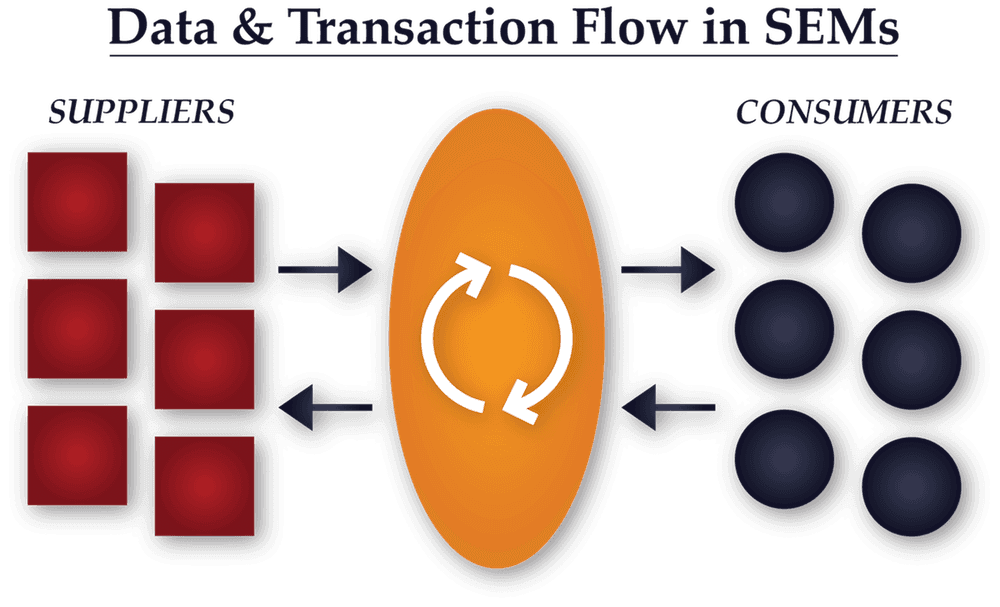

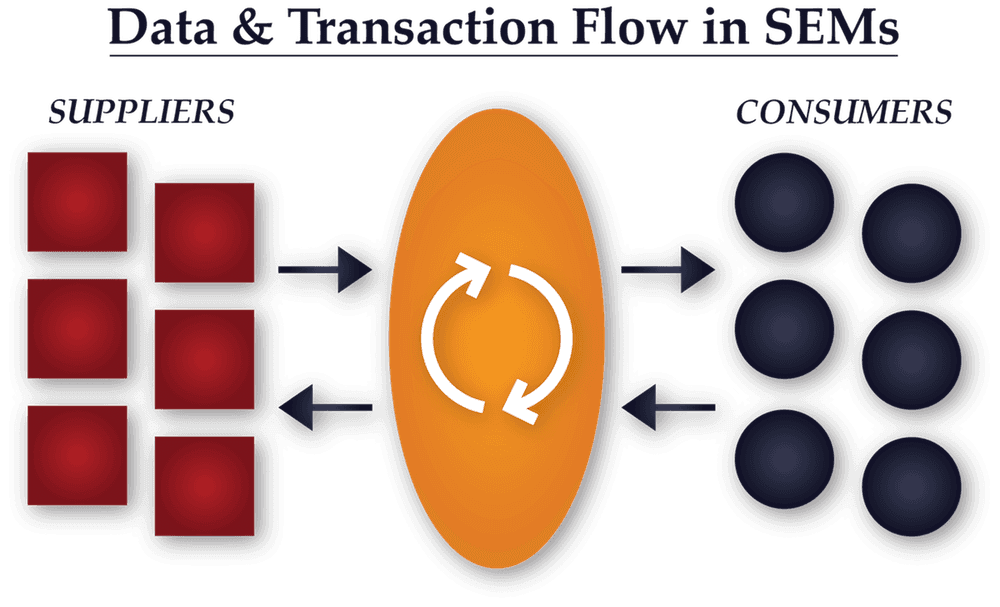

In this blog post, venture capitalist Tomasz Tunguz describes four key advantages enjoyed by software-enabled marketplaces that allow them to collect a high volume of valuable data and get a data network effect going.

Why It Matters

Valuable insights for marketplace Founders on how best to leverage their data.

Selected Quotations

- “SaaS Enabled Marketplaces (SEM’s) benefit from a unique advantage in their go-to-market. They have a panoptic view of their market place [sic], which over time provides them an unassailable competitive advantage.”

- “SEMs provide software to suppliers and consumers, and then make a market between them.”

- “The first SEMs flourished in advertising. Google manages one of the world’s largest advertising market places.”

- “Because SEMs deploy SaaS to both the supply side and the demand side, these companies can develop an exceptional understanding of their market.”

- “SEMs understand the supply/demand curve at every second.”

- “SEMs understand the operational excellence of their suppliers…This data enables the marketplace to amass census scale data on supplier performance, granular to the type of service rendered. The SEM can better qualify and match supply and demand”

- “The accumulated data on both consumer demand and supplier performance compounds into a unique data asset that erects a moat around the business.”

19. A16z Podcast: Not all Network Effects Are Created Equal

With James Currier (Managing Partner, NFX) & Anu Hariharan

Summary

Network effects experts James Currier (Managing Partner, NFX) and Anu Hariharan (formerly a16z, now Partner @ Y Combinator) recap the history, evolution, and taxonomy of network effects.

Why It Matters

There are many gems here about the big network effects success stories, and interesting insights into why network effects are so powerful a defensibility for technology in particular. It’s also a good recap of network effects content found in the NFX Manual and NFX Bible, although in podcast form.

Selected Quotations

- “Network effects are the only defensibilities native to the Internet era and therefore they’re the most powerful” – James Currier

- “Facebook is not valuable if you’re the only user on the platform… compared to phones or ethernet. With a piece of hardware there was more friction to adopt the hardware.” – Anu Hariharan

- “Network effects are native to technology in the sense that the technology wants to connect. Every ethernet switch connects to every ethernet switch. Mobile devices connect to mobile devices. Ever since the 60s when we started using chips it was endemic to these technologies that they wanted to be connected, and once connected, they become networks.” – James Currier

- “Facebook might be around in 10 years or it might not be, but it’s pretty clear that messaging will be around” – James Currier

- “Not all marketplaces have network effects, but they all have potential [depending on their stage of development]” – Anu Hariharan

20. Strategies for Two-Sided Markets

Geoffrey Parker, Marshall W. Van Alstyne, and Thomas R. Eisenmann, Harvard Business Review, 2006

Summary

An analysis of two-sided networks focusing on how to navigate the complexity of multi-sidedness in the optimal way.

Why It Matters

Founders building 2-sided platforms, marketplaces, or any other business that have to handle supply and demand dynamics will find actionable tactics in this article.

Selected Quotations

- “Platforms catalyze a virtuous cycle: More demand from one user group spurs more from the other.” – pp.1

- “The key challenge? Get pricing right: ‘Subsidize’ one user group while charging the other a premium for access to the subsidized group. Adobe’s Acrobat PDF market comprises document readers and writers. Readers pay nothing for Acrobat software. Document producers, who prize this 500- million-strong audience, pay $299.” – pp. 1

- “If you seize a platform opportunity but don’t get it right the first time, someone else will.” – pp. 1

- Pricing strategies: “Subsidize quality- and price-sensitive users” or secure “marquee” users’ exclusive participation in your platform [i.e. provide reasons not to multi-tenant for the most important users]” – pp. 1

- “Products and services that bring together groups of users in two-sided networks are platforms. They provide infrastructure and rules that facilitate the two groups’ transactions and can take many guises” – pp. 3

- With two-sided network effects, the platform’s value to any given user largely depends on the number of users on the network’s other side” – pp. 3

21. Required reading for marketplace startups: The 20 best essays

Andrew Chen, published on Twitter

Summary

A great anthology resource on marketplaces from Andrew Chen, one of the most prolific writers on growth, formerly of Uber and currently a General Partner at Andreessen Horowitz.

Why It Matters

This is a great list of the best articles for Founders discussing real world, applied approaches to building marketplaces. It includes the NFX essay on Market Networks. Since Andrew published the list, NFX has subsequently published 19 Tactics to Solve the Chicken-or-Egg Problem and the NFX Marketplace Scorecard which we would also consider essential marketplace reading.

22. Pipes, Platforms, and the New Rules of Strategy

Marshall W. Van Alstyne, Geoffrey G. Parker, and Sangeet Paul Choudary, Harvard Business Review, 2016

Summary

This article introduces a more nuanced framework for understanding platforms, in which the authors propose 4 types of “players” in a platform ecosystem: owners (e.g. Google), providers (e.g. Samsung), producers (e.g. Android app developers), and consumers (e.g. Android phone consumers). It contrasts the “pipeline” business model that dominated traditional industries with the more dynamic platform model common in tech and shows how the rise of network effects has upended the old rules of strategy that used to apply in supply-side industrial economies.

Why It Matters

Van Alstyne et. al. make clear just how dominant network effects are as a defensibility in the digital age. As the authors point out, it took less than 8 years for Apple and Google to demolish the entrenched market positions of Nokia, Motorola, LG and other mobile manufacturers by leveraging a 2-sided platform network effect via iOS and Android. Brand and scale were not enough to defend against a powerful 2-sided network effect. Although the authors conflate platforms with all 2-sided networks, they get the essential point right by compellingly showing the hierarchy of defensibilities with examples and data.

Selected Quotations

- “In 2007 the five major mobile-phone manufacturers—Nokia, Samsung, Motorola, Sony Ericsson, and LG—collectively controlled 90% of the industry’s global profits. That year, Apple’s iPhone burst onto the scene and began gobbling up market share. By 2015 the iPhone singlehandedly generated 92% of global profits, while all but one of the former incumbents made no profit at all.”

- “Apple conceived the iPhone and its operating system as more than a product or a conduit for services. It imagined them as a way to connect participants in two-sided markets—app developers on one side and app users on the other—generating value for both groups. As the number of participants on each side grew, that value increased—a phenomenon called ‘network effects,’ which is central to platform strategy.”

- “Information technology has profoundly reduced the need to own physical infrastructure and assets. IT makes building and scaling up platforms vastly simpler and cheaper, [and] allows nearly frictionless participation that strengthens network effects”

- “Pipeline businesses create value by controlling a linear series of activities—the classic value-chain model. Inputs at one end of the chain (say, materials from suppliers) undergo a series of steps that transform them into an output that’s worth more: the finished product. “

- “The competitive forces described by Michael Porter… still apply. But on platforms these forces behave differently, and new factors come into play.”

- “The engine of the industrial economy was, and remains, supply-side economies of scale… The driving force behind the internet economy, conversely, is demand-side economies of scale, also known as network effects.”

- “The five forces model doesn’t factor in network effects and the value they create. It regards external forces as ‘depletive,’ or extracting value from a firm, and so argues for building barriers against them”

Part III: Other Defensibilities

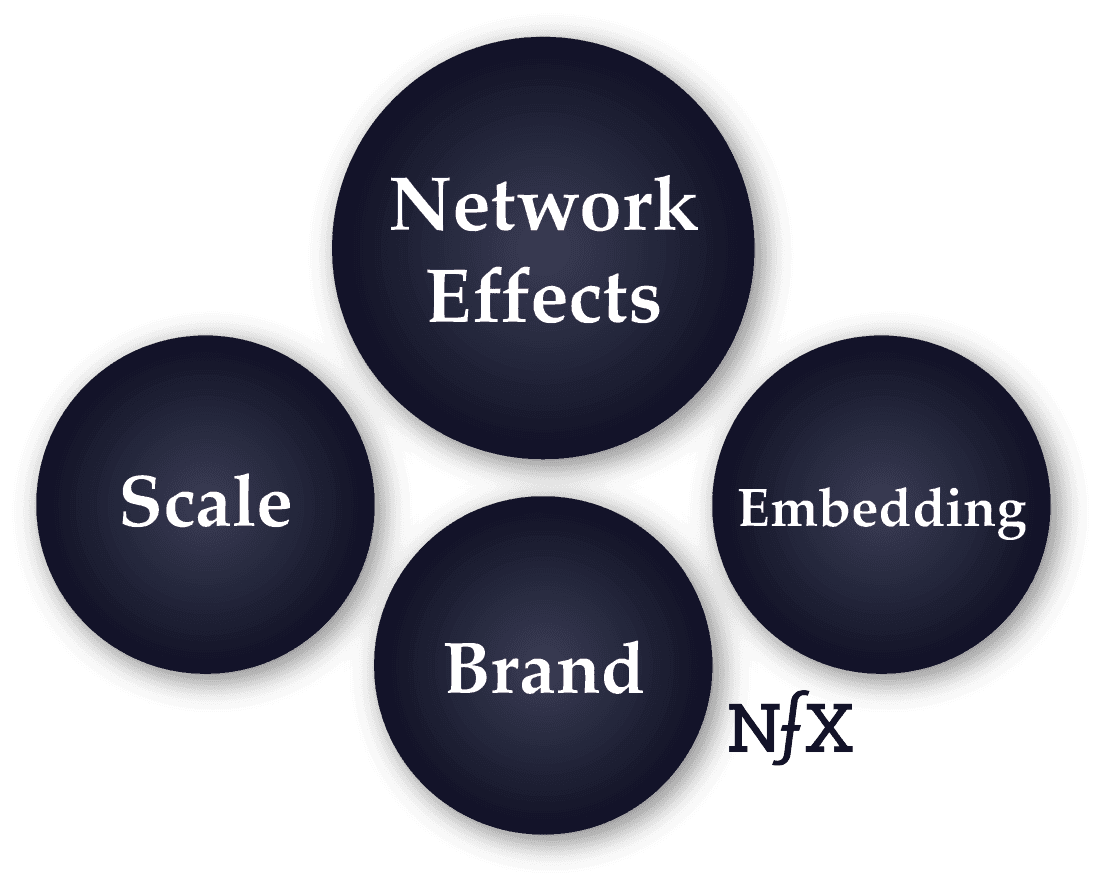

We believe that for startup Founders, network effects are the most important defensibilities because they are native to the internet and because of the evidence we see: network effects have accounted for 70% of all value created in tech since 1994.

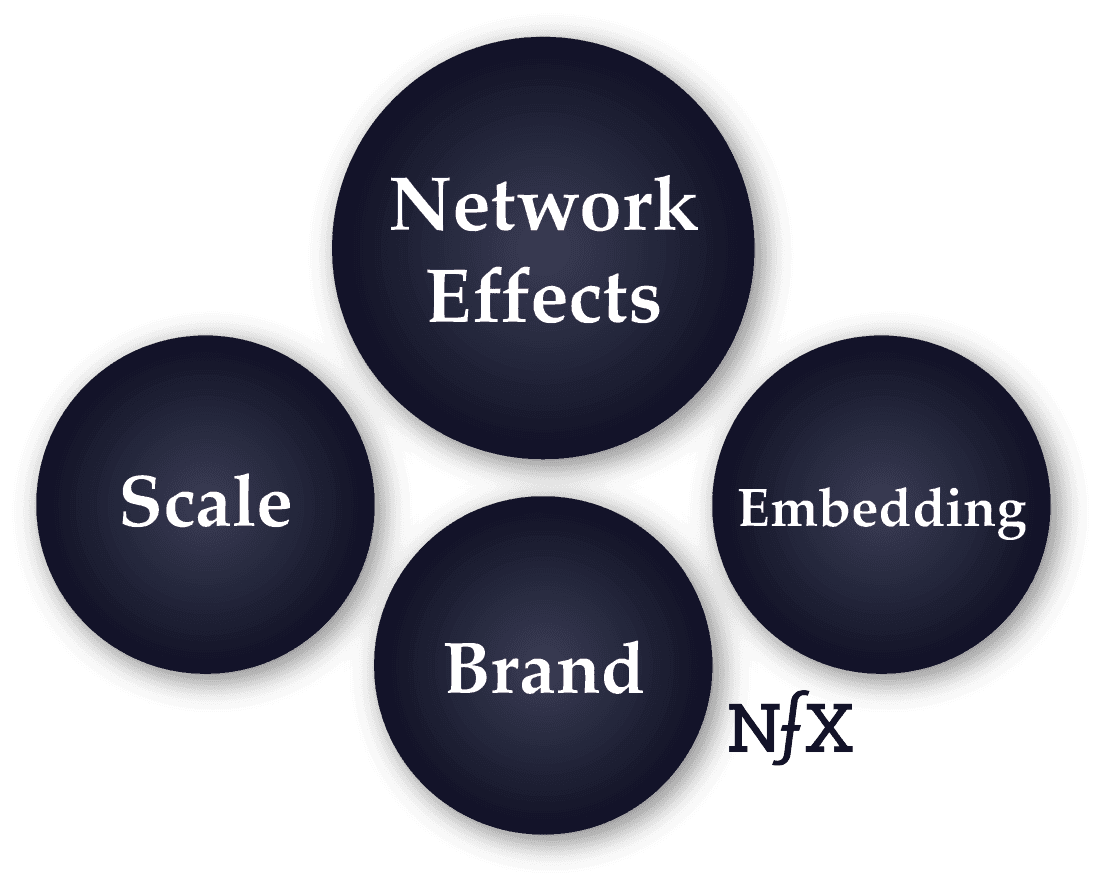

And in the digital world, there are three other defensibilities which also remain: brand, embedding, and scale. This section of the archive brings together sources written by investors from James Currier to Warren Buffet discussing the importance and nuances of defensibilities — a concept entrepreneurs must grasp to succeed in the digital world.

23. Defensibility Creates the Most Value For Founders

James Currier (Managing Partner, NFX), TechCrunch, 2015

Summary

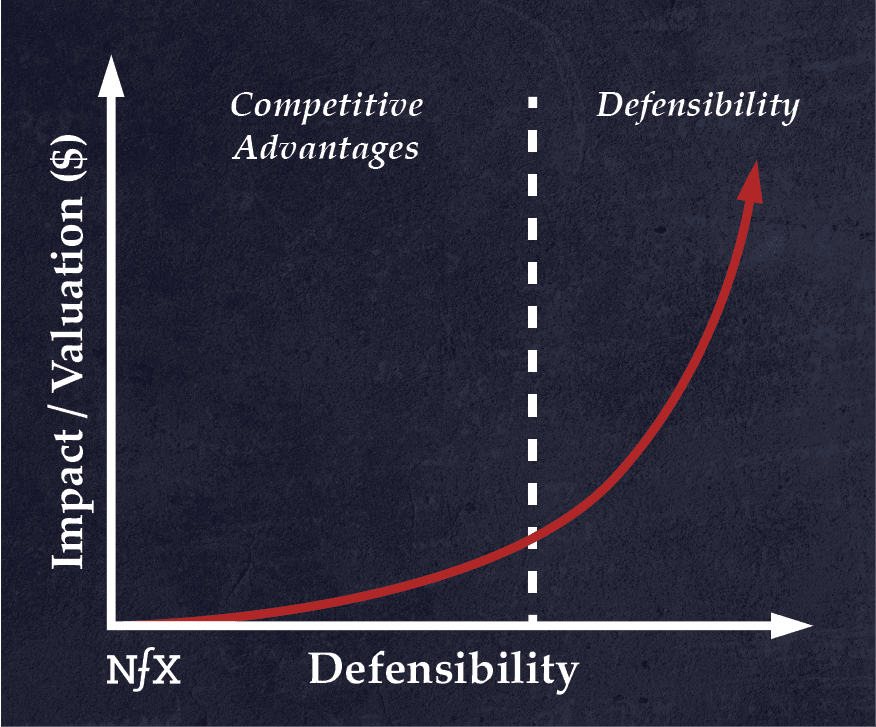

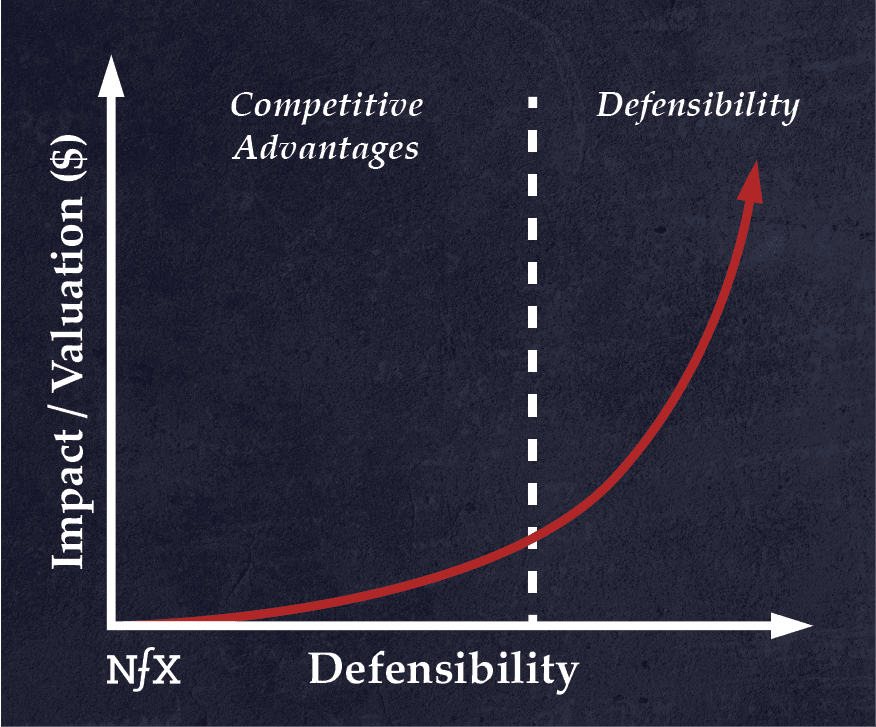

If you haven’t read NFX’s original essay on defensibility, it’s a good place to start. In it, we explain why defensibilities create the most valuable companies, and why competitive advantages (while necessary) can only get you so far. We also point out that old defensibilities — access to raw materials, location, regulation, etc— apply less in a digital context, leaving just four defensibilities in the digital age: network effects, scale, brand, and embedding.

Why It Matters

Founders who read this will immediately feel the necessity of having a defensibility strategy as soon as possible — the sooner, the better. Even Founders with a passing familiarity with the concepts will find it a worthwhile read. The discussion of the different competitive advantages, from speed to capital, can also help early-stage Founders decide where to focus their efforts.

Selected Quotations

- “If I have a choice, I’d rather start a business where I know if it works, it will be defensible… that I can really protect it from competition. For a long time.”

- “Nearly all of the massive returns to you and your investors — the 100X or 500X returns — come from businesses that have long-term defensibility.”

- “In the old days, the business literature listed many ways to create defensibility: unique access to raw materials, favorable geographic location, government regulations like tariffs, patents and licenses, etc.”

- “Network effects have emerged as the native defense in the digital world.”

- “‘Competitive advantages’ help your company become successful. ‘Defensibility’ helps you stay there.”

- Competitive advantages include: speed, capital, team quality, content, buzz, relationships, proximity to Silicon Valley, and patents.

- “If you build a business with good competitive advantages, your value grows linearly as you grow revenues.”

- “If you’re able to move past competitive advantages to true defensibility — to really being able to protect your business from competition — your value grows exponentially.”

24. Economics of the Moat and the Castle

Warren Buffett, Morning Session – 1995 meeting (section 25)

Summary

In this 1995 video-recorded conversation with Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett speaks about company defensibility. He coins the term “economic moats” in referring to a business’s defensibilities, and explains how he sees defensibility as the fundamental “secret” to a company’s success.

Why It Matters

This is an interesting early formulation of defensibility theory by one of the world’s most influential and successful investors, which paved the way for how people would think about defensibility and its importance for years to come.

Selected Quotations

- Q: “what are the fundamental rules of economics you used to make money for Berkshire?” A: “ the most important thing you can — you know, what we’re trying to do is we’re trying to find a business with a wide and long-lasting moat around it… And in essence, that’s what business is all about.”

- “What we’re trying to find is a business that, for one reason or another — it can be because it’s the low-cost producer in some area… it could be because of its position in the consumers’ mind [i.e. brand], it can be because of a technological advantage, or any kind of reason at all, that it has this moat around it.”

- “all moats are subject to attack in a capitalistic system, so everybody is going to try and … figure out how to get to it.”

25. How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy

Michael E. Porter, Harvard Business Review, 1979

Summary

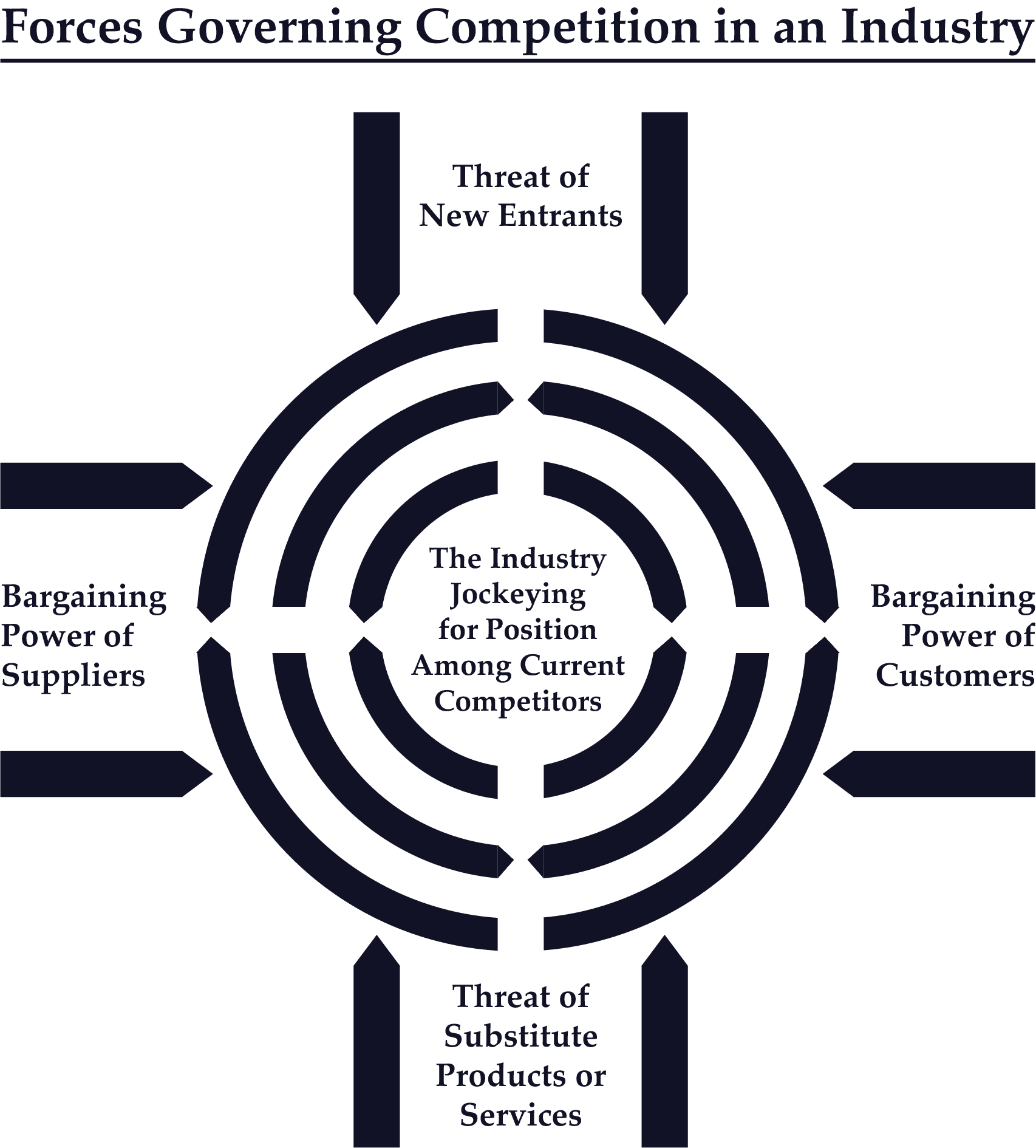

This influential essay, commonly known as the “Five Forces Model,” outlines the various competitive forces that shape different industries, and relates those forces to the potential profitability of companies operating in markets. Porter classifies competitive forces into 5 broad camps: the threat of new entrants, bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of customers, threat of substitute products/services, and internal competition (“jockeying for position among current competitors”).

Why It Matters

This article provides insight into the relationship between company defensibility and profitability within the larger ecosystem of an industry. It also accurately identifies two of the defensibilities that would persist into the internet age: scale and brand. However, because it was written before the advent of the internet economy, the five forces model doesn’t sufficiently take network effects into account. Later, work from other HBS professors would update this perspective — see the Pipes to Platforms model (Van Alstyne, Parker, and Choudary, 2016).

Selected Quotations

- “The essence of strategy formulation is coping with competition.”

- “Intense competition in an industry is neither coincidence nor bad luck.”

- “In the fight for market share, competition is not manifested only in the other players. Rather, competition in an industry is rooted in its underlying economics.”

- “The state of competition in an industry depends on five basic forces… The collective strength of these forces determines the ultimate profit potential of an industry.”

- “Whatever their collective strength, the corporate strategist’s goal is to find a position in the industry where his or her company can best defend itself against these forces or can influence them in its favor”

- “Every industry has an underlying structure, or a set of fundamental economic and technical characteristics, that gives rise to these competitive forces.”

- “The seriousness of the threat of entry depends on the barriers present and on the reaction from existing competitors that entrants can expect.”

26. All Revenue is Not Created Equal

Bill Gurley, Above the Crowd, 2011

Summary

In this classic essay, Bill Gurley discusses the various factors that contribute to how companies are valued against their revenue, or their “price/revenue” multiple. He provides a scorecard of 10 business characteristics that impact a company’s likelihood of making it into what he calls the “10x+ price/revenue multiple club”. He includes 3 of the 4 defensibilities — network effects, embedding, and scale — in his scorecard, and also points out that, of these, network effects are the most powerful.

Why It Matters

Founders looking to understand how investors value companies and what draws their interest should give this essay a thorough read. It’s an excellent framework and comes from one of the best in the business. Beyond explaining nuances of different defensibilities (what Bill Gurley calls “competitive advantages”), it also contains pragmatic nuggets about what to watch out for in terms of customer behavior, market fragmentation, gross margin, and predictability of forward revenue if you’re looking to build a valuable company.

Selected Quotations

- “By far, the most critical characteristic that separates high multiple companies from low multiple companies is competitive advantage…How easy is it for someone else to provide the same product or service that you provide?”

- “If high price/revenue multiple companies have wide moats or strong barriers to entry, then the opposite is also true. Companies with little to no competitive advantage, or companies with relatively low barriers to entry, will struggle to maintain above-average price/revenue multiples”

- “No discussion of competitive advantages and barriers to entry is complete without a nod to perhaps the strongest economic moat of all, network effects.”

- “Second, networks effects are discussed way more than they exist. Many things people identify as network effects are merely economies of scale, which are not nearly as powerful.“

- SaaS are favored “for the same reason that investors favor companies with sustainable competitive advantages, investors favor pricing models that provide a high level of predictability and consistency in the future.” e.g. embedding

- “Investors love companies with scale. What this means is that investors love companies where, all things being equal, higher revenues create higher profit margins.”

- “In order to measure how a business is scaling, many investors look at marginal incremental profitability.”

- “you would rather have a highly fragmented customer base versus a highly concentrated one… You also have an obvious issue if your top 2-5 customers can organize against you. This will severely limit pricing power. “

27. Reinforcement: The Hidden Key to Building Iconic Tech Companies

James Currier (Managing Partner, NFX), 2018

Summary

Expanding on our previous writing on defensibility and network effects, we explore the concept of reinforcement, i.e., the network effects of defensibilities. The observation at the heart of reinforcement is that the more defensibilities you add to your company, the more powerful all your other defensibilities become — just as the different parts of a castle work to reinforce one another, making the whole much more formidable than the sum of its parts.

Why It Matters

One of the key observations of this essay for Founders is that companies with core network effects are the easiest to reinforce. That is, they are typically the quickest to start benefiting from the compounding returns of multiple defensibities. We also discuss how companies like Amazon, Uber, and Facebook — all of which have multiple defensibilities — made an intentional effort to keep layering on more defensibilities throughout their lifespan.

Selected Quotations

- “Every iconic company to come out of Silicon Valley in the last 25 years has done the same three things: product-market fit, rapid growth, and reinforcement.”

- “The sooner a company starts to reinforce, the greater its chances of success.”

- “whenever a company adds a new defensibility… its existing defensibilities become even more powerful.”

- “Any type of defensibility will have a reinforcement effect on all the others, but network effects have the most dramatic impact. This is why companies that start out with core network effects — network effects that are integral to a company’s core business, not arising from features added later — are the easiest to reinforce. It’s also why we think of reinforcement as the network effect of network effects.”

- “Though it may seem like a product of luck from the outside, reinforcement requires deliberate effort.”

28. The Dentist Office Software Story

Fred Wilson, AVC, 2014

Summary

A fictional but revealing anecdote by venture capitalist Fred Wilson that brings home how lethal it is for Founders not to have a defensibility strategy, and how almost any tech product can become a commodity over time if not properly defended.

Why It Matters

Fred Wilson says that he realized early on that he didn’t want to invest in commodity software, and so he asked himself “what will provide defensibility” for the software he chose to invest in? He concluded, correctly, that networked products are the least vulnerable to commoditization and therefore the most worthy of investment. Fred is also shrewd here in pointing out that network effects apply to enterprise products as well as consumer products.

Selected Quotations

- “This story is designed to illustrate the fact that software alone is a commodity. There is nothing stopping anyone from copying the feature set, making it better, cheaper, and faster.”

- “We asked ourselves, ‘what will provide defensibility’ and the answer we came to was networks of users, transactions, or data inside the software.”

- “We felt that if an entrepreneur could include something other than features and functions in their software, something that was not a commodity, then their software would be more defensible.”

- “That led us to social media, to Delicious, Tumblr, and Twitter. And marketplaces like Etsy, Lending Club, and Kickstarter. And enterprise oriented networks like Workmarket, C2FO, and SiftScience.”

29. Amazon Go and the Future

Ben Thompson, Stratechery, 2018

Summary

Scale, as a function of spreading fixed costs and low marginal costs, is a basic concept from the industrial era — but it still applies to tech companies, which benefit from the very low marginal cost of software. Using Amazon as a case study, in this essay Stratechery’s Ben Thompson explores the mechanics of scale effects, providing a simplified, basic, and current description of how scale defensibility works.

Why It’s Relevant

This essay explains the unique scale advantages enjoyed by tech companies, and the exact reasons why scale can be such an effective defensibility. Thompson shows that, especially with tech, low marginal costs mean that margins actually scale along with revenue — so that an incumbent with scale effects enjoys much more profitability than new entrants.

Selected Quotations

- “To understand the economics of tech companies one must understand the difference between fixed and marginal costs”

- Marginal costs: “costs increase in line with revenue. Fixed costs, on the other hand, have no relation to revenue.”

- “R&D is so important to tech company profitability: while digital infrastructure obviously needs to be maintained, by-and-large the investment reaps dividends far longer than the purchase of any physical good. “

- “A huge amount of fixed costs up front is overwhelmed by the ongoing ability to make money at scale; to put it another way, tech companies combine fixed costs with marginal revenue opportunities, such that they make more money on additional customers without any corresponding rise in costs.”

- “the economics of software: massive fixed costs, and effectively zero marginal costs”

- “network effects, supercharged by the ability to scale for free, are these companies’ moats.”

- “Technology like Amazon Go is the ultimate expression of capital: invest massive amounts of money up front in order to reap effectively free returns at scale”

30. The Scale of Tech Winners

Benedict Evans, 2017

Summary

This article discusses scale in the context of modern tech giants like Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple. It explains how scale has enabled them to build secondary competitive advantages, such as the ability to conduct large experimental projects “without betting the company” — an important moat because it allows these companies “to disrupt themselves”.

Why It Matters

The relative decline of the once dominant Microsoft after the 1990s and the even more precipitous declines of AOL, Myspace, and Yahoo show that even companies with strong scale and network effects are still vulnerable to new waves of technology which allow them to be disrupted. Benedict Evans’ analysis is important in showing how companies can leverage existing competitive advantages to anticipate future threats — and how defensibilities, if married to the proper strategy, can endure the threat of disruption.

Selected Quotations

- “Google, Apple, Facebook & Amazon (GAFA) are 3x the scale of Wintel [Windows + Intel combined]… They have far more employees, and they invest far more.”

- “Being a big tech company means something different now to in the past.”

- “Scale means these companies can do a lot more. They can make smart speakers and watches and VR and glasses, they can commission their own microchips, and they can think about upending the $1.2tr car industry.”

- “If you’re riding the smartphone supply chain cornucopia but can’t construct a story further up the stack, around cloud, software, ecosystem or network effects, you’re just another commodity widget maker.”

- “The shift to mobile was a fundamental structural threat that unbundled Facebook – the founder spent over 10% of the company to buy the most successful unbundlers and, as importantly, didn’t smother them after he’d bought them”

- “‘Disruption’ doesn’t work if everyone’s read the book, and everyone has. This, to repeat, is compounded by scale”

- “the new platforms have created unprecedented opportunities – 3bn smartphone users today are an unprecedented ‘white space’ for company creation. But they often expand into that space themselves.”

31. Beyond Network Effects: Digging Moats in Non-Networked Products

Matt Heiman, Greylock, 2018

Summary

In this article, CRV investor Matt Heiman discusses each of the three non-network effects defensibilities — scale, brand, and embedding (he bundles embedding under “switching costs”). The article walks through the nuances of defensibility for non-networked products.

Why It Matters

Heiman breaks down three reasons why scale makes companies more defensible: negotiating leverage, amortization of fixed assets, and product density. He also thinks that brand has become even more important in the digital age because the internet “elevates the importance of trust”. What’s more, his analysis of embedding is spot on — he points out that an embedding strategy is typical of enterprise software products like Salesforce. SaaS business models often rely on embedding themselves into customer operations and incur high switching costs, making it hard for competitors to gain market share.

Selected Quotations

- “Virtually all startup pitches include a conversation about competitive advantage or “moats,” and rightfully so; these moats are what ultimately allow companies to become compounding franchises and accrue outsized profits over the long run.”

- “If a startup can architect network effects into the product or business model, that is worth its weight in gold”

- “However, there are real world problems to be solved and businesses to solve them which… will not be candidates for a network effect approach.”

- “the internet magnifies the importance of scale effects in many ways; most obviously by removing the constraint of geography and reducing the capital intensity of growth.”

- “Economies of scale do not affect all industries equally. In fact, some industries exhibit dis-economies of scale”

- “Brand is one of the longest standing sources of defensibility. I believe that the internet has increased, rather than decreased, the importance of brand.”

- “some of the most successful startups have focused on creating a brand in a category where there was previously none.”

- “Switching costs is the one-time inconvenience or expense a user incurs to change over from one product to another”

- “Products that are used with high frequency tend to exhibit habit formation and once habit is formed, users are reluctant to switch.“

- “This is a phenomenon whereby a product becomes integrated with a user’s other products and workflow. This type of moat is most often seen in enterprise software products; many enterprise software giants get their defensibility from high switching costs”

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.