We don’t think most people really understand Facebook yet.

The recent round of negative press seems to indicate a surface-level understanding of the company. It’s important to look beneath the surface and examine the underlying laws of nature and physics that make Facebook tick.

In short, Facebook stands alone in the depth and variety of network effects they’ve built, even though most go undetected. As a result, their defensibility is unparalleled.

The network effect visible to most is many-to-many personal direct nfx. This is the core of what enabled Facebook to build a completely new type of media company. However, there’s more to it than meets the eye.

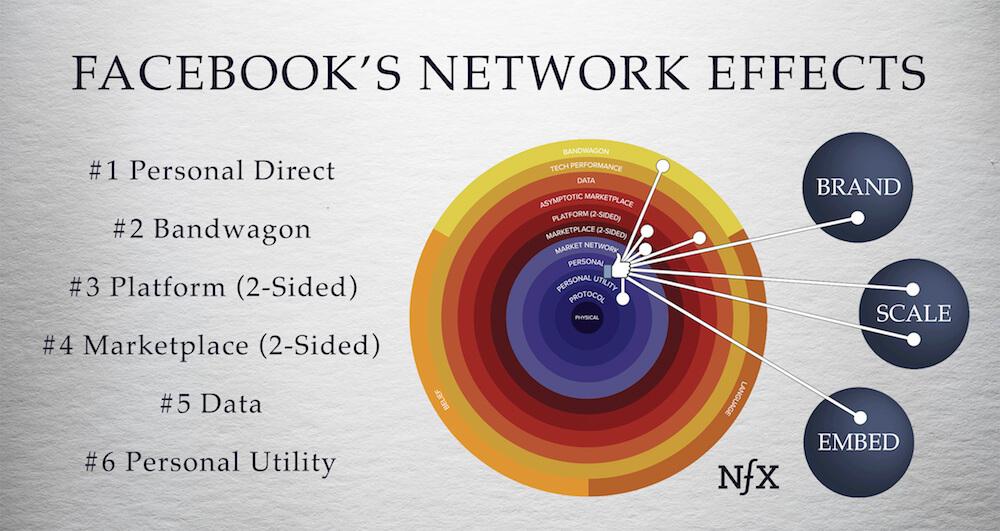

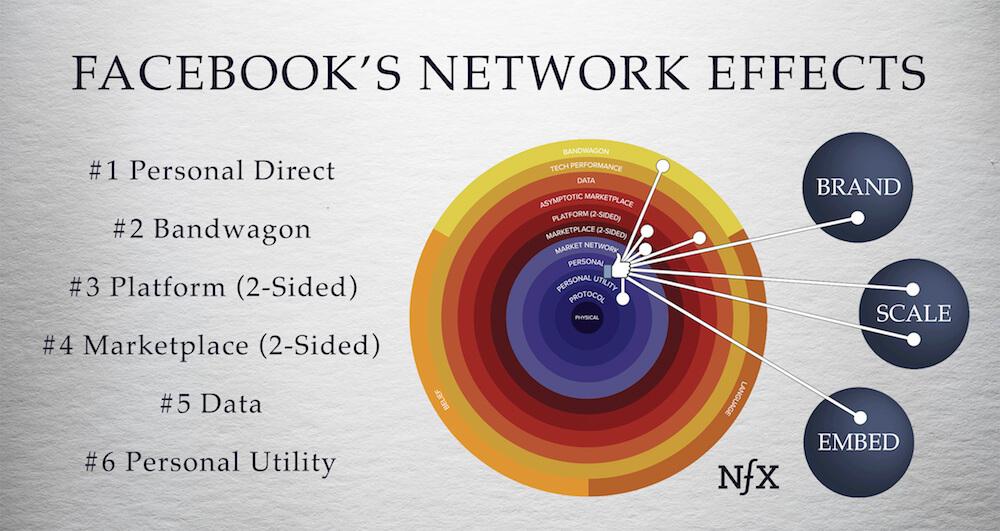

To date, we’ve actually identified that Facebook has built no less than six of the thirteen known network effects to create defensibility and value, like a castle with six concentric layers of walls. Facebook’s walls grow higher all the time, and on top of them Facebook has fortified itself with all three of the other known defensibilities in the internet age: brand, scale, and embedding.

Facebook represents a completely new type of media company. All media companies that came before — newspaper, radio, and television companies — were one-to-many, two-sided marketplaces with much weaker network effects. They were also less capable of building more network effects and other forms of defensibility on top of their existing products.

Simply put, we don’t believe the world has ever seen a network effect media company that equals Facebook’s defensibility and size. And it’s clear that both Facebook leadership and the rest of the world are just beginning to grapple with what that might mean for society.

Threats to Facebook do exist, in particular, government regulation and negative network effects. But it’s unclear whether they are serious enough to reverse Facebook’s mounting dominance.

Let’s break it down.

Personal Direct: network effect #1

When Mark Zuckerberg launched Facebook (a version of Friendster for the college crowd using real-name identity) from a Harvard dorm room in 2004, he unleashed a powerful many-to-many personal direct network effect. Like LinkedIn, which launched 2 years before it, Facebook tapped into people’s strong innate drive to maintain and project their personal reputation, identity, and network of friends and acquaintances. The more people used Facebook, the more valuable the network became for each person using it — and the less they would be willing to defect to another network where they would have to create a new friend graph from scratch.

Bandwagon: network effect #2

As Facebook spread through the North American university system, they picked up a bandwagon network effect, which is characterized by people’s fear of being left out. This in-group dynamic makes Facebook even more psychologically valuable to people and makes it less likely they would use another network.

Adding all 3 of the other defensibilities

Scale defensibility

Propelled forward in these early days by two powerful network effects, Facebook was able to start capturing another defensibility: Scale. While not a network effect, the scale effects that Facebook acquired made them more appealing, especially compared to potential competitors like InCircle at Stanford. This also served to enhance Facebook’s existing network effect defensibilities.

Brand defensibility

Soon, Facebook’s growing scale and phenomenal user engagement began to attract serious media attention. In 2005 and 2006 they were covered in major newspapers like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. Facebook quickly became a recognizable character in the cultural landscape, one with a myth-like origin story in a Harvard dorm room and a self-proclaimed manifest destiny to “make the world more open and connected.” As this narrative spread, it fueled their brand defensibility and helped set them further apart from their competitors such as MySpace.

Embedding defensibility

After attracting tens of millions users who had signed up to Facebook using their real names, Facebook grabbed the next defensibility, embedding, by launching “Facebook Connect” in 2008. This tool let millions of websites install code which allowed users to sign in to their sites with their Facebook logins. Facebook Connect was predicated on the idea that people were more likely to trust the Facebook brand than that of a smaller, lesser-known third-party service — and were more likely to sign up if they didn’t have to register yet another username and password.

It worked. Your Facebook login no longer just represented access to Facebook, it now also provided access to your WSJ subscription, your Spotify account, Etsy, FitBit, Yelp, and countless other widely-used sites and apps.

The login tool proved to be a win-win for both Facebook and the sites that implemented it. Third-party sites benefited because it lowered friction in their user onboarding experience, and Facebook benefited by embedding itself throughout the Internet ecosystem, building yet another web of defensibility.

Network effects as a strategy

Three years after launching Facebook, Zuckerberg seems to have had studied his own success and began to understand what drove it, saying in 2007 that

“I think that network effects shouldn’t be underestimated with what we do.” – Mark Zuckerberg, 2007

At this point, he and the Facebook team began adding network effect defensibilities, one by one, on top of their existing ones.

2-Sided Platform: network effect #3

Zuckerberg’s next move was to take a page from one of Silicon Valley’s most successful network effects companies — Microsoft and their platform network effect. It works by allowing software developers to publish on top of Microsoft’s software platform to reach the many users of the Microsoft operating system.

Facebook emulated Microsoft by launching Facebook Platform in 2007, which invited developers to build their Web applications on Facebook’s social graph and user data.

The Facebook Platform had millions of developers building apps on it, and along with iOS, underpinned the Cambrian explosion of consumer software innovation and experimentation that started in 2008.

Facebook’s platform push didn’t last for a few reasons:

- The apps tended mostly to be games

- Many apps were highly manipulative of users which ended up conflicting with Facebook’s own goals for its product.

- Compared to other two-sided platforms like Android, iOS, and Windows, the Facebook Platform wasn’t tied to any hardware devices. Users weren’t forced to use it to operate their latest tech gadget, weakening the demand side of the platform.

Despite not being particularly active today, the Facebook Platform was a strong attempt to garner a powerful two-sided network effect. It’s a great example of the experimental culture that, along with its network effects, makes Facebook so formidable.

2-Sided Marketplace: network effect #4

At the same time as the Facebook Platform, Facebook was also launching their self-serve ad platform, giving them access to a two-sided media marketplace network effect. The two sides of this marketplace consist of Facebook users (supply side) and advertisers (demand side). Just as Google and Craigslist found before them, the launch of Facebook’s self-serve advertising became a significant competitive advantage to attract the demand side and keep them coming back. Facebook now accounts for nearly a quarter of all online advertising revenue in the US.

Data: network effect #5

As Facebook grew and time spent on site expanded to its current average of about 41 minutes per day, Facebook evolved three different data network effects that make them even harder to compete with:

- Breadth of content inventory: As Facebook usage grew, users added more content (data) for Facebook to show to other users in the News Feed. This meant that the Facebook algorithm had more choices in curating users’ content feeds, increasing the product’s value to each user.

- Engagement data: the more people liked and commented on their friends’ posts, the more valuable posts became. Engagements from friends added to the value of information contained in each piece of content.

- Real-time behavioral data: Once Facebook user activity crossed a certain threshold, Facebook could start using behavior signals in real time to determine what users valued at any minute. That real-time data network effect is powerful and rare, a bit like Waze’s, where the data needs to be refreshed every minute to be valuable.

Personal utility: network effect #6

With the launch of Facebook messenger in 2011, Facebook went after yet another network effect — personal utility. Messenger originally began as a real-time chat feature inside the Facebook product before emerging as a new interface and a network unto itself.

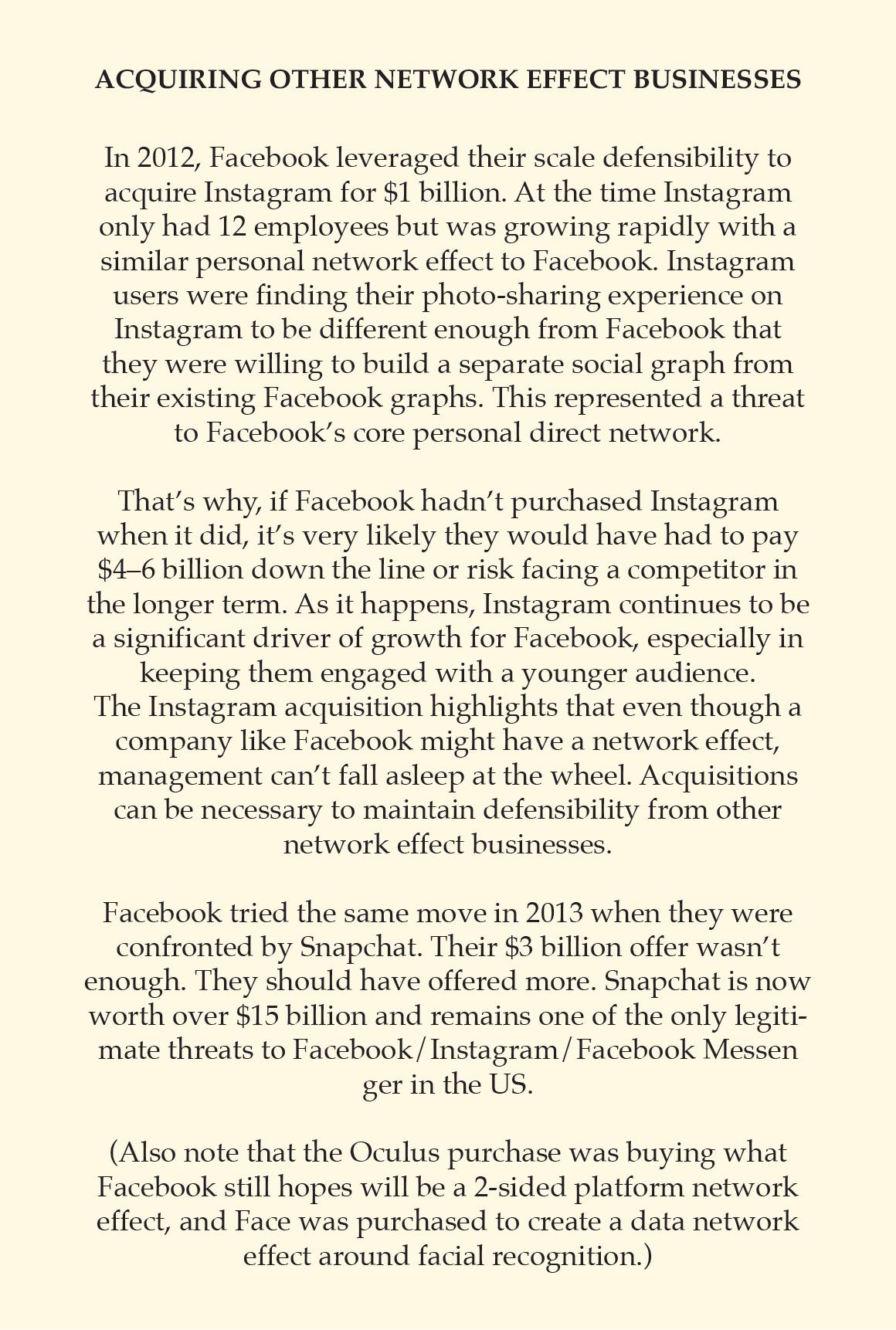

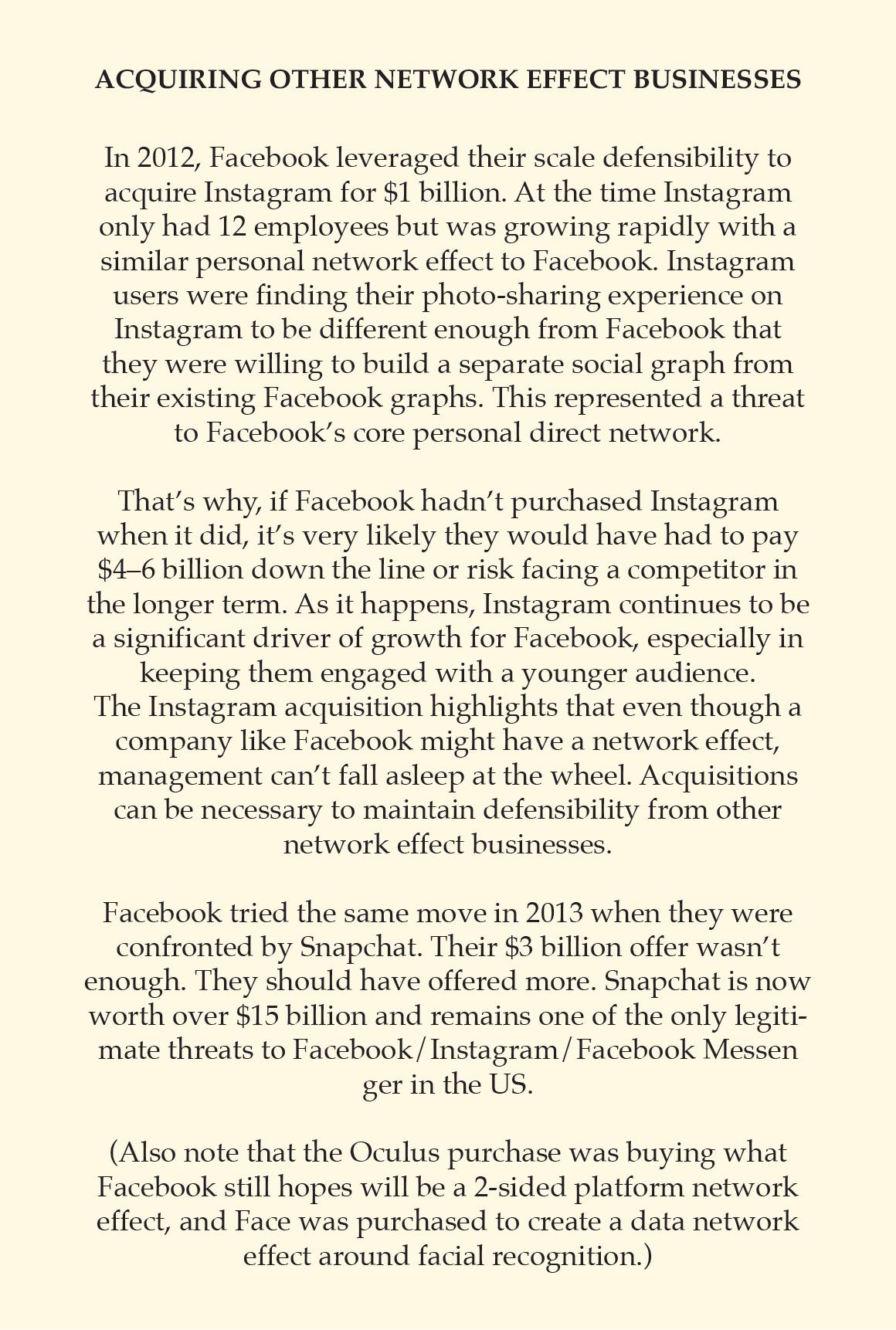

Facebook didn’t give Facebook Messenger a significant amount of attention until perhaps 2013, when leadership took notice of WhatsApp and their personal utility network effect. To keep WhatsApp from getting past them, Facebook was willing to pay whatever it took — in this case $19 billion — which amounted to the biggest acquisition in Facebook’s history by far.

Noticing WhatsApp’s similarity to the Facebook Messenger interface, Facebook decided to double down on its own native personal utility network. They invested heavily to get the best people in the business to come run Facebook Messenger. This included NFX co-founder and advisor, Stan Chudnovsky, as well as NFX investor David Marcus, who was CEO of PayPal (a company with 14,000 employees) when Facebook recruited him to be the Product Leader for Messenger. Under Stan and David’s stewardship, Facebook Messenger has grown from 100 million to 1.3 billion users in 3 years, cementing Facebook’s personal utility network effect.

The strategy Facebook has employed with Messenger — seeding and growing a second network effect business on top of an existing one — is one that has worked multiple times for Facebook in the past. We can expect it will continue to work.

Two-sided marketplace: network effect #4 (again)

In 2016, Facebook re-launched Facebook Marketplace, an online classifieds feature which they had tried unsuccessfully several times before. This time it seems to have gained some real traction, with more than 700 million monthly active users as of March 2018.

Craigslist, which is the marketplace Facebook is seeking to displace, is one of the oldest and most successful examples of an online two-sided marketplace. Founded in 1995, Craiglist was credited with killing newspaper’s most lucrative revenue stream, classifieds, by putting them online for free at Craigslist.org. Now Craigslist’s 23-year-old network effect is itself in danger of displacement by Facebook.

This is because Facebook has access to a much larger network of users who visit facebook.com with far greater regularity than Craigslist users visit their website. Facebook users also use real-name identities, which facilitates greater trust in transactions than anonymous Craigslist with its notoriously common scams. Ownership of classifieds would give them a second two-sided marketplace network effect and would further bolster Facebook’s defensibility.

Facebook’s future moves

As we’ve seen, Facebook can use its network effects, scale, brand, and embedding to launch other products to grab even more network effect businesses.

If we were them, reviewing their current assets and the list of the 13 network effects, we would be looking at:

- Payments. PayPal has a powerful direct network effect going with their payments network ($90 billion market cap), and Facebook could build something similar with their traffic and reach. Apple is trying to do the same with Apple Pay, as is Amazon with Prime.

- Giving Facebook Platform a second try. Facebook tried this first between 2007 and 2015, then essentially deprecated it. Facebook has been good at trying important network effect products repeatedly until they succeed, so they shouldn’t let their past failure deter them (they tried both Facebook Groups and Facebook Marketplace four times before they caught on). It’s still a good idea.

- Revamping identity management. Currently, we can log into millions of websites using our Facebook credentials. But other than that, the Facebook Identity system doesn’t do much. Facebook could cover a lot more territory if they turn the whole Internet into their own private mare nostrum, with Facebook at the center.

- Building a marketplace for SMB’s on top of Facebook pages. There are something like 70 million small businesses currently using Facebook pages, but they haven’t been given much to do other than collect likes. Where is the SMB network?

- Blockchain. Inherently, Blockchain technology uses network effects to create value. Telegram recently ICO’d with only 100M users on a mobile app. We expect more existing networks to issue tokens and to build out blockchain ecosystems. Facebook would be uniquely positioned to deploy something Ethereum-like here. Giving developers access to the billions of Facebook users would be good incentive to use Facebook blockchain as basis for their applications.

- Maintaining an aggressive acquisition strategy. Continue to acquire any network effect business that tries to get past them like Snapchat did or any business that could potentially lead to another technology platform, like Oculus.

Threats to Facebook

The major threat we see to Facebook is government action on one of three potential fronts.

- Privacy. Facebook knows a lot about its users. From the beginning, this has triggered privacy concerns because of their willingness to use and sell user data. With the EU’s new General Data Protection Regulation, the time might be upon us where Facebook will have regulatory headwinds. Even if there isn’t direct action against Facebook, the threat of action could lead Facebook to reduce its use of targeting data, reducing its revenues significantly.

- Public health. Research is increasingly measuring the addictive nature of Facebook and other social media, including its potential to induce depression and anxiety. If Facebook gets classified as something like tobacco, that would alter the playing field substantially.

- Antitrust. Antitrust action by the DoJ, such as that which Microsoft suffered in the late 1990s, could also significantly hamper Facebook’s momentum. Antitrust enforcement may even force Facebook to divest itself of acquisitions like Instagram and WhatsApp, although the Facebook network and product itself would be difficult to break up. Google was levied a $2.7 billion antitrust fine by the EU last year, and it’s conceivable that a public mood hostile to Facebook could motivate similar fines and penalties for Facebook.

Beyond regulation, another challenge Facebook faces is negative network effects. Negative network effects occur when the growth of a network actually decreases its value to existing users. Road networks are a classic example of networks suffering from negative network effects, since more drivers means more traffic and more pollution.

Facebook has recently begun to experience analogous pollution in its feed. Its algorithm is not always producing a great user experience, being, as it is, under attack by so much content straining to get attention.

Another source of negative network effects is simple pollution of the social graph. As users accumulate years of Facebook friendships, or as parents and work friends join and connect, social graphs becomes polluted with people they may not necessarily want to interact with. These negative network effects motivate a move to tighter or simply different networks — which is likely why teen usage of Instagram and Snapchat exceeds their use of Facebook.

The Power of Network Effects

To see clearly, we should understand the story of Facebook now and in the future as being more about the network mechanics and the physics of its defensibility than it is about temporary public sentiment. Looking beyond the surface, network effects are the core of that story for they are laws of nature.

As we’ve learned while building our own network effect startups, defensibility is the most important thing for Founders to create. Defensibility gives you time, capital and talent to fix things if they’re broken. It gives you room to evolve from a good leader to a great leader. Facebook’s meteoric rise demonstrates the value of network effects, which will be the force that paves their future.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.