Each year, the flu kills about 700,000 people globally. In the last decade, it’s killed millions. Yet our current annual vaccines (a $7B market) are often less than 50% effective at preventing infection.

If you ask the founder of Centivax, Jake Glanville, this status quo is insane.

That’s why a universal flu vaccine – which protects against all strains of the flu, past, present, and future – would be a category-defining technology. And that’s just one of the assets Centivax’s universal immunity platform is capable of developing. Their platform approach enables them to advance a growing pipeline that includes a pan-herpes Alzheimer’s preventative, a broad oncology treatment, a malaria vaccine, and a universal antivenom.

Today, Centivax hits a major milestone: the company has begun Phase 1a first-in-human trials of its universal flu vaccine in Australia – the first step in a broader Phase I program that will enroll roughly 300 healthy volunteers in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The trial will primarily assess safety and tolerability in humans, but the company should also collect data on the strength and breadth of the patients’ immune responses to a diverse panel of 24 strains, including currently circulating strains, guidance strains, pandemic strains, and historical strains.

It’s a major step towards demonstrating the world’s first universal vaccine response.

This moment is worth studying. Only a minority of biotech startups ever dose a first patient. Getting to the clinic requires not just breakthrough science but also operational excellence across manufacturing, regulatory affairs, clinical operations, and fundraising, all at once.

We sat down with Jake to unpack the strategy and decisions that took Centivax from lab to clinic. Below is a transcript of our interview, edited for clarity and concision.

If you’re looking for more on moving from idea to clinic, check out these resources:

- Why NFX Invested in Centivax

- Why Early Stage Companies Are Getting to Clinic Faster Than Ever

- How To Prove Your Bioplatform at Seed Stage

- Why Great Bioplatforms Always Win

NFX: So, Jake, you’re finally beginning first-in-human trials. How are you feeling?

I just gave a talk to my whole team last Friday, to prepare them: there’s this strange emotional thing that I’ve noticed often happens when people hold everything together while executing huge consequential marathon projects. What happens is that they hold the nerves together to reach the finish line, and then afterward, it all comes out. People say: “I just won the race, so why am I crying?”

I told them that this is normal, that they are champions, and to be forgiving of themselves and others. I’m waiting for the moment when I also go, “Oh my God – we did it.” It hasn’t hit yet.

Right now, people are overwhelmed, celebrating, and processing the emotions of the mad dash to get us into the clinic.

NFX: Getting into the clinic is this huge operational and emotional process. Walk us through that mad dash. How did you set yourself on this path?

So, we’ve been working on the technology for 13 years. It’s been a long build because it was a very novel approach compared to anything else out there. To get the world to see that we had to prove it out with overwhelming data from scratch.

It’s a fundamental shift in how vaccines are made, so we needed the world to see the receipts.

We tested over the years in a bunch of animals – pigs, mice, rats, ferrets, cows – and in human organoids. We iterated, and we optimized.

Our intention was always to build toward the clinic. But our vaccine didn’t just need to be universal and work against all the strains. It also had to be better than the current vaccines against the guidance strains those vaccines are designed to target.

It’s ironic because it’s already known that the guidance strains are typically multiple years old relative to the circulating strains. For example, if you just got a flu shot this winter, your “2025-2026” vaccine didn’t contain 2025-2026 circulating strains: it contained three guidance strains from 2021, 2022, and 2023. It’s never the case that a vaccine is an identical match to the year – it’s only a question of degree.

This year, the vaccines were a very batch-mismatched to the circulating Kappa “superflu.” That happens a lot. The current vaccines are often underwhelming. But we still have to beat them even against their own outdated and mismatched strains. Beat them on their home turf.

By 2024, we found we were already beating everything – including outperforming the commercial vaccines against their own guidance strains. So when you’re beating the old vaccines, even against their outdated strains, and importantly, you’re actually hitting all the circulating strains that actually get people sick…that’s how you know you could be sitting on a breakthrough and you’re ready for clinical development.

NFX: What happens next, once you realize that’s where you are?

At that point, a couple of things need to happen.

You need to manufacture it in accordance with GMP. This means you need to ensure it meets the quality and documentation standards suitable for human use. That’s very expensive and time-consuming. We spent over a year and an eye-watering amount of money on that, leveraging partner Contract Research Organizations (CROs).

Then there’s just a million other things, so it’s a full-court press on the team. You need to have these assays ready to go to characterize the release of that material. You need to submit very complicated applications to the regulatory authorities. We were submitting them to both the United States and Australia. We’re planning to run studies in both areas and also in the UK and the Netherlands. So that’s its own big massive mission.

You need to coordinate with the clinical sites, outline the tests you’ll be conducting, and establish timelines.

[Editor’s note: Centivax plans to run a Phase 1b trial in the northern hemisphere – the US and Europe – next summer, out of flu season. This is the best practice for Phase I testing of flu vaccines. It is currently summer in Australia, where the Phase 1a trial is running.]

And then, you know, you’re still a company. So you’re also fundraising during this period. Because, of course, if you don’t have money, you’re not going to execute in time.

It’s a battle of keeping all the timelines on track. And the classic thing, especially when you’re doing outsourcing or really anything involving science, is that there could be a technical delay. So you’re really staying on track and performing a lot of complicated, multidisciplinary team science. You have to get these different groups to coordinate to minimize or ideally avoid, up front, issues that could delay your clinical start date.

And we’ve managed to accomplish that.

NFX: How did you manage to keep all of that running smoothly and organized as a founder? Did you develop any systems to stay on track?

We knew we were heading here years ago once we figured out the technology was working. So I asked myself: what could kill a perfectly good project?

I saw this happen when I worked at Pfizer, and I’ve seen it at many other biotech clients across the industry. A perfectly good product can be buried by poor manufacturing, poor clinical design, or failure to fundraise. So I needed to fortify the team in those areas.

So, for clinical, we managed to get Jerry Sadoff to join as our Chief Medical Officer. This guy’s gotten more vaccines approved than anyone alive, including Gardasil, the shingles vaccine that was just shown to reduce Alzheimer’s risk, the COVID vaccine from J&J, and MMRV. You and I have taken his vaccines. So he left J&J to join our company and work on this universal flu program.

That was obviously transformative because he’s got battle scars that almost no one has. He knows how to avoid both common and rare problems, how to develop a sound clinical plan, and the tasks required to get there.

He brought in Shawna Cote as our Director of Clinical, who managed a huge number of clinical programs while at a CRO. So that covered clinical.

Then we reached out to Atsuko Sakurai-Sangria, our Director of CMC [chemistry, manufacturing, and controls]. She’s worked on the CMC of these vaccines for her last four jobs, so she is a unique boutique global expert in this space. Her arrival helped us sleep better at night.

We were also lucky to have Gus Zeiner join us as our Chief Innovation Officer. Back in my Distributed Bio days, Gus’s startup and my startup were neighbors in the JLabs incubator. He’s got the greatest technical mastery of molecular biology and bioengineering of anyone that I have ever met, and we had been wanting to work together for years.

The folks above fortified our founding team.

Stephanie Wisner is one of our founders. She previously worked at ARCH Venture Partners and authored the book Building Backwards to Biotech. She’s been essential during fundraising, scaling, and governance.

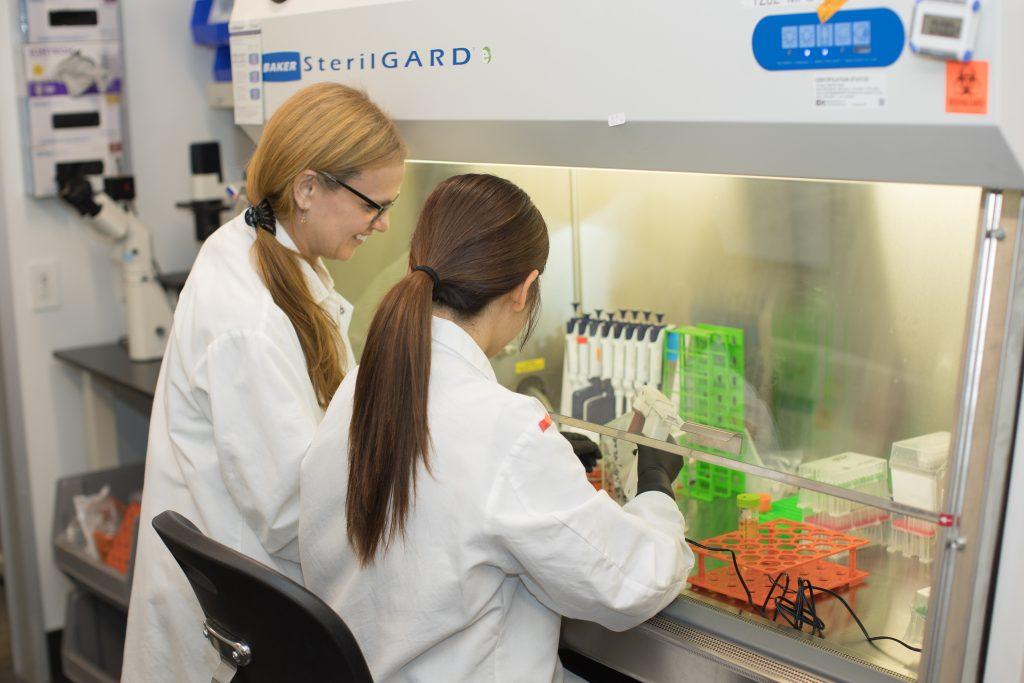

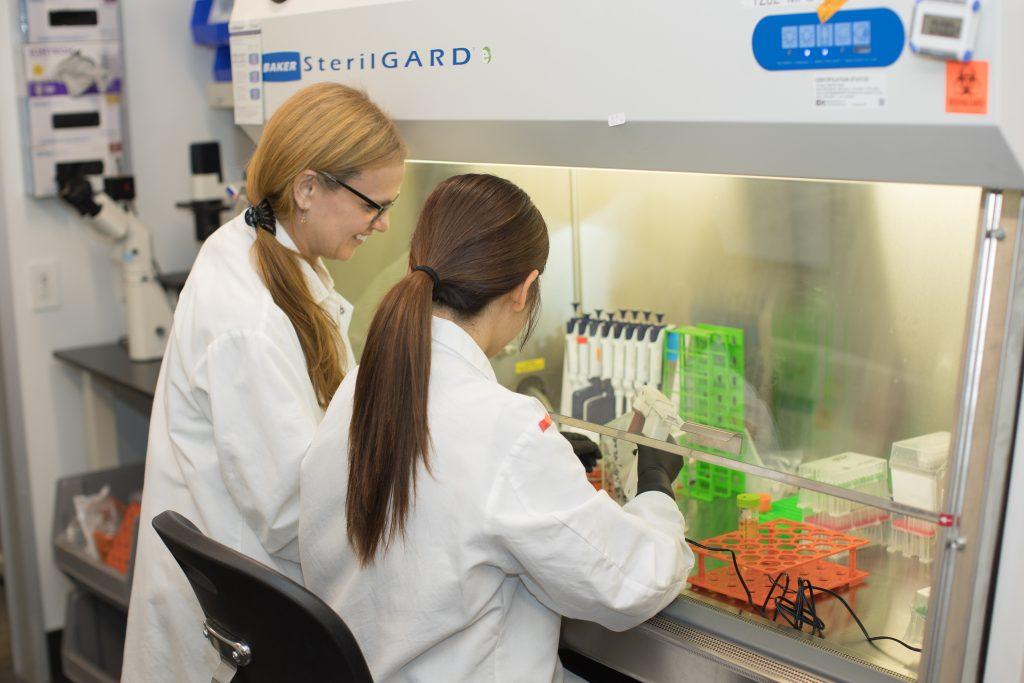

Another co-founder, our chief science officer, Sawsan Youssef, has enabled a bunch of the release assays and immunoassays as well as oversaw the immunology, the regulatory submissions, and myriad other areas of the company. She and I worked together at my last company, exited together, and before that, worked at Pfizer together. We’ve built technologies and exited companies for the past 18 years. The Pfizer drug sasanlimab is literally named after her for her outsized contributions to getting that from bench into clinic. She’s got an incredible work ethic, attention to detail, and creative problem-solving that means she is constantly able to work magic to get things done on timelines with concrete and sometimes very creative solutions.

Then there’s Dave Tsao, our Chief Operating Officer. Sawsan and I worked with Dave during the Pfizer days, so it’s another 18-year-long industry relationship. His immense pharma background and steady hand have helped the organization grow smoothly and well. We had less than a week of operational downtime during our lab move a few years ago. Tsao made that possible.

Finally, there’s Nick Bayless, our Chief Technology Officer. I’ve known Nick since 2012, when we were completing our immunology PhDs at Stanford together. In the early days of the technology, he came out to teach our teams how to generate viruses in eggs for early testing. He’s been working on this with me since it was entirely conceptual.

It’s an excellent team that allows us to sort of “octopus out” and have each tentacle handle a different problem with expertise. And my job is to track between them.

Regarding processes, we hold regular meetings. It’s a strong culture of listening in because I think cross-training, having everyone pay active attention, and participating in problem-solving are really important. Then my job is to have people run things, and I come in, sometimes to support as a bad cop, or I ask if there are creative shortcuts that we should consider. And if it seems like we are stuck, I go and push. It’s my job to find a way to break reality.

That sometimes takes the form of leveraging my large network to put pressure on organizations to change their opinions and move things faster. Sometimes it takes charm, persuasion, pleading, whatever it takes. Sometimes it comes down to creating incentives. Sometimes it’s being an out-of-the-box Devil’s advocate (“why not run the first experiments in Guatemala?”).

It’s my job, when we are really stuck, to find a way through. But that’s everyone else’s job too.

NFX: What moments or milestones have stuck with you along your journey to the clinic?

There was a series of moments. The first one dates back to 2015 – there’s a Netflix documentary about the project’s early years. It was a couple of years after I developed the epitope focusing concept – an immune-focusing technology that could serve as the basis for a universal vaccine.

I grew up in Guatemala, so I have a relationship with the University of San Carlos, where I am an affiliate professor. And in the early days, we had built a small animal facility to run these vaccine studies in pigs with some academic colleagues in Guatemala. The idea was we would run the studies, isolate serum, RNA, B cells, and stuff down there, and ship them up to our laboratories, which, at the time, was the Distributed Bio laboratory (the last company I founded). There, we had sophisticated technology for characterizing immune responses.

All was going well, except around the time we were doing this, the international shipment rules changed – I think because of Ebola outbreaks happening in Africa. So suddenly, we couldn’t get them out of Guatemala. And those were the samples that would tell me whether I was wasting my time and my life on this project.

There were multiple months of delays, and finally, we resolved it. We got the samples up, and we derandomized the data. Someone in the lab took a picture of that moment. All at once, there was an overwhelmingly clear picture that it was working. That they were getting this universal response.

That was a moment when I was like, “Holy shit, this could be the most impactful thing I do in my whole life to contribute to the betterment of mankind.”

That same data was what I presented to Bill Gates in 2019, and we were awarded the Gates Foundation Grand Challenge: End the Pandemic Threat award. That supported additional studies in the United States using pigs and ferrets, and the data came out looking strong. These were challenge studies in which pigs and ferrets were exposed to viruses that had evolved years after the vaccine components.

And then another level-up happened after Jerry joined, and we decided we would run some optimizations. We had already had universality for years, but we wanted to increase the titers so we could outcompete the commercial vaccines even against the strains that they were designed for. We wanted to win everywhere.

We did a couple of things, and we significantly exceeded that goal. At that point, we’re ready to proceed with manufacturing.

I think those are the big steps. But it’s also constant. Even when we are applying for regulatory approval, we ran a study where we asked: “What about just the T cell focusing alone, without the antibodies? Is that enough?” Because we had a one-two punch going, of broad antibody focusing and broad T cell focusing, we ran some challenge studies to see how the T cells could protect even if the antibodies weren’t there. Those immediately demonstrated: both antibodies and T cells can provide broad protection independently. And we deliver both.

[Editor’s Note: A few terms to clear up. First, in this context, broad means protection against multiple versions of a virus, not just a single strain. Second, the team wanted to see if the multiple lines of the body’s defenses were providing broad protection. Antibodies act as the body’s first line of defense, blocking a virus from infecting cells in the first place. T cells step in when a virus slips through, finding and destroying infected cells. The team found that their intervention created broad protection in both lines of defense – the “one-two-punch” – Jake describes here.]

All three of those stand out as moments.

NFX: Interesting. Why does that “one-two-punch” stand out as significant?

So, Jerry likes to say that the immune system doesn’t fight these pathogens with one hand tied behind its back. And yet, historically, most vaccines have focused on antibody responses and not T cell responses. That’s because T cells are much more complicated.

Antibodies are these little Y-shaped proteins that float around in your blood and bind to the virus and block it. They’re very easy to test for. T cells, on the other hand, are complex. They’re making decisions about what they recognize and what they and the cells around them should do about it, sometimes directly attacking infected cells, sometimes secreting complicated signalling factors to rally and polarize the immune response. T cells are the “network-effects cell.” They’re the master architects of the immune response.

But they bind very delicately to an extremely complicated system called the Major Histocompatibility Complex, one of the most polymorphic parts of the genome, against tiny fragments of proteins which have been torn up for presentation. All of this unfortunately, makes them very difficult to analyze.

However, if you can figure it out, having both antibody and T cell immunity is a big deal. The power of having antibodies and T cells is that you have two different layers, like a belt and suspenders strategy of ensuring universal protection against flu infection – protecting you from getting infected in the first place. And then, if you do get infected, keep it mild.

And so our goal is to transform the relationship the public currently has toward flu vaccines. Where people say, “Oh, I took a flu shot, but I still got sick.”

That’s confusing to the population, and it’s a losing battle for epidemiologists to try to explain it to them. They’re used to experiencing vaccines like the tetanus vaccine, for example. If you take it, you don’t get tetanus. I don’t get sick, that’s the deal I signed up for. That’s what people want.

[Editor’s Note: This is one of the reasons we love Centivax. They’re actually increasing the size of the $7B vaccine market by creating products that live up to consumer expectations.]

So having a universal vaccine that gets us back into that 85-95% efficacy echelon against infection, plus the T cells on top of that layer…that’s a very complete form of protection, pending the results of our trials.

NFX: It seems like you set an unusually high bar from the start. Vaccines are given to healthy people, so expectations are already high, and on top of that, you were investigating both antibody and T cell responses. During the early COVID-19 vaccine work, most people focused on tracking antibodies. Here, it feels like you really tried to answer as many questions as possible before testing in humans.

Yeah, I think a lot of biotech investment can create these perverse incentives for people to really half-ass new tech. To spend as little time and money as possible on building a prototype, to spin it as just new enough that it can get sold at Phase I after some safety data, but it hasn’t really been tested whether it works or not. That’s never been our intention.

We spent 13 years building this technology because we believe that universal vaccines can be a historical passing of the torch moment from the work that Edward Jenner began 230 years ago. It could transform the human condition for centuries. Vaccines have been the greatest medical advance since sanitation and fire. And yet we still struggle with these rapidly mutating viruses.

That’s where our technology platform comes in. There are a lot of disease areas we could apply it to and have a huge impact on global lifespan and healthspan. So we built it for the long game. We have four follow-on programs we are already working on. With each platform, we reinforce and advance our core platform technologies as we learn things. The goal is to get stronger with each iteration. We want to build it right.

In terms of testing, the flu testing systems are a huge convenience. That’s one of the many reasons we chose flu first. Because they have to make a new flu shot every year in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, they created this accelerated approval process where you can take someone’s blood after they get a vaccine, test it to see how much it reacts to a virus, and that tells you if the person would be protected or not.

So we used that system. However, instead of doing the normal thing and testing only against the guidance strains, which consist of three outdated virus strains the commercial vaccines are based upon during annual updates, we are testing against a panel of 24 viruses, including the current 2025/2026 circulating strains, old pandemics, potential pandemic strains like H5N1, the guidance strains, and other viruses. We have a massive panel for establishing universality, and we get that out of Phase 1a and Phase 1b.

The T cell stuff we’ll monitor for, and anticipate that it could give rise to a significant advantage of avoiding hospitalization and death, which is the main reason that the elderly are vaccinated, as well as providing effective immunity even to those that are immunocompromised and might not otherwise benefit much from a flu vaccine. But those effects mostly become statistically evident during post-market studies, and thus we’re not dependent on it for our clinical studies.

The goal is an epoch-defining product to replace the current flu vaccines.

NFX: So, there is a quick pathway you can utilize with meaningful data, but you also have this secondary aspect that tackles the longer-term issue here…is that right?

Yeah. We wanted to get out into the market and become a disruptive replacement product. So that’s the layering that we created.

NFX: Okay, let’s switch gears to the present moment. You’re currently running your Phase 1a in Australia, right?

Phase 1a is in Australia. When you’re running Phase I studies, you don’t want to do it where there is currently the flu. It’ll confuse your statistics, and it poses an ethical issue if you have some folks, particularly elderly folks, in a blinded study who receive a placebo. We are in Australia now because it’s flu season in the Northern Hemisphere and not the Southern Hemisphere.

Then, for Phase 1b, it’s the opposite. We’ll switch to the Northern Hemisphere. So we are planning to do US and UK sites and maybe a Dutch site as well.

NFX: So, how do you get the groundwork laid to run all those trials?

Jerry, our chief medical officer, led that process. The way you do it is you engage these collections of contract research organizations (CROs) that manage clinical studies, and they have networks of clinical sites and PIs. They’re familiar with the regional regulatory process, and so you coordinate with them. We’ve been talking to them for over a year, for both studies.

We interviewed, did a bidding process, and ultimately picked one final group. Then you get very close to these people. They become part of your team. You run frequent meetings to review plans and coordinate. It’s all in the minutiae. Like, how long do they keep vials in the fridge, versus the syringe? You have to have all these conversations.

The CROs have really blossomed in the last couple of decades. Before, all this stuff lived in the big pharmas. Now, small biotechs can run GMP and clinical studies by connecting with these CROs and their networks. So you don’t need to build these capabilities as a prerequisite for going through human trials.

That’s empowering to the entire biotech ecosystem and to the public who will end up with many more medicines.

NFX: That change seems like it opened a lot of avenues for you guys.

It’s been empowering. I’ve been on both sides of that revolution: the last company I founded was a CRO. We did antibody discovery and optimization, as well as CAR T and a lot of other formats. Eight of the top 10 pharma companies were my clients, but we also worked with over 50 smaller biotechs that could advance on a target without building internal discovery expertise by working with us.

Now on the other side, it’s great that Centivax doesn’t have to be a big pharma to run GMP manufacturing. We don’t need to own and build the manufacturing sites where there are scientists in spacesuits building our vaccine. Those facilities exist at CROs now, and biotechs can tap into them.

Once manufacturing is done, we also don’t need a massive clinical network and a team of hundreds tracking everything in order to run clinical trials; CROs can do that for us as well.

The only part that hasn’t been fully wrested from big pharma’s hands is distribution. The big pharmas have a global distribution network and branding relationships with doctors worldwide. I think that social media and smart advertising could disrupt that space as well eventually: we see some of that already, but the revolution hasn’t fully happened yet.

Thus, these CROs mean that a company our size could complete a Phase III trial and obtain approval, but we would still need a pharma partner for global distribution. At some point it could change, but right now it would be irrational for us to attempt to do that ourselves.

So we aim to go all the way to approval and then see which of the vaccine pharmas is interested in partnering on taking over the $7B flu market and beyond.

NFX: So, you’ve mentioned all these things that companies no longer need, which seems great for startups. But what are the things you absolutely do need? What was essential to you?

You need to be able to build anything that’s not commoditized. You need to own those unique processes. So in our case, our platforms rely on advanced computational and bioengineering capabilities. The CROs can do established things that have already been done, but they’re not the people to develop a totally new and custom process for you. You want to own that.

You also just need the best people. You don’t need a lot of people, but you need the ones you have to be exceptional.

Finally, if you need to iterate rapidly, you often want to control the steps in that iteration cycle. So, initially, when we were exploring our vaccine, we outsourced it to test it for the first few times. But once I was like, “Okay, this is looking good, we need to optimize,” then we established each of those technology capabilities in-house.

That made it much cheaper and faster for us to run the iteration cycles that allowed us to optimize the final lead candidate. If you are depending on outsourcing for that, it will be slower and more expensive, and you will likely end up with a less polished final product. The cost of GMP and clinical is so massive, and the cost of engineering and optimization is such a relative rounding error, that I have always thought it was penny-wise and pound-foolish not to optimize the medicines.

So, systems you need to iterate on rapidly, innovations that are not already established methods, and a small army of geniuses advance the mission.

Those are the areas you want to control inside your organization.

NFX: What would you say are the highest leverage decisions you made as a founder during this journey?

The earliest decision that ended up having by far the biggest long-term impact was when I decided to conduct the initial 2015 testing of the epitope focusing platform in Guatemala.

The technology was theoretical at the time, and extremely different from the universal vaccine concepts that were being tested by others. I didn’t have my immunology PhD yet, let alone a lab, so there were none of the typical credibility-surrogate tools that venture or grant bodies could use to judge the concept, other than the mathematics. That made it nearly impossible to fund-raise or get grants for. But I was also obsessed: the mathematics were too beautiful to not test it.

I had founded Distributed Bio a few years earlier and it had become modestly profitable, so I stubbornly concocted a plan to build a small animal facility and tiny veterinary blood sample processing lab in Guatemala and test the universal flu vaccines on pigs.

I became an affiliate professor of the University of San Carlos and collaborated with my long-time colleague Dr. Erwin Calgua. It involved a lot of travel, large animals (pigs), having to get extremely creative about cold storage, transportation, and all manner of complex logistics – the opposite of the typical approach of academics going to test some mice down the hall. But the pigs were a much better model, and I was able to iterate rapidly.

We ran 5 rapid-iteration pig studies, and the early data, which were stunningly positive, demonstrated the technology’s feasibility. When I presented it to Bill Gates and several colleagues at the Foundation, we were awarded a “Grand Challenge: End the Pandemic Threat” grant, which accelerated the project with resources for follow-on studies. I owe a lot to those pigs and the early team who were willing to walk with me through that wild period of my life to demonstrate the early principles of the technology platform.

Another high-leverage decision was actually really hard and really inconvenient. But I stuck to my guns to really fight hard to keep hunting until I could pick a great group of grant supporters and investors. That was a bouncy ride. But we emerged on the other side of it stronger. Now we have a phenomenal board, smart money, and a united mission. Our board is highly effective, and our investors work with us to increase the asset’s shared value.

When you’re in the middle of the moment, you ask yourself: “This is exhausting, am I being too stubborn?” People around you advise you to take whatever money you can. But I didn’t do that. I pushed for what I thought was the right group of people. I understand that some companies might feel differently if this were a different project that was going to be flipped at Phase I. But this was a technology that could echo through the long arc of history and change the future.

My view was, “This has all the right elements to be tectonic – let’s build upwards only with slabs of granite.”

We wanted people who would lift us up and network us, and we saw the vision of how this could be huge, too. What we ended up with was an incredible group of investors and a powerful board. Steve Jurvetson at Future Ventures, GHIC, BOLD Capital, Kendell Capital Partners, Amplify Bio, and more. Emilio Emini and Pam Garzone on our board.

And of course, from the beginning, we got to work with NFX. I cannot say enough good things about how amazing Omri, Anastasia, and the entire NFX team have been as partners through this whole process, being there for us to problem solve during the tough days, a thought-partner always, and enabling the successes that we have so far achieved. That’s who you want in your corner.

So actually, that wasn’t a decision in a moment. It was a consistent philosophy.

The other was, again, not a moment but an idea that permeates the organization. I founded and ran a company before this, and while in high school, I managed my parents’ hotel and restaurant during my father’s illness. Even as a child, my father would often share his thoughts and strategies on how to organize teams in the quiet moments while we ate between busy times in the family restaurant.

I’ve watched over organizations and asked myself: what are the properties that make an organization excel?

The first part of it is, of course, the right people. I’ve always worked hard to handpick the best people, especially early in the life of an organization. I focus on bringing in people who are so good they’re scary. Slabs of granite.

There have been times where people have said, “Come on, Jake, let’s just get butts in seats.” And I’m like, “No. I think we want a luminary for this.” We want the best people possible, and I think it’s because in a small organization, there’s a huge effect of the individual. If you have a company that’s 10, 20, or 30 people, a single person can make all the difference.

So I’ve pushed really hard to get people who are so good they’re scary. I’ve made a point of being multidisciplinary so that I can effectively navigate strategy across the organization. The people I have brought on are better than me at the things they do by so much that I could never catch up.

The next key part is the culture. You can’t just toss an army of geniuses into a pot and hope for the best. To froth the army to victory, you have to work hard to create an environment where it’s the ideas we battle over, not the egos.

That is how you can harness the best energies out of those people and direct them towards changing the future. And that’s not an easy thing to do in science, where so much of what we do is in our ideas, and our ideas are often so closely tethered to our sense of self.

You have to figure out how to balance that and go: “Can I find a group of people that are exceptional? Can they work together? And can I create a culture where we can debate, and the debate is about collective problem solving as a team, where the idea is not something tethered within a single person, but rather something pulled out of us and shared by all of us, that we are all gathering around chipping at from all sides?”

The answer is yes, and the secret to success that has worked for me is that the culture needs to flow from me as the example. I make a point of publicly recognizing and valuing when someone on the team points out an error in one of my strategies or presents something better. “Yeah, that’s much nicer, let’s do that instead. Nice work.”

The message is clear: here in Centivax, bringing something better than another idea, anywhere on the orgchart, is valued and rewarded, because we all win if we go to war with the best plan. I can’t take credit for the entirety of our culture: we just have a great group of people. But I think actions like this from leadership can create a template for others and nudge the culture in the right direction.

However we achieved it, I feel like we’ve managed to succeed. That has had a huge impact on the momentum of the organization.

If you can make that happen, the magic happens.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.