From 2000-2006 I ran the world’s largest psychological testing website — Tickle.com. We had 5 psychology and statistics PhDs on staff at the company, and our goal was to develop a system for understanding human motivations in order to get products to go viral.

The project was essentially a success. Over years of studying psychological research and running experiments, we mapped 27 human motivation clusters, many of which help when trying to get people to share your product.

Putting these learnings into practice, we were able to virally grow our user base to more than 150 million people when there were only about 1B people on the Internet. It was one of the big social media viral success stories.

Since then, we’ve continued to apply what we learned to help startups grow. We’ve now helped 12 companies get to at least 10 million users each, including companies like Poshmark and Goodreads.

What I’ve learned is that the foundation of viral growth is rooted in motivational psychology and language.

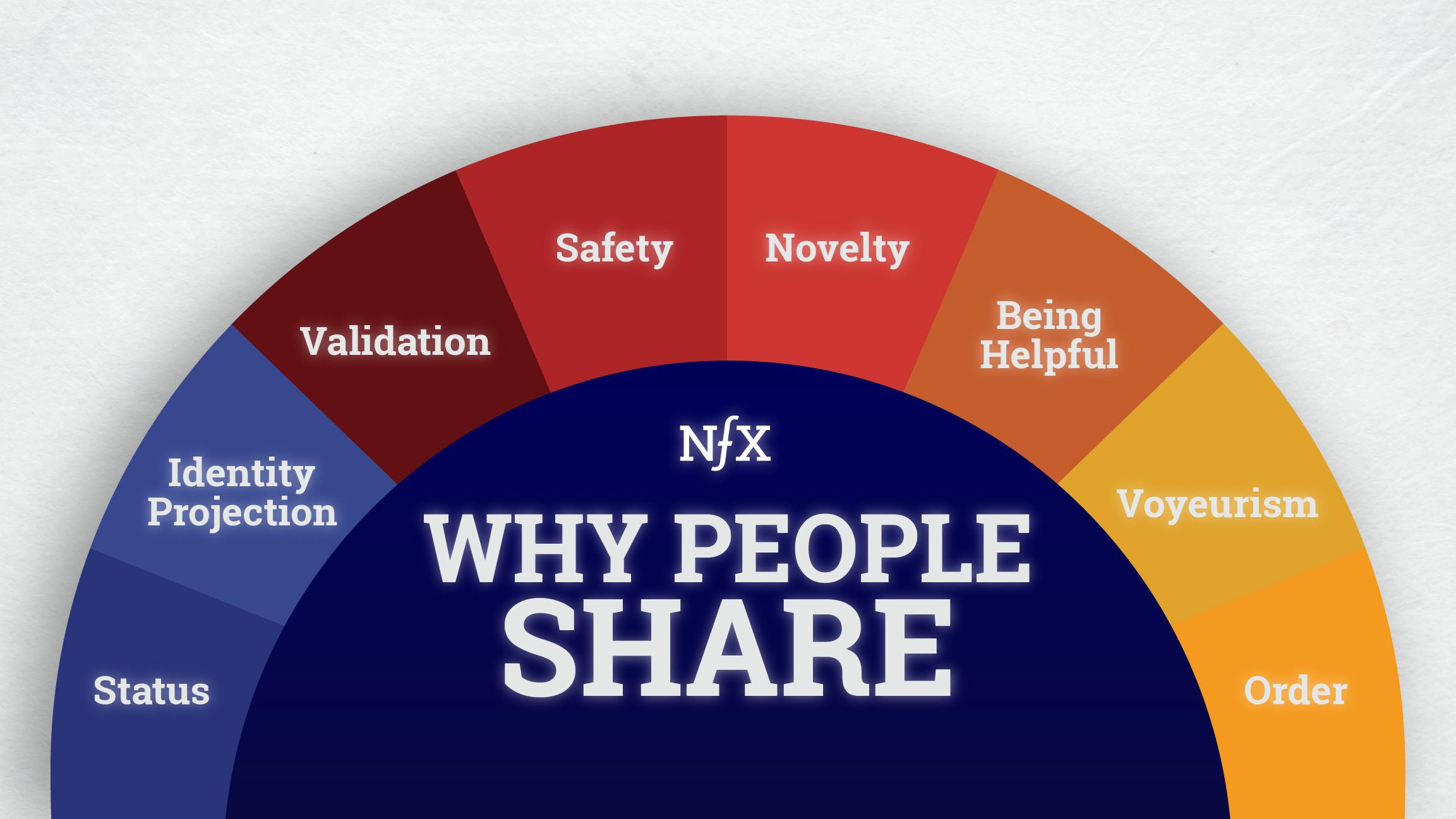

Today we want to share 8 of the motivation clusters that we found to cause people to share so that you can use them to engineer your product to make it more shareable and more viral.

Although virality and network effects are two different things, developing features and motivations that make your product a multiplayer game can lead to network effects. Thus, thinking through how to make your product viral often helps you plan to give it network effects of various kinds.

One of our goals at NFX is to encourage more founders to build network effects businesses. We hope helping you think through why people share will guide you down this path.

Baseline Viral Thinking

Each of the motivations we discuss below may or may not apply to your product. But there are several things that always apply.

First, is our pack animal psychology. As a pack animal, we’re constantly thinking about our status, how we’re perceived, where we fit in, etc. Those constant mental loops serve as the foundation of our motivations to share. We all worry about how sharing will make us look.

Second, reduce the friction to sharing. Design your product so that it minimizes the effort and thinking required to share.

Third, think about how to make your product broken unless people share. If they can’t get the utility that they want, they will look for ways to share.

Fourth, make your language about the user, not about you. This is very challenging for most product people, who are proud of what they have built and want to be recognized by users for their accomplishments. But this is juvenile. As product people and marketers, you have to transcend your own self-interest in favor of your users’ own self-interest. It’s more generous and more effective.

In short, when any of us consider sharing something online or offline, we unconsciously make a trade-off between benefit and costs:

- How might sharing this benefit me (the sharer) or you (the audience/recipient) either via utility or via status/reputation?

- How much time and effort (friction) will I have to spend to share this?

The differential between 1 and 2 will give you higher conversion to sharing, and A/B testing can help you with that differential. Growth tactics often focus on this.

Understanding psychological motivations expands your toolkit to maximize the differential and really speak to your users.

8 Clusters of Motivation That Trigger Sharing

Here are 8 motivations that trigger sharing. There are more, but these give you a good starting point. If you want to do more research, track down writings on the subject by Freud, Maslow, McClelland, Murray, Costa & McCrae, and Erhard.

With each cluster, we’ve chosen a word that we think best represents a cluster of words that speak to this core motivation. In each case, we list the other terms we’ve found similar. We include them all because each word could trigger a different idea in your mind as you think about how it could apply to your product.

1. Status

This is the big one. It can also be termed “belonging,” “prestige,” “respect,” “scarcity” or “in-the-know.” People often try to show this by associating themselves with other high-status people or central nodes in the network. Most of us intuitively understand that high-status nodes in a network tend to mostly associate with other high-status nodes.

They also try to show this by joining products that are exclusive, like Facebook was at the beginning when they were just in colleges, or like Superhuman or Clubhouse have been recently.

People also try to show their status within products. On social media, people share the accomplishments of their friends, for instance, congrats for making 30 under 30, raising a $X million VC round, getting a new job. They are happy for their friends, but the reason to do this publicly is also because of how it makes them look by association. The same thing is true in a CRM where you put in the data that makes you high status among the sales team.

Status is by nature scarce because it indicates the hierarchy of us in the pack. There is only one top position, one 2nd position, etc. Access to something scarce or exclusive motivates people to share because they can get high status from the people they share it with. Note that despite the high profile cases where this has worked, very few products can achieve high enough status at launch so that scarcity tactics work for sign up. Scarcity typically works more easily for things like discounts or tickets that are limited in number or time.

2. Identity Projection

Other words in this cluster include: “tribalism,” “vindication,” and “confirmation bias.” We want to be able to show who we are and be vindicated in our identity.

This motivation is especially visible with outrage-sharing on social media. When we express outrage around something, we’re drawing a clear line around what we aren’t. This is the reason why so much of what people share online is in the camp of “I told you so” or “this vindicates my perspective.” “I’m right.” “My team is winning, so I’m worthy.”

Sharing an outraged Yelp review or political Facebook post helps us define what we stand against, and by implication what we stand for.

It gives us an opportunity to have a point of view — a statement that people can agree with or disagree with. We mostly seek validation in that point of view. Sometimes, however, interestingly enough, we share to help us explore our own identities, or to explore the identities of others. To see who has a like-mind. Examples of this are things like Roblox or having multiple accounts on Instagram.

“Tribalism” is a powerful human motivation baked deep in our psychology that says we are right and they are wrong. We will be successful and they will not be successful. We want to be part of the pack, and when we share, it is sometimes to either A) signal that we belong or B) help us find our tribe.

Community-driven sharing that signal belonging is evident in online communities like the WallStreetBets, where using a common lingo (“Diamond Hands”, “To The Moon”, “Hold The Line”) signals belonging and helps grow the tribe by increasing awareness of it.

It’s not just online communities that are shared out of the motivation to belong. Many types of products can build tribal network effects. Such products will draw on the underlying psychology that motivates people to share, either to recruit new people into their tribe, to signal their membership in it, or defend their tribe — and thus themselves — from others.

3. Being Helpful

“Utility.” “Better.” “Cheaper.” We are compelled to share things that we find useful because we want to be perceived as helpful and nurturing to our tribes. It feels good to be looked at as someone who is competent and knows what you’re doing.

Whether that be a new product that we feel really improves our lives by producing a lot of value or something that produces that value at a lower price.

For instance, in the early days of Airbnb, people were motivated to share the product because it produced so much cheap value for them as users, and they wanted to share that utility with their friends. The same thing was true of Salesforce in the early days, $50/month for a CRM in SaaS form.

Note that language is important here, especially if your product provides some new or unprecedented utility. If you can give your users the language to express the utility of your product in a clear, pithy, and compelling way, it will 10x the word of mouth. It’s the difference between saying “access an online rideshare marketplace” and “get a ride in 3 minutes.”

4. Safety

“Fear.” “Compliance.” “Prevent harm.” “Security.” Fear is embedded in the most primal part of our psychology. If we sense danger, our brain has evolved to pay attention.

Any perceived threat to safety — whether physical, financial, or emotion — can be a powerful reason why people share. News media have long understood this. As they say in the biz, “If it bleeds, it leads.” And it’s why the cliche way for the 6 pm TV news to get you to watch their 11 o’clock news is “Are your children safe? News at 11.”

Products that offer safety or security are shared because of the same emotions. For example, Nextdoor’s early growth came from people wanting to know what was going on in their neighborhood and what kind of threats to their safety they might face. The app Citizen grew for a similar reason, and it was also why Trulia’s crime map helped them grow.

The same applies to digital safety products like Norton Antivirus or password protectors like 1Password. Users share with their friends and family to help protect them from danger.

Related to safety is compliance — people are highly motivated to prevent harm and maintain stability. Customers of compliance SaaS software, for example, will be motivated to share with others in their company so that they can be perceived as wanting to prevent harm and being a protective, stabilizing force.

5. Order

“Organize.” “Collect.” One of the Big Five personality traits is conscientiousness — people fall on a spectrum between personality types that like to be highly organized and efficient and those who are naturally messier.

People who are trying to organize their world because of their personality are highly motivated to share tools that help them to optimize and organize.

This is one of the big drivers between the rapid growth of a cult-like following behind note-taking apps like Roam Research and Notion, which have been virally growing for the past few years. It is the same thing that drove the growth in the early days of productivity software like Asana and Airtable.

People share them not only because it makes others perceive them as more organized and efficient, but also because it helps them bring other people into the same protocol of organization— whether it be co-workers or friends and acquaintances.

6. Novelty

“Entertainment.” “The new.” Another aspect of personality identified as part of the Big Five is openness to experience — where we fall on a spectrum of being driven by seeking novelty and curiosity to being cautious and preferring familiarity.

The attraction of novelty was identified early on by Wilhelm Wundt, one of the founders of modern psychology who came up with the Wundt curve — a bell-curve distribution between novelty at one end and familiarity at the other.

The sweet spot is in the middle — we are attracted by things that are new enough to not be stale, but not too new to be strange.

This novelty sweet spot can be seen in internet memes, where people share remixes of the same formulas which contain elements that are both familiar and new. Formulas from 2020 like “how it started… How it’s going.” “Nobody:… “Absolutely nobody.”

At some arbitrary point, the meme moves past the sweet spot and becomes stale, after which people stop sharing it because they’ll be mocked for being behind the curve.

At the same time, we are always looking for the next new thing. We are motivated to share new products and new information because it makes us look like we’re ahead of the (Wundt) curve.

People share things that are entertaining because the risks are low and it allows people to interact in bond in ways that feel safe and warm.

My threshold to send something to you drops if I know it’s going to be entertaining or fun. The perceived risk of sharing something entertaining is always low, while there’s a clear benefit of being perceived as having good taste for entertainment.

Competition makes entertainment virality a difficult motivation to capture. Worst of all, it’s very hit or miss and then fleeting even when you do hit. You often need to create 50 pieces of novel, entertaining content before one “hits” and then it typically lasts for a few days or weeks before it gets forgotten in the market under a torrent of new novel pieces.

7. Validation

“Positive.” “Happy.” “Smart.” A lot of what we share online has to do with the fact that we want to get a boost, believe we are good, believe we’re smart, or believe we’re worthy. We want to feel positive about ourselves and our place in the world.

At Tickle, we noticed this a lot with personality tests. People shared their results because they wanted to be validated and boost their self-esteem. Even today, people are often eager to share the results of their Myers-Briggs or Big Five personality tests with their friends because they seek that validation.

You want to know what people think of you, and you will share products that help you do that. You also want to feel positive and uplifted. Upworthy, for example, went viral because it helped people feel good about who they were and validated their positive views of themselves and the world.

8. Voyeurism

“Window.” “Schadenfreude.” “Access.” There are two related motivations that cause people to share out of voyeurism.

On the one hand, you have vicarious enjoyment. People share things that allow others to vicariously live through them, whether it’s instagramming their food and vacations or sharing a product unboxing on YouTube.

On the other hand, there’s schadenfreude. People are highly motivated to share things like celebrity scandals, gossip about high-profile people or people they don’t like because it helps unit them with others in common judgment/disdain.

Although this isn’t pretty, it’s two sides of the same coin. Voyeurism is a powerful motivation in why people share.

Always Return to the Psychology

As a Founder, understanding the psychology of why people share is one of the keys to unlocking growth. Experimenting with language to connect with these motivations is the work to be done.

Too often, we miss the forest for the trees — we focus overly on A/B testing, optimizing conversion funnels and landing pages and app designs, while not focusing enough on the psychological and language fundamentals that motivate our users to share our product (or not).

Understanding and applying the psychology of why people share is the Pareto Principle of marketing — it’s the 20% of what you do marketing and product design that will ultimately lead to 80% of the growth.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.