If you’re a Founder looking to fundraise venture capital, the first thing you need to understand about the process is that it’s far more complex than it appears.

Fundraising is one of the most challenging parts of being a Founder because it most often works opposite your instincts. It is just as much about what not to do as it is about what to do. Instead of relying on traditional best practices, it’s the non-obvious insights that will bring you the most learning, leverage, and ultimately, the best Founder-Investor partnership (and success) over time.

Why is fundraising so challenging? Because it’s supposed to be hard. It’s a filter for groundbreaking ideas and top Founders from all around the world. When you look at the numbers, it’s clear how hard it actually is. For any given meeting with a VC, the chance it will result in funding is between 1% and 10%. Less than 50% of companies ever raise their second round, and at every subsequent round, almost 50% of companies fail to raise. If it were easy, everyone would do it.

Like much else, fundraising is not an instant and innate talent. To succeed you’ll have to train your fundraising skill like a muscle with practice and time. The fundraising process will cost a lot of your time, energy, and attention. You will make mistakes along the way. But it’s a strategic competency that as a startup Founder you must master — or you may not be able to build a winning company. Mastery will come from learning at great speed and seeing what others do not, which is why we wrote this guide.

Over the years, my partners James Currier, Pete Flint, Morgan Beller & I have given a number of private talks to the NFX Guild about fundraising. Those talks draw from our own experience as Founders who have collectively built 10 companies worth 10+ Billion dollars — and from our experience as VCs who currently work with world-class entrepreneurs every single day. We’ve done and seen a lot of fundraising; the companies we built and funded raised billions of dollars, and in this guide, we share what made this possible.

With this guide, we are making public some of our playbooks for your direct benefit as you kick off your fundraising journey.

As above, fundraising is a complex topic; this is a living document that we will be updating and expanding on over time.

5 Mental Models Of Top Founders In Fundraising

Before we get into the actual playbooks, there are a few foundational mental models that we’ve observed in top-performing Founders. These will help you set your own expectations, be an exceptional communicator, and increase your chances of fundraising successfully.

1. Know What You’re Likely To Get Wrong

Fundraising is not a natural talent for most, and it’s easy to make mistakes in judgment along the way. Here is a list of the most common mistakes we see Founders make time and again in their understanding of fundraising:

- Misjudging the level of a prospective investor’s interest.

- Underestimating how long the fundraising process will actually take.

- Not understanding or accurately predicting the terms that you’ll be offered.

- Hearing a “yes” when the investor actually said “maybe.”

- In general, misperceiving what the investor really thinks of you.

Chances are, one or all of these things will happen. Why? Because investors play this game all day, and you only do it occasionally.

So don’t trust your instincts too much. The more awareness you have about the limitations of your startup fundraising experience compared to those of VCs, the more empowered you will be throughout the fundraising process and beyond.

We recommend that at the end of every fundraising week, stop and reflect: What have I learned this week? What could I be interpreting wrong? Am I really seeing things the way they are?

2. Divide & Conquer

Before starting out, it’s important to assign clear fundraising roles within the team.

Choose just one Founder to be in charge of fundraising. That person should be the CEO. This will feel uncomfortable to many Co-Founders because early-stage startup teams are often made up of people who wear many hats and collaborate as a habit. But fundraising is a time to divide and conquer.

It’s possible that in some teams, other Founders may be more suitable to do the fundraising work, but the reality is that investors expect the CEO to lead the charge. Delegating fundraising to another Founder is likely to raise many questions that will likely outweigh the potential benefit.

The CEO should decide whether you need other Founders or team members in initial fundraising meetings. This varies between teams and fields. However, in general, aim to reduce the fundraising workload of everyone other than the person leading the process. The rest of the team should focus on the actual business as much as possible — the progress of the business is going to be critical to your fundraising success. In most cases, the most balanced approach is to go CEO-only for the first meeting and include the full founding team for subsequent meetings.

Founders often complain that fundraising is a distraction from the day to day running of their company — but thinking of it as a distraction means you haven’t laser-focused on fundraising as your priority. As the CEO, understand and accept that fundraising isn’t a distraction — it is your biggest mission-critical task.

3. See Your Pitch As A Product Launch

Many Founders miss the fact that your company is itself a product, and for the customer (investor) to buy (invest in) it, you need to be as prepared as possible. As a Founder you wouldn’t go to market with a sloppy website or bad first-time user experience — why do that with fundraising?

To start, make sure you have the best fundraising material: including a polished and rehearsed pitch deck, one-pager, and a financial model. Even the wording of the emails you send should be tested and optimized. We’ll cover all of this more below.

Your actual product is also part of the funding materials. Clearly what you can present depends on what stage or field you are in, but investors will want to see your product skills one way or another. Having the product actually working to play with is a huge help; if the product is not ready, have great mockups, preferably interactive. Very very early stage founders might not have a product yet, but that shouldn’t stop you from getting creative about how you can showcase your product skills in a lightweight, high-leverage way. Make sure you have something that explains the flow of the product. Convincing investors your team has great product skills will go a long way.

Second, build a process. Just like you use a CRM system to track all your customer interactions, follow up properly, and personalize the interaction with any customer, you must do the same with potential investors. Do your research on investors, run a tight and up-to-date investors spreadsheet (or use a CRM tool), and make yourself reminders for when you need to interact with every investor. This is a very complex operation, and before the very first meeting is the time to create an organized system for it.

Third, do as many practice runs as you can and get feedback and comments, especially from peers who have gone through the fundraising process themselves. We would even recommend recording your rehearsal presentation on video. You only get one chance to get an investor’s attention and if you are not as prepared as you possibly could be, you are reducing your chances dramatically.

Your company is a product; your pitch and sales tools are how you sell it; and the investors are your customers. Work hard to be the best salesperson in this process!

4. Focus On Learning, Not Just On Money

Top-performing Founders know something that others do not: when you meet with VCs, don’t just fixate on getting their money — learn from them and from the process.

For any given meeting with a VC, the chance it will result in funding is between 1% and 10%. That means you have 90+% probability that you will not raise money from this specific person. So if that is your only goal for that meeting, you are wasting 90%+ of your meetings, plus your time, plus their time.

It’s better to view the meeting as an opportunity for you to build your company and improve your fundraising skills using the information you get from the VC, not just the money you might get. This will give you a higher return on your time and increase your chances of eventually fundraising.

Remember that investors see 1000s of companies and have invested in 10s or 100s (in rare cases) of them over their careers, which means they’ve likely seen different insights than you have. They see and hear things that you may not. This wealth of experience is sitting right in front of you. The way they evaluate your startup, the questions they ask, and their feedback on your pitch are a treasure trove of feedback that may help you win the next pitch. Learning as you fundraise is critical — whether or not you get good at fundraising depends on whether or not you learn.

Think about it like this: an average funding process may include something like 50 meetings. If you improve your chances by just 1.5% in each meeting by learning something new, you have double the chances of raising by the end of the process. You just need to learn what to ask and remember the most confident people are the curious ones who ask a lot of questions. If you can manage this, you will probably be surprised by how much helpful feedback investors are willing to provide when asked.

One small habit to ensure you learn after each meeting is to force yourself to change at least one thing in your pitch after every meeting. This can mean anything from adding a new appendix slide, to changing a number or a sentence in the deck, to deciding to cut or add something to what you say in the next meeting. By forcing yourself to change at least one thing, you’ll ensure that you take advantage of each learning opportunity and continually improve.

Top Founders embrace this growth mindset while fundraising. For example, here’s what Poshmark Founder & CEO Manish Chandra had to say on the subject of building one of the world’s most successful marketplace companies via the NFX Podcast episode “What It Takes to Build an Iconic Marketplace: The Poshmark Story”:

“What I find is that in general when people are giving you feedback it’s very hard to accept it in the moment, but there’s wisdom in it. Even in the worst critic, there is wisdom. When investors are criticizing you, if you can absorb it, there are ways to process and evolve. I believe if the leaders are not growing, then the business can’t grow.”

5. The Surprising Benefits Of Early Stage Chaos

It’s often said that success is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. In other words, 1% of success comes from the idea and 99% comes from execution. We disagree.

While this might be true at later stages, at the initial stage of a startup, the core idea makes a huge difference. Small changes in your initial idea or direction will make a big difference to where you end up.

It is also true that ideas that just don’t “sound right” will cause investors to pass on your company. Investors frequently say that in the early stages they care about the team more than the idea, but here’s a little secret: when the idea is bad (which is different from weird) it immediately reflects on the team in the mind of the investor.

A great idea is a multiplier for all your efforts down the line, compounding over time, and makes fundraising much easier at the early stages. A bad idea wastes your life’s energies and makes fundraising much tougher.

In fact, the biggest waste in our startup/VC ecosystem is great people working on mediocre ideas. Many of the “no” responses Founders get happen because the investors have seen the pattern of how similar ideas played out before and intuitively know it’s not going to work. Yes, they could invest in a great team with a not-great idea, but why not wait for the whole package?

So, especially at seed stages, VCs will often look at your early idea and want to tweak it. You don’t get brownie points for conviction or loyalty to an idea if it makes you blind to good feedback. Listen to the investor and be open to a little Chaos Theory, which says: “Small differences in initial state yield widely different outcomes.” Often by listening and tweaking your idea at the early stage you will improve your company — and your fundraising success rate.

Additional Resources:

- The Winning Psychology of Top Founders In Fundraising Meetings: 40+ Questions For A Winning Mindset

- The Hidden Patterns of Great Startup Ideas

Getting Into The VC’s State Of Mind

Like so many of the Founders we work with today, when we were running companies, we always felt a disconnect between the way we saw reality and the realities of VCs we met along the way. It sometimes felt as if we were not speaking the same language.

Looking back, it makes sense. We were deep in the trenches of the Founder ecosystem, didn’t really know the VC mindset, and didn’t always understand them. We weren’t speaking the same language. But, over the years, we learned the hard truth: for a startup, understanding VCs’ mindsets is often as important as understanding the mindsets of your customers. With no capital most Founders will not win, so you’d better learn the language.

As VCs, we now see the interaction from the other side as well, and it is clear that the disconnect is still around. To help bridge the gap, sharing a few psychological drivers that predictably dictate many VCs’ mindsets and decision-making processes. These are patterns we often failed to see back when we were building companies, and our hope is that Founders can learn them to master the skill of Founder/VC communications.

One of the biggest and most overlooked advantages you can have going into fundraising is the ability to understand the person you’ll be interacting with and who will ultimately become a collaborator in your business. Fundraising is not about closing the deal — it’s about choosing the right partners and convincing them to partner with you.

We’ve broken this section into two parts: “How VC Firms Work” and “How VCs Think” so you can understand the business math as well as their psychological drivers. If you are familiar with the structure of a VC you can skip the first section — but over the years we have often been surprised to learn how little Founders know about how VCs actually operate — and what an advantage it is for those who do.

1. How VC Firms Work

To understand how VCs work, first you need to understand the typical firm’s structure. Here are the highlights.

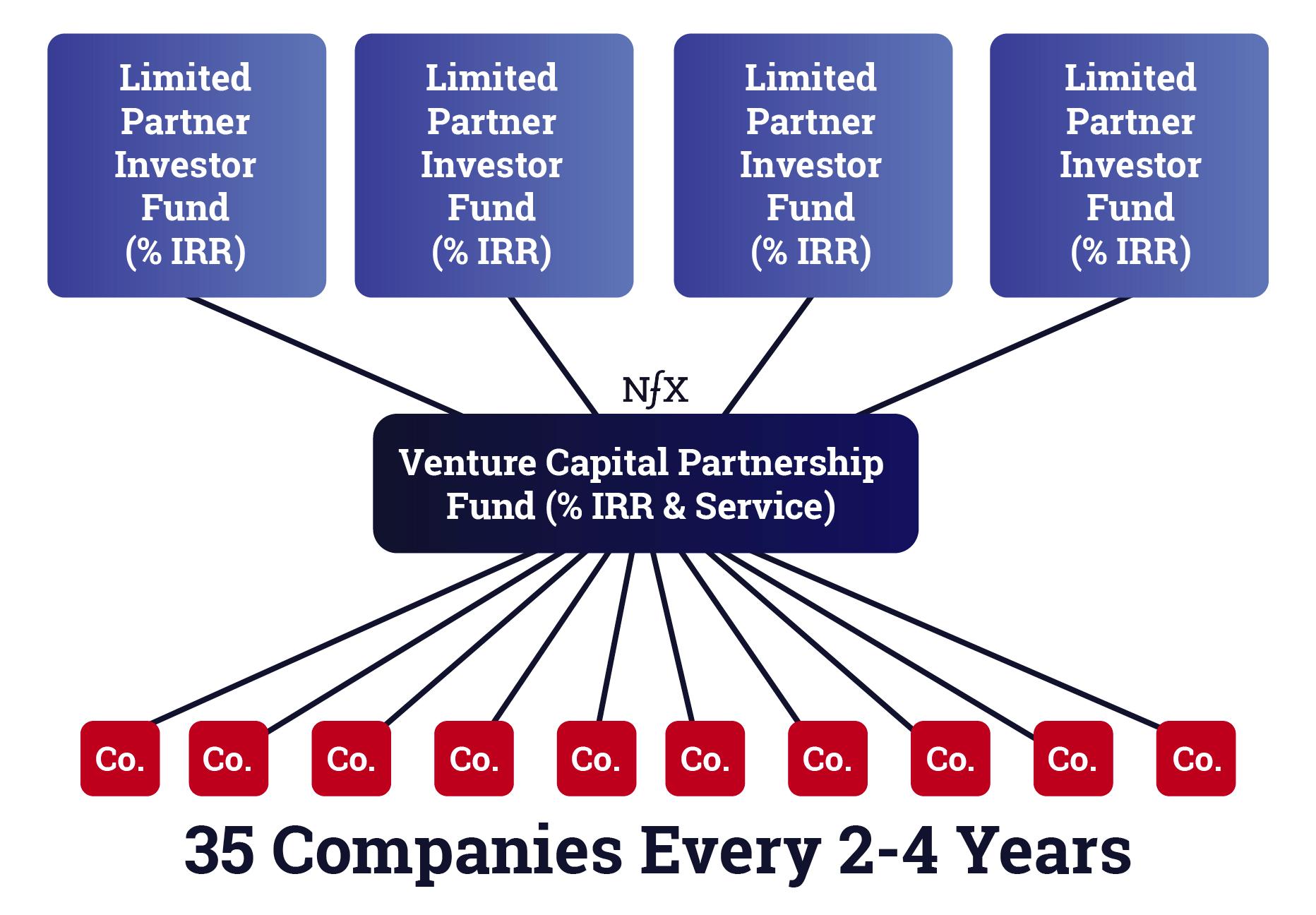

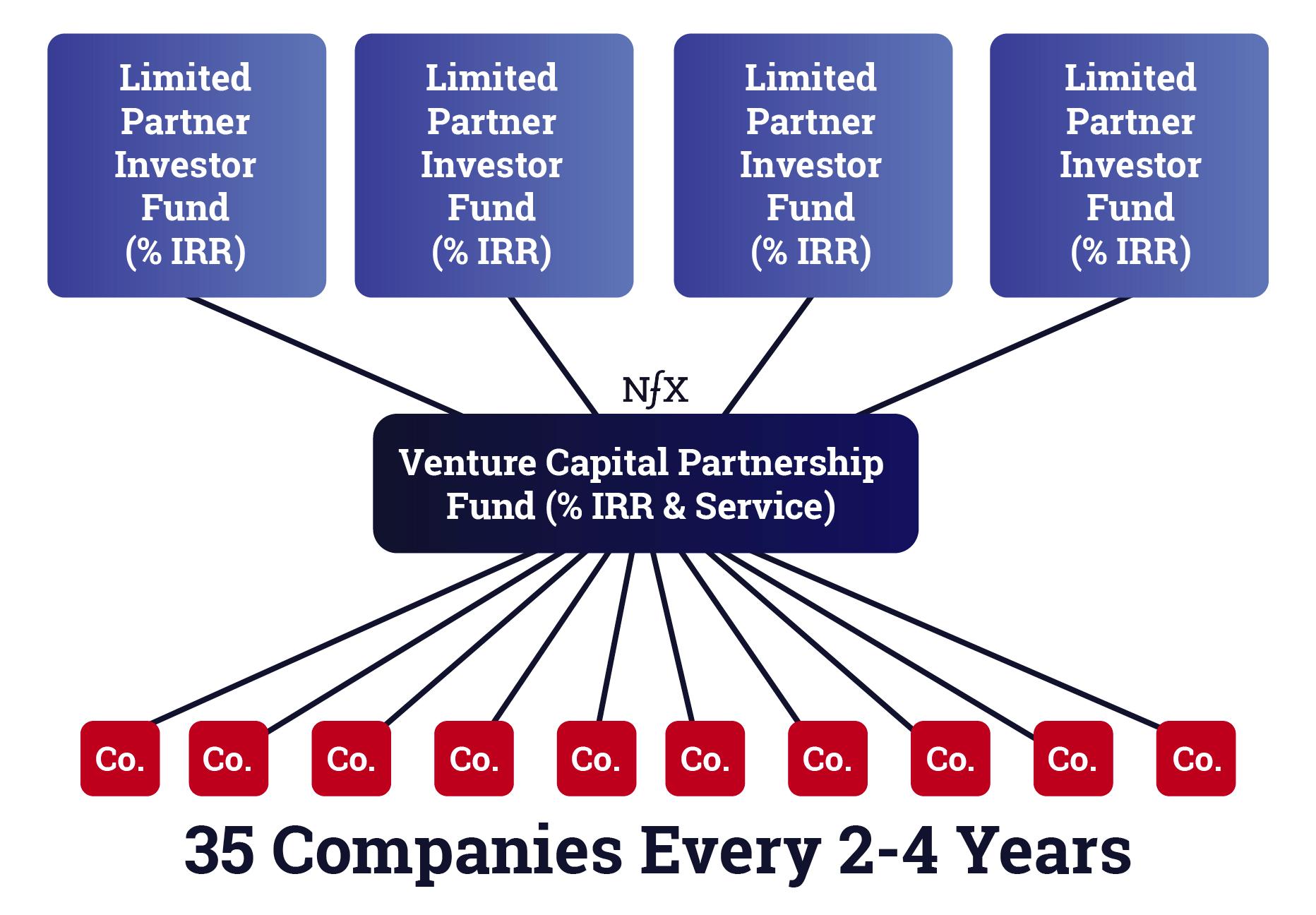

- VC firms are partnerships comprised of LPs and GPs.

- LPs (Limited Partners) are investors in the fund who provide the majority of the fund’s capital but don’t actively take part in investments.

- GPs (General Partners) are in charge of making investments for the whole fund. They usually contribute ~5% of the fund’s capital, so they also have skin in the game.

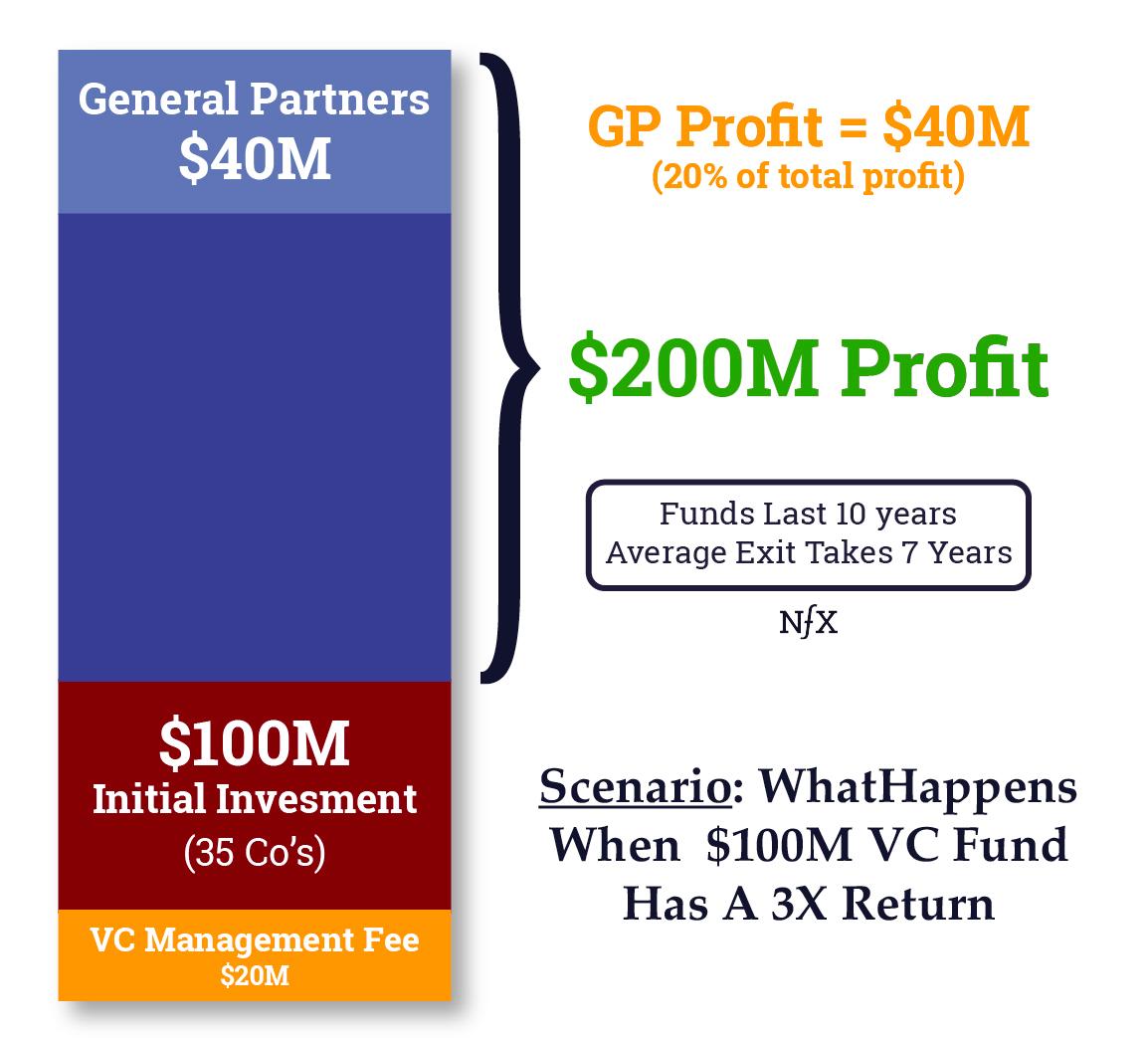

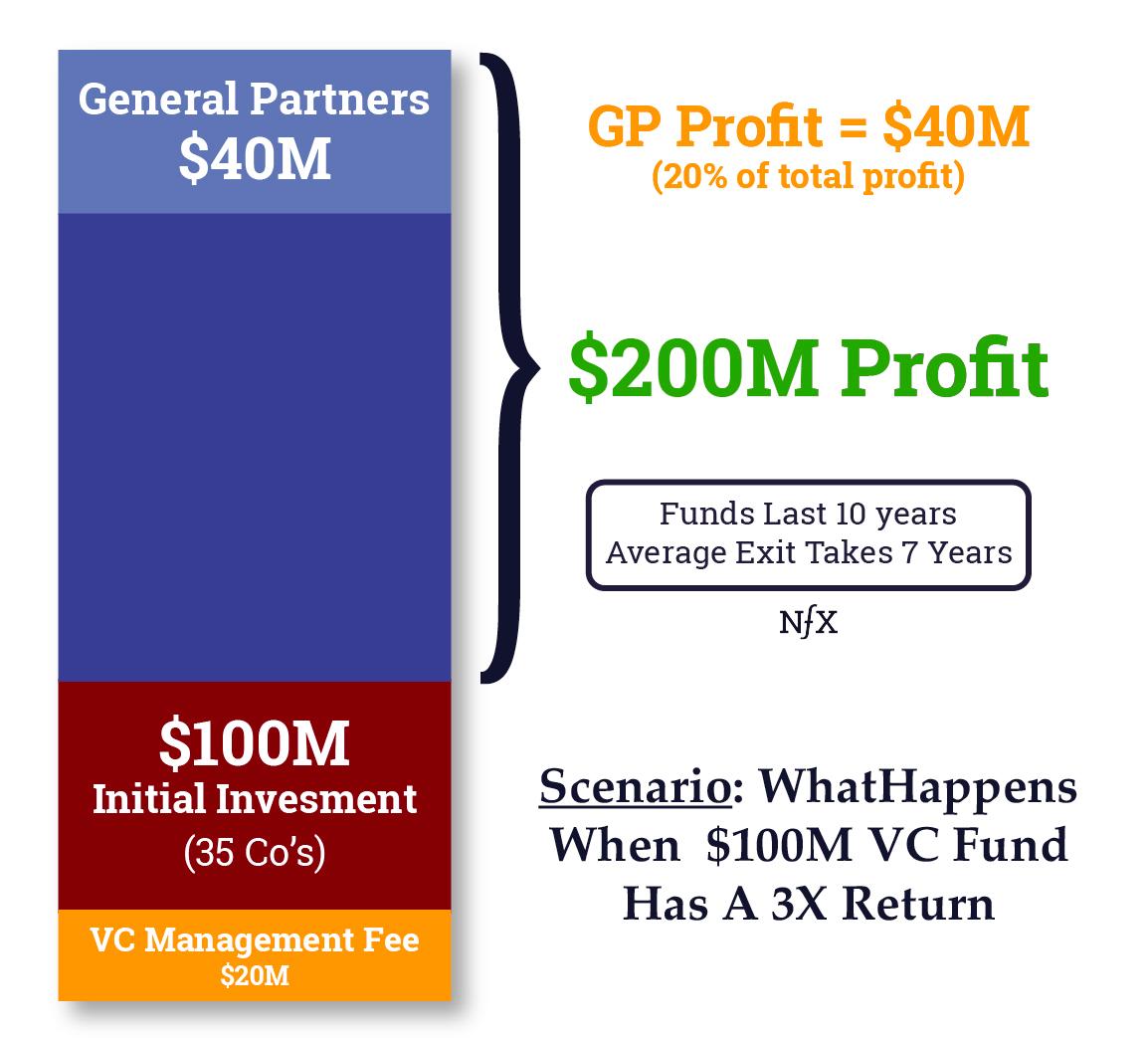

The diagram above shows the firm structure of a typical early-stage VC, with LPs contributing capital (top layer) to the fund managed by the GPs (middle layer) who deploy that capital to a portfolio of startups they invest in (bottom layer). The number of companies the fund will invest in depends on the fund’s size and the stage it invests in.

In addition to GPs and LPs, VCs typically have investment team members with other roles and titles. Some of the most common you’ll encounter are:

-

- Managing Partners – Higher up than GPs in some firms, but they still mostly act like a general partner and can make investments like general partners. Usually, these will be the more senior partners, but any GP can usually lead investments.

- Associates/Principals/VPs – Associates and Principals can be seen as a filter layer between you and the Partners, so having a direct partner intro is preferred. But if there’s no warm direct intro to partner, then Principals (in some funds) can be your champion and internal advocates if they believe in you.

- Analysts – They do the research but don’t have any decision-making power. However, that doesn’t mean they don’t have any influence, so be nice! The analysis they present can often impact the partners’ decisions.

Understanding VC Math

To negotiate with investors you have to understand their financial incentives.

VCs charge investors (LPs) 2 – 2.5% annually on invested capital, called a management fee. This is what’s used to pay the operating costs of the firm (salaries, office space, etc.).

Beyond this, they take 20% (and sometimes slightly higher when returns are high) of carried interest (profits) on exits from the portfolio calculated after a hurdle rate (which is the profit that goes first to the LPs), usually for the entire fund.

Here you can see what an outcome might look like for a VC whose fund returns 3x on a $100M fund. Out of the final fund value ($300M), there is $200M in total profit, 80% of which goes to the LPs. The remaining 20% in carried interest goes to the VCs, in addition to their annual 2% management fee which after 10 years would amount to about $20M.

To get to a good outcome like a 3x return on a $100M total fund, on average, out of every 10 deals, a VC expects 1-2 of them to be “home runs”, 3-4 to be positive but modest returns, and 4-5 deals with no return.

While good VC funds return 3X+ the invested capital (and top-tier ones can even achieve 10x), most VC funds don’t even return the original investment. Understanding what drives VC success is important for your fundraising success.

How VCs Make Money

To understand how VC firm structure, decision flow, and deal terms impact their point of view, let’s imagine a hypothetical scenario bringing together what we’ve learned.

In this scenario, say a VC invests $10M in your startup at a $30M pre-money valuation and $40M post-money valuation for 25% equity. In further rounds, the VC invests another $10M exercising its pro-rata rights to keep 25% equity in your company.

Consider two possible outcomes:

- Outcome A: After 3 years, the company exits for $80M. The VC gets 25% of the outcome – $20M which equals the VC investment of $20M. Outcome: there is no profit for the LPs and hence the VC Partners get $0 carried interest because there was no profit.

- Outcome B: After 3 years and some additional 20% dilution from subsequent rounds and ESOP, the company exits for $1bn. The VC now has only 20% so it gets $200M and the partners get 20% of the total return ($40M). This is a good outcome.

It is important to note though that VC partners get the carried interest (their share of profit) on the entirety of the fund, so if the rest of the fund was bad and the total return was below the hurdle rate (total fund investment amount + minimal profit for the LPs), the VCs still may ultimately get no carry from this deal. Only if the entirety of the fund will be profitable will the VC partners get the carried interest.

The difference between outcome A (a modestly successful startup) and outcome B (a successful startup) for the VC is therefore quite stark. This helps surface two critical things about a VCs point of view that every Founder should be aware of when fundraising:

-

- VCs really need large exits in order to A) clear their hurdle rate and B) make up for investments that don’t work out, which there will be a high number of since startups are inherently risky investments. That’s why you must convince potential investors that the outcome of your startup can be huge.

- VCs need a big stake (15%-25%), because it’s a hits-driven business and if you have low equity in a hit, you don’t get enough of a return. Seed funds will usually have a threshold of 10% ownership in any company they invest in and A funds will aim for 20%. That’s not because of simple greed for ownership; it’s their business model. Without meeting this minimum threshold of ownership, even the best company will not help return the fund and get the VC into the carried interest range. Imagine the FOMO pain resulting from the fund holding only 3% in the company that could have returned the entire fund. And at lower percentages of holdings, you need even higher overall exit value. Big stakes are critical for VCs.

A Look Inside The VC Decision Process

Usually, VC firms have a standard process for how they make investment decisions, although steps can vary across firms.

Understanding this process, and knowing exactly where you stand within it, is critical for you to be able to navigate it successfully. By understanding this roadmap, you can have a sense of how far your fundraising efforts have progressed with any individual VC you’re talking to.

Here’s what to expect going in when you start talking to a VC:

- The first meeting with the interested partner: this person is usually your champion in the firm, and if you aren’t able to pass muster with the first partner you meet with, you are unlikely to meet another partner.

- Second meeting with champion + 1-2 other partners and associates. The goal of this is usually for the initial partner to see if there are other positive opinions that concur.

- The VC performs diligence calls on your company. During this part of the process, analysts may ask you for data to run an analysis on, and the fund may consult with industry experts to get further opinions.

- If the leading partner decides this is an opportunity they want to pursue, they will invite you to a final partner meeting where all the partners hear your pitch and ask questions.

- After your pitch, the partners will deliberate amongst themselves and make a final investment decision. This will usually take place during their weekly Monday partners’ meeting. During this meeting, the partners will vote on the deal. If it’s a competitive deal — i.e. if other firms are interested — they may decide on the spot.

- If the deal is not competitive and there is no unanimous decision (as is often the case), the partner may continue diligence and bring the deal back for final approval.

Different funds have different required majorities to make an investment, but in most cases you need the partners to concur unanimously in order to receive an offer. At a minimum, then, a majority of partners must agree. The exception is small investments (amounts between $500K-$1M in large funds) where a single partner (or two partners in some cases) can sometimes decide on their own.

It is important to know where you stand in the fund’s process, and if you are not sure, it’s perfectly fair to ask the VC questions like “what’s the next step?’ or “if we proceed, do I need to meet the entire partnership?”

Not knowing where you stand in the process may lead to the wrong analysis of the situation and could lead you to take the wrong actions in your bigger fundraising journey.

It’s also important to understand that this is a very delicate decision-making process. VC decisions involve many variables and people who influence the decision, so any one investor’s decision about whether or not to give you money can seem capricious or whimsical. A single negative comment from someone ‘important’ can kill a deal, and this is sometimes beyond your control. The faster you move along the decision process – the fewer chances you give the process to derail, so make sure you keep the process going and move from one step to the next at the highest speed possible.

The Day-to-Day Life Of A VC

The last part before moving to the VC’s psychology is understanding the day-to-day life of a VC. Contrary to popular belief, it’s not all fun and games.

- VCs get 10s of pitches each day, which can become exhausting. It’s never clear where the next great company will come from, so there’s a high level of randomness in what they do. It’s much more random than many people think.

- Many companies that they meet with have ideas that seem uninspired and they see many poor presentations. This means they have to endure lots of useless meetings and have to say no all the time while staying nice. [Of course, this is good for you who are reading this guide, because it means you can stand out with your preparedness and strong ideas!]

- What’s more, their jobs are never done — they could always do another due diligence call or go to another lunch to find out about another company. There’s always more they could be doing. That feels both exciting and daunting at the same time.

- Last, there’s the politics with other partners. Since funds are a democracy, there are usually a lot of interpersonal dynamics at play and the baggage from past decisions and disagreements can affect the VC’s psychology and decision making.

By putting yourself in a VC’s shoes, you can see how many different factors are at play that might affect whether or not they say yes to your company — everything from interpersonal dynamics at the fund, to how tired they are that day from hearing pitches, to how risk-averse they are at that point.

2. How VCs Think

Beyond their incentives and constraints, the other thing you need to understand to successfully negotiate VCs is their personal inner psychology. Now that you understand the incentive model, you must learn the psychology this incentive model creates.

Certainly, the VC’s individual desire to solve certain big problems in the world — or a moral code driving them to do good at scale — will influence the companies they gravitate toward or not. But from a business perspective, let’s look at how the financial model causes them to think and feel.

FOMO & FOLS Are Very Real

We’ve written about this before in our essay on the two big psychological drivers for investors. Essentially, the investor’s two biggest psychological drivers are:

- FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) – Investors are constantly afraid of passing on a company that goes on to be a hit, or failing to get in a deal that their competitors got into. This is a big psychological motivation, both for financial reasons (it’s a hit-driven business model so if you miss the big hit, you lose your chance of outsized returns) but also since VC is so competitive. Imagine an investor who saw Facebook or Tesla early on and passed on investing.

- FOLS (Fear of Looking Stupid) – Investors don’t want to look stupid by making an investment in a company that other investors think is an obvious pass. This makes it especially difficult for un-established or less-established VCs to invest in risky companies or in sectors that aren’t very hot because they will look stupid if the company fails. Typically it takes a lot of conviction or a good reputation to make investments like this.

The risk of making stupid-looking mistakes is not just lost upside and the risk of damage to the investor’s brand within the startup ecosystem. It can actually impact the VC’s ability to raise the next fund. As an example, imagine someone investing in a young startup wanting to compete with Facebook when Facebook already had hundreds of millions of users. True, it could work, but given the network effects and momentum of the business, most people would think it’s likely not to, hence the fear of looking stupid becomes a big barrier.

While fundraising, your job is to stoke an investor’s FOMO as much as possible while assuaging their FOLS. The more you can do this, the more successful your fundraising efforts will be.

Additional Resources:

A Counterintuitive Truth About VC Risk

The other big aspect of a VC’s psychology is the desire to reduce risk. When looking at an investment, VCs want to be as sure as they can it’s a great deal. What they really want is to get an un-risky deal at the price of a very risky deal (meaning a low valuation). They want to be as sure as they can that it’s a great deal for them, and so they will ask everyone they can think of about the deal to try and reduce their risk.

This may sound strange: isn’t it the VC’s job to take risks? On the contrary, their job is actually to reduce risk where they can, because startup investing is already so risky. A good way to develop your pitch is to try and anticipate what risks an investor might see in your company and try to address those risks in your pitch.

How To Use VC Psychology To Your Advantage

There are three basic strategies with the highest leverage in your fundraising. If you manage to deploy all three, your chances of successful fundraising go up exponentially.

1. Convince them you are low risk. If you can make your startup seem like a “safe bet” to an investor, it’s going to improve your odds a lot.

Start by learning how VCs see your proof points. We’ve shared several playbooks in our essays “How VCs See Your KPIs” and “The Ladder of Proof.” From there, you can work backward to find the right data points that will communicate your narrative in the best possible way.

Before you’ve launched your product, it can start with non-product proof points like:

- “Our Founders are very experienced and have worked in X top startups.” This communicates that you are not just a strong team but also know how startups move fast and scale from our past experience.

- “We’ve already worked together a few years before founding the company.” This signals to the investor that there’s low team risk, that you know each other well and have proven you can collaborate, etc.

Post product, investors will look for proof points around the different KPIs. For example:

- “We already have 10,000 engaged users who use the app daily” shows retention and engagement.

- “We started monetizing and the conversion to payment is 3%.” This data signals that there’s proven monetization capability and no risk that what you’re building can only be a free app or service.

The more data points you can present to prove you are low risk, the better. And the main thing – as most funding processes take time – is to ensure you provide the updates to the investors that show you are progressing. There’s nothing like fast progress to prove you are low risk.

One last thing on risk: know your competition. Analyze them well. The better you know your competition, the easier it will be to convince investors that you are low risk.

2. Prove you have a huge potential. Remember that VCs need really large exits and that theirs is a hits-driven business. To get them interested, you have to be able to paint an ambitious but credible vision about how your company could end up being transformative.

How do you prove your potential? Numbers play a big part. Master understanding your TAM and SAM and come prepared with the data. Nobody believes you can take 50% of your market, so ensure that even if you’re talking about 5% that you have a huge story to tell.

Using references from other industries can be helpful to illustrate your point: “the SaaS platform for this vertical created a multi-billion $ business, the vertical we are after is a similar size, so we can build a similar-sized business.”

Present your potential not just from a top-down perspective, but also bottom-up: for example, “we aim to capture 5% of the industry’s IT spend. Bottom-up, this means that we will need 10% of the potential customers to pay us $1k/month, which makes sense.”

When you lock down the numbers both bottom-up and top-down, your story becomes a lot more credible. Do the numbers have to be precise? Not really. Nobody expects your numbers to be accurate looking years ahead. But remember: if you project only $5M revenues after 5 years, you are usually not interesting for a VC. The VC isn’t questioning whether you can be a $5-6M business, they’re questioning whether you can be a $100M revenue business.

3. Show them other investors are interested. Leverage is key when it comes to negotiation, and fundraising is no different. For example, if you’re meeting with other funds, saying that you’re in “partner meeting discussion at X fund” or in “advance discussions at X fund” will trigger FOMO. The ultimate FOMO sentence, however: “I have a term sheet that I need to decide on quickly.”

Just like anyone else, VCs are also influenced by their peers. So the fact that someone else is advancing the process of investment not only applies time pressure and forces the investor to move quickly, but also makes you look more attractive and less risky.

A term sheet or even the signs of progress with a top fund will get other funds to feel you are a lot more attractive. So communicate your progress wisely.

Two important points on this:

- Never lie. Ever. Eventually, everything will come out.

- Be careful with transparency. You usually don’t want your potential investors talking to each other (unless they come as a group of course) so don’t share the specific identity of other firms.

If you manage to master all 3: convincing VCs you are low risk, have high potential, and that others are interested, your chances of funding will skyrocket.

Additional Resources:

A Quick Note On Angel Investors

Other than VCs, angel investors are another common source of funding, especially for startups in the earliest stages (seed or pre-seed).

Angels can be a great option, both as standalone investors or as part of a VC round. The best angel investors can be a real asset for your company. They’re similar to VCs, but there are important differences: they tend to invest lower amounts, and can sometimes be more open to businesses with more modest TAMs as they don’t have to worry about returning a fund or clearing a hurdle rate. But don’t mistake them as “small” – many angel investors are powerfully influential and have huge networks.

Therefore, it’s sometimes better to meet with angels before VCs as they can be more friendly, the decision process for them is simpler, and there is no partnership to convince (just one person). Although they can also change their mind without clear reasons just like VCs, an angel investor with a good reputation committing to your round can go a long way with VCs.

The 7 Phases of Fundraising

Everyone’s fundraising experience is unique, but there are common processes that lead to success. Below we’ve provided a 7-step detailed template to help you maximize your efficiency, preparation, and learning as you fundraise.

Phase 1: Make A Target Investor List

Think of this list like a personal CRM of your fundraising efforts. It will help you plan throughout your fundraising so that you can maintain efficiency and focus.

This will help you avoid choosing the wrong VCs (ones who are not investing in your stage, geography, or field), which will only waste your time. It will also prevent you from choosing the wrong VC partner, which could dramatically reduce the chance of raising from that firm. Once one partner says no, it is very rare that another partner in the same fund will engage before some time passes and the company has more proof points.

So put the time into your preliminary research, and make sure you have a great list of the funds and the specific partners you are planning to engage with.

Who should be on your target list? VC firms that are:

- Focused on your stage, or your business type, your geography, and are interested in your problem.

- Known to give simple deal terms, and have good reputations.

NFX’s fundraising platform Signal has 10k+ investor profiles and counting is a good place to find VCs interested in companies in your stage and sector. Once you have your list of target funds, it’s time to choose a specific partner to target before you reach out.

Also, speaking to fellow founders and getting their recommendations on investors they think are relevant for you is another great source of information for building your target list.

When building your list, be sure to consider that:

a) Each partner has a different taste and focus.

b) To suss out a potential match, you can try talking to other Founders the target partner has invested in.

The last step in completing your target list is to rule out VCs with competing portfolio companies. This is an important but often overlooked step that will save you a lot of time and wasted effort.

Why these VCs are not desirable is because they’re less likely to invest in you if they’ve already invested in your competitors. What’s more, they may share some data you give them with your competitor. They might even take a meeting with you for that reason, even if they have no intention of investing.

In most cases, they’ll ‘ask’ the current portfolio company if they care that they invest in you. They almost always do care, so your chances are low to start with. Unless you have no choice, it’s smart to try to avoid such conflicts of interest by taking such VCs off your target list entirely.

At the end of this stage, you will have a list of at least 20 (but preferably closer to 50) target VCs with the identified preferred partner in each one of them. For each one, it’s also wise to have a backup preferred partner in case you can’t get a warm intro to your first choice. You are now ready to start the process.

Phase 2: Fill Your Meeting Pipeline

You’ll want to manage the process of reaching out with the Target Investor List you built in phase one. Here’s a sample list we’ve built as a template.

Within that list, create an investors sheet that is shared with all the people who can refer you (or use Signal).

- Include columns for the investor’s name, firm, status, owner (the person in charge of introducing you to this investor), key objections, notes, next action items, and reminders of actions you need to take.

- Update this document daily and chase “owners” for the intros.

- This CRM spreadsheet is the main tool you will be using to drive the process forward. Not updating it, or managing it improperly reduces your chances of successfully fundraising.

- Some teams prefer to use a CRM tool like Hubspot. Others find that tools like Notion work for them better. The truth is that all of these work as long as you conduct your research well and keep the data updated.

Motivating An Investor To Take A Meeting With You

There are 5 things that will typically motivate a VC partner on your target list to take a meeting:

- A warm intro from someone they trust. This is by far the best way to get a meeting.

- Hearing that a competitor is seriously looking at the deal (i.e. competitive momentum).

- KPIs: Seeing that you’re growing really quickly.

- And other key KPIs can motivate VCs to take a meeting.

- Bonus: The X Factor — they’re intrigued by something unique about you that catches their attention. But this is tough to predict or engineer, and it can backfire if you try to be intriguing on purpose.

Review the Ladder of Proof for additional proof points that VCs look for so that you can present them accordingly. Put yourself in the investor’s shoes: what is it about your company in its current state that can convince an investor that it’s an opportunity they must look at? If you can’t find the reason, neither will they.

The best entry path is to use your network to try and get warm intros. The reality is that most VC deals originate from warm intros. A warm intro is 100x more effective than a cold email.

Remember that everyone can be your referrer — including your early investors, advisors, friends, customers… anyone who can potentially serve as a bridge in the network. But also know that investors will weigh different referrers differently — so 1-2 great referrers is better than 10 average referrers. A warm intro with a recommendation from a successful founder to an investor they know well, for example, will almost always lead to a meeting.

Be persistent in pursuing these intros— it’s not a time to be shy! (A helpful tip here: being grateful and saying thank you is a great way to combat your resistance to asking for “help” or “favors” which most people misinterpret as shyness).

At the end of this stage, you will have an intro path to each target investor on your list and you will be ready to start taking the meetings.

12 Reasons VCs Decide To Take A First Meeting

At this stage, we recommend that you review our essay on the 12 Reasons VCs Decide To Take A First Meeting, which will familiarize you with the criteria investors are screening for. Here’s an overview:

1. Team Excellence – Can you demonstrate the quality of your team using past successes?

2. Company Description – Are you nailing your short pitch/ one-liner? A really good one-liner is a huge asset.

3. Market – Can you show a compelling line of reasoning about your market opportunity?

4. Business model – How do you make money? Who pays? What are the margins?

5. Geography – Where is the team located? Investors will often have a preference.

6. Number of employees – How big is your team?

7. Timing – Why is now the right timing for your company?

8. Traction – What traction metrics can best demonstrate what you’ve already achieved?

9. Fundraising amount – How much are you targeting to raise?

10. Fundraising history – Who have you raised from, how much, and when?

11. Investor fit – What about the particular investor/firm makes you want to meet with them?

12. Referrer quality – Who introduced you to the VC and how trusted are they?

3 Types Of Intro Emails

While we strongly recommend focusing on getting warm introductions to investors, eventually you may still need to send some cold emails. When you do so, there are basically three types:

- Generic emails – It’s very clear that the Founder has sent the same email to 50 other investors. Typically won’t be opened.

- Superficially personalized emails – The Founder has made some effort to personalize the email to the investor, but it’s clearly superficial.

- Deeply personalized emails – the Founder dives deep in a way that speaks specifically and uniquely to the investor being addressed.

As an investor, of these 3 types of cold emails, the third is most likely to succeed. The more the investor can see that you conducted your research and the more you can provide your reasoning as to why this a good opportunity for them, the better chances you have for the investor to take the meeting.

Plan Your Fundraising Sequence

As you begin to get introductions, the next thing to be mindful of is that you need to be intentional about the order of meetings. Meet a few (5 is a good sample number) less relevant investors first to train yourself and level up your fundraising skills without the risk of losing a highly desired investor. Learn from these meetings, improve your pitch and use them to prepare for meeting higher-priority investors down the line.

Once you feel more comfortable with your fundraising skills and pitch, go for investors who are relevant but are lower-tier and more likely to engage. This will help build your confidence. Finally, try to get meetings with the top-tier VCs after training your fundraising skills and getting positive signals from others. These signals from others will also put you in a stronger position going into the top tier funds you want most.

Drive the Timing

Once you’re ready to meet with VCs (after test pitches), you may reach out all at once. Timeboxing works in your favor.

Decide on an objective date for each phase that you can refer to (i.e. the first meetings will be done by X date — this creates momentum and feeds into FOMO).

The immediate goal is to get a first credible term sheet from anyone. This will drive speed of decision for other investors more than anything else. As an interim step, you can focus on getting second meetings and later on getting invited into partner meetings.

Additional Resources:

Phase 3: Build a Strong Pitch Deck

The first thing to understand is there are multiple pitch decks. There’s the intro pitch deck, which you send to try to get the meeting. Then there’s the 1st meeting pitch deck, then the 2nd meeting, then the partnership meeting pitch deck, etc. In addition to that, you want to really customize each pitch deck for each investor. So, you’ll want to get very, very good at decks.

For now, let’s focus on your intro or 1st meeting pitch deck.

We may be different from other investors, but we really like getting short and to the point decks. And the quality of the deck is also very important. If I see mistakes, I’m going to be asking myself: Is this team going to make these mistakes when they go out to customers? If it’s too long, like 70 slides, I’m going to be worried that you don’t have good judgment about what’s important. Don’t act like the COO and obsess over the details of your company in these first meeting pitch decks. You’re the CEO. If you can’t tell the full story of your company in 5-10 minutes, you’re either overthinking it or you need to be a clearer storyteller.

Elements of an Unusually Great Pitch Deck

15 great looking slides:

1. Introduction / Cover Page

2. Team (context, why they’re great, holes that you need to fill)

3. Problem (Why it’s a painkiller, not a vitamin)

4. Your Vision (Why it’s big, why now, what’s your product going to be?)

5. Size of the opportunity (TAM from a bottom-up perspective)

6. Business model (unit economics + how you make $)

7. Traction metrics (what’s your market validation, KPIs?)

8. Product (including a demo + description of why it’s great)

9. Competition (history of the space, complete market map, how you’re different)

10. Path to defensibility ( how you’ll build defensibility/network effects)

11. What’s your plan ahead? (Roadmap, financials and hiring, org chart, Funding, use of cash, and runway projections)

12. Distribution (Initial target customer & channel for customer acquisition)

13. Secret sauce, key insights

14. Summary of the strongest points in the deck

15. Appendix – tough questions + data

- Every slide should have a single title or headline. The headline must be the message you want them to remember. So a title that says ‘Market size’ means nothing, but a headline that says ‘$10bn market with an immediate $2bn SAM’ leaves the investor with a concrete and memorable piece of information.

- Include your metrics. The more you can convince the investors with data, the better.

- Must have good competitive analysis, including a good market map.

- Focus on business defensibility and why it can be huge.

- Include an appendix with slides for every question you can predict. You will probably start your journey with only a couple of appendix slides but should have at least 10 different ones to address frequently asked questions by the time you finish the process.

For a full sample pitch deck, click here.

4 Key Elements Of Your Financial Model

Another big part of your pitch presentation should be your financial model, which should include 4 big things:

- Include 24 months modeled monthly and another 3 years modeled annually (if credible).

- Have clear assumptions the VC can understand. Each line should tell a story. Obviously, nobody expects your predictions for Year 3 to be very precise; however, the model helps them understand how you think, which is the important thing. They want to see how aggressive you are; how you think about salaries and costs, whether you understand the business model well (for example, in a B2B business what sales performance are you expecting from each salesperson you are adding). The clearer and better the assumptions you are using for the model are, the more trust you will build with the investors.

- Requested investment should provide at least 18-24 months of runway. No investor wants to invest in a company that immediately needs to go out and raise capital again. You will need to say how much you want to raise, and generally, it’s better for this to be lower than your maximum desired amount, as this makes the ask more reasonable and it’s always easy to increase the sum if you are oversubscribed.

- Show size of revenue opportunity using TAM (# of customers * annual revenue per customer). Go global if the US revenue opportunity is less than $2B. Note that this TAM calculation is more important than a 5-year revenue projection, as VCs know you probably won’t be precise in your 5-year plan.

Note that it’s better to be conservative than naive with your financial model. It’s also important to have multiple financial plans. Having one plan is not enough because different investors will want to invest different amounts, and you need to be prepared.

So you’ll need 2-3 plans based on how much you raise. For example, there’s a $1M plan, $3M plan, and a $5M plan. You can’t use the same plan for each amount; more money is not supposed to simply last longer. You should spend it faster to achieve faster growth.

You should have your main model and fundraising goal and mostly stick to it, but if an investor asks you ‘what can you do with more capital?’ you must be ready. Also, sometimes you will take investor meetings with people who invest amounts that are too small or too large for your target raise, and you should have a relevant plan for them.

Once you have your deck and financial model (which is also presented in a slide in the deck) – you are ready to go.

Remember The Pre-Meeting Materials

Once your decks and financial models are ready, the next thing is to prepare is your pre-meeting material. Some VCs will require you to pre-send them material. Almost all will want you to leave materials with them. Materials go to other partners, associates, and analysts and should be fairly self-explanatory.

If your deck can’t be understood without someone presenting it, other VC partners that aren’t present in your meeting will not be able to understand it and you will miss the opportunity to excite them once the partner you met sends it to them.

Be aware that VCs are likely to share your materials with industry experts and even their portfolio companies as part of their process, looking to gather more opinions. They may ask your permission, but many times will not. If you want them not to share it with someone specific, make sure and say so.

Also if you feel you have a big secret which you don’t want to be shared, just don’t put it in the deck or your other materials, though you can still of course mention it in the meeting. Some founders ask VCs to sign NDAs, but that’s very uncommon and would present you as someone who does not know the industry well, as VCs hardly ever sign NDAs.

In addition to your deck, the pre-meeting material will often include an executive summary which should be a one-page max, short description of the problem, opportunity, product, status of your company, and team. Don’t turn this into a full presentation in a tiny font. It should be skimmable in a few minutes. It is meant to get attention and remind investors who they are about to meet.

Phase 4: Prepare for the Meeting

Once everything is in place, you’ll want to prepare for each specific meeting before it happens.

Research the specific partner you’re meeting with. Know their other investments, big wins and losses, interviewing style (if possible from other Founders), people they’re connected to, their social media habits. Know what they posted on Twitter that day. If they’ve written blogs or essays, read them.

Also, learn about the entire fund. Know their portfolio companies, big wins, and losses, details about the other partners including their tweets and blog posts.

Adjust your story to the fund and specific partner. Don’t try to educate investors on a field they don’t naturally like, and be sensitive when discussing past and current investments. This may seem like a lot of work as preparation for a meeting, but remember that you are one company out of hundreds pitching the partner. To get to the finish line successfully you need every edge you can get.

You will be surprised how a wrong comment about their portfolio company or not being prepared for their question-asking style can impact the outcome of a meeting.

16 Lessons For Successful Pitching

Before taking your first meeting, be sure to review our essay and video on 16 lessons for pitching. Some of the biggest takeaways are:

- Don’t say sentences that don’t have numbers in them. Talk in specific numbers, not in generalities.

- Jump to the screen and point… Present with energy. Talk while standing at the whiteboard, or standing pointing at a slide. Move around the room. If you’re pitching remotely, use these tips from top-tier VCs.

- Diagrams communicate 10x more. Using visual tools to get your point across sharpens the conversation and increases the information density of your pitch.

- Send your Company Brief ahead of time with your other pre-meeting material. That way when you get to the meeting, you can actually get to the heart of their concerns and interests in your business. Otherwise, you’re going to spend the first 20 minutes going over the basics.

- Don’t talk about your passion — show it. Project your passion during your pitch. Show that you’re a full-blooded person that’s going to drive the business forward through strength of will.

- Look the part. Wear something nice, sharp, crisp, and that shows you’re serious about being a professional. Even on Zoom.

- Only bring your best presenters. Everybody that you bring to that room needs to be as compelling as you are, everyone needs to have a role to play in the pitch, or they should not be in the room.

- Spend 1/3 presenting, 2/3 asking questions. Leave the majority of your time for questions and discussion. Review our list of 40+ questions to ask investors in fundraising meetings, and have appendix slides ready as backups when answering questions. This helps you reply crisply and shows you’re prepared.

Also, during the meeting, you should know your competition and demonstrate that knowledge. Memorize the competitive landscape and be their guide through the jungle of your market sector. If you are asked about a competitor and need to look it up to explain how they differ or even worse you never heard of them, your chances of fundraising just went down dramatically.

If others are going into the meeting with you, decide who speaks when beforehand and make sure that everyone there plays a part. Some teams prefer splitting the slides between them, others will let the CEO do the entire pitch and let the team members take the more detailed questions. Both routes are ok as long as everyone gets their chance of speaking.

When others speak, make sure you never contradict or disrupt each other, because the VCs will be paying attention to your team dynamics. Make the CEO the quarterback who hands over questions to each other team members so that no one jumps to answer questions they are not supposed to.

Again, you should rehearse your pitch presentation to the point of fluency. Rehearse presenting while being stopped by questions, which will likely happen. Be prepared to reply to the questions and move forward with the presentation without losing focus and momentum. It is very likely you will not be given 15 quiet minutes to pitch with no interruption (and if you get it, be worried that your audience is not engaged!) so learn how to take the questions and get the pitch back on track.

Finally, never let a meeting end before you find out where you stand by asking questions like:

- What’s the process from here?

- Do you need any more info from me?

- Do we need another meeting? When?

- And if you do get a positive indication: Do I need to meet the other partners?

Getting out with action items is a great tool to keep the conversation alive and ongoing. If you promise to send more information or further analysis, you have the justification for the next round of communication with the partner.

How do you know if the meeting went well? You won’t always know for sure. Some VCs are confrontational; others would prefer to be nice and give the ‘no’ later in an email.

Generally, if you didn’t get hard questions, they are not interested. If they cut the meeting short, they are not interested.

On the other hand, if you got lots of hard questions and they extended the meeting beyond the set time, these are good signals. But the only real positive indication is if they talk about the timeline and next steps.

In the meeting itself, another priority should be to present yourself in a way that demonstrates the right character.

VCs judge your character in the meeting and the way you interact with them. Leaving the right impression of your character is critical for getting a deal done. Investors won’t invest in people they don’t like. Be the person you would like to invest in if you were the VC.

5 EQ Traits Of Great Founders During Fundraising

- Be transparent and honest. Investors will not invest if they pick up signals of lack of transparency or honesty. This is part of the risks that they’re trying to reduce. Be careful with games (like “round closes today”) or small exaggerations (like “we have a meeting with a senior partner” at a fund where you’re about to meet with an associate). Don’t be afraid to admit what you don’t know.

- Show speed and commitment: Return emails fast, provide requested data immediately, be persistent during the fundraising process, and be available to physically meet if possible.

- Show seriousness and professionalism. Answer questions seriously, and provide the research you conducted when relevant. Make sure everything you deliver leaves a great impression.

- Be calm. Accept all questions with love. Don’t complain about the process — if you don’t like it, disengage. Don’t tell them what you think about the process. Be nice when you get rejected, because it could matter when you meet them again.

- Don’t be arrogant. This can happen when things are going well, but it’s important to stay grounded and be nice. Remember that all startups have ups and downs, and you will need the investors tomorrow.

Once you finish a meeting, remember the learning cycle and try to change at least one thing in your deck and pitch. You must get better for the next one! This means also understanding why you got rejections. If the investor is not clear or didn’t share why, ask politely. The honest opinion of a VC that just rejected you can lead to the change in your pitch that will eventually get you funded.

Additional Resources:

- The Winning Psychology of top Founders in Fundraising Meetings

- How VCs Judge Your Startup (on Zoom): 15+ Tactics Behind Successful Fundraises

Phase 5: Create and Maintain Momentum

Remember that time is the VCs friend and your enemy.

For the VC, more time allows them to see how the business progresses and what others think before committing, to conduct more due diligence, get more opinions, and generally de-risk the deal.

For you, more time means less money to work and higher chances of the VC getting cold feet. So your goal is to close fast.

Closing depends on creating and maintaining momentum. Momentum can be both momentum in the fundraising process but also progress in the business. Here are some examples of momentum:

- Progress with other firms, whether to a second partner meeting, a full partnership meeting, or getting a term sheet. With this, what you are actually telling the investor is “others are interested, you want to be in. If you move slowly you are out.” This is the only reason for a VC to really move fast.

- Progress with your business: you are moving up on the Ladder of Proof, e.g. more high-quality employees, more customers, more users, more revenues — anything that makes the VC feel that your business is doing well and moving fast. The faster the VC thinks the business is moving, the less risky it seems, and the more pressure on the investor to move fast.

The 1st term sheet is your critical step – once you have it others must move faster. In reality, it’s almost not important who the term sheet is from. Preferably the terms are decent so you can actually sign it if you need to, but even terms you don’t plan to accept allow you to genuinely share that you got a term sheet that you are considering.

Given the importance of the first term sheet, it sometimes makes sense to focus on the investors that you feel are closest to giving you a term sheet and finding out what it would take them to cross the line. Once you have it, gently let others know. Don’t reveal who else is in the process, but share that the process is moving forward in order to increase FOMO.

Advice For Following Up After A Meeting

How do you maintain momentum? By creating the right flow of communication and updates.

- Always write a thank you email after the meeting. In the email, make sure to tackle the points you felt were left open.

- Always offer to provide more information and don’t forget to ask about the next steps.

- If you promised to provide any additional information, send it as soon as you can with an email explaining exactly what you are sending.

- Whenever you have progressed to a new milestone in your business, update the investors who are still in the process of deliberating.

- When you get a term sheet, update investors who are still in the process.

Above all, keep the flow of information going to ensure you keep momentum.

Phase 6: Understand the Deal

Once you start getting offers, you need to understand your deal before you sign a term sheet. Here are the biggest things you need to know.

Types of Equity

You can either raise equity or use a convertible note (SAFE or CLA). Pre-series A rounds tend to be mostly convertibles, while SAFE is a simpler option and the preferred route. Series A onwards will mostly be priced.

Normal terms for convertibles include up to a 20% discount (ranging from 10%-30%, sometimes steps based on time-to-funding, which is not recommended). In most rounds today there will be a valuation cap.

Important Deal Attributes

Here’s what is most important about the deal for your fundraising to be successful.

- Contrary to what you might think, valuation is not the most important thing.

- Getting the funding done quickly is just as important. Every day you spend fundraising is a day lost towards building a winning business.

- Next is finding great investors who will be your partner for years.

- Other terms could be more material than the valuation, especially if an investor is asking for aggressive terms like full preference in an early-round or veto rights that will impact normal operations.

Valuation is important only after you work out all the rest. Be aware, also, that too high a valuation creates problems for subsequent rounds, i.e. your investors are likely to expect a 3x bump in valuation in the subsequent round, and if you start too high, you may end up disappointing your investors or having to try to raise at an unrealistic valuation down the line

In general, you need to balance all the factors above to choose the best combination. Your most desired investor is likely to come in with a lower valuation than someone who is not as great and needs to pay more to win deals as a result. But getting a bad investor who will slow you down, or being slow in fundraising and losing time in building your business may not be worth the higher valuation. Weigh all factors, consult with people you trust and try your best to find the best balance.

Deal Duration

For series A and later fundraising rounds, a round is usually a single process led by a “lead investor” that closes simultaneously for all investors participating in the round. Earlier rounds today can be an ongoing process over a long period, with money flowing in over time, usually in a SAFE form. In general, prefer to fill the entirety of the round so you can stop fundraising and start building; however, if you can close a part of the round faster and start hiring, you might want to consider doing so.

Cap Tables

Finally, you must have a well-prepared cap table you understand well. Avoid the common cap table pitfalls, which include:

- Too little equity for Founders due to dilution. A typical round dilution is 25-33% and you should aim for that range.

- The right ESOP amount. This amount depends on the number of people you need to recruit, the stage of the company, and the roles covered by the founders. A team of 4 founders covering tech, product, business, and operations may justify a lower ESOP allocation compared to a single product founder who will need to recruit senior people for the other roles. Typically, seed-stage ESOP is 10-15% after the round, and Series A post-round required ESOP is 7-10%.

- A significant amount of open CLAs/SAFEs. Avoid situations where you ‘stack’ convertible documents. This stacking sometimes creates cluttered cap tables, which may lead to lots of debates on how the convertible of the different-prices convertibles should be calculated, and eventually strains your subsequent equity round. As a rule of thumb, try to never have more than two ‘open’ (not yet converted to equity) convertible rounds.

- Too many preferred shares at an early stage. The standard for seed deals (if it’s equity funding and not a SAFE) is for common or non-participating preferred shares.

As a general rule of thumb with cap tables: try to finish your seed stage with less than 30% owed to investors.

Phase 7: Be Strategic As You Negotiate

We’ve written before about how to level up your negotiation ability by mastering these 8 skills. This is what we at NFX call “high leverage fundraising” – it gives you speed & clarity, while still helping cultivate strong, long-term relationships.

You should be aware of the most common VC negotiation tactics and how you can respond to them.

Common VC Tactic #1 – Asking you to name the price

What the VC will say:

VCs will often ask Founders to “name their price.” This is a fair question for the VC, who will not pay more than they think the company should be valued at in any case. But Founders who are afraid to look too aggressive will often name a low valuation, thinking this means fewer price negotiations. In reality, the low valuation becomes the starting point of the negotiation.

How to Reply:

The best way to approach this situation (unless, of course, the negotiation is an extension of an existing round or a note that already has a set price) is to politely say: “We don’t know yet. We will let the market set the price.” If you had a previous round, share any relevant information about that round at this point in the conversation. Include any notes that could help set the tone of the current round versus the previous one.

For example: “Our post-money valuation of the previous round was $8M and we made progress: our revenues grew by 80%. We will let the market set the price.”

Common VC Tactic #2 – Lowballing you upfront

What the VC will say:

VCs often “lowball” Founders during startup fundraising. Sometimes it’s a sign of a bad VC but more often than not, it’s simply the starting point of a negotiation. Many inexperienced Founders don’t realize this, and they get flustered. This can lead to the deal going sour, and dying – even though it doesn’t have to.

How to Reply:

First, manage your emotions and don’t be insulted! This is a dance and you know the moves as well. Thank the VC for the offer, let them know you think the offer is low, and then simply slow down the process. You always want to keep the offer as a backup so you can truthfully tell other VCs that you are in discussions with others. When you see you have interest at a reasonable price, get in touch with the lowballer VC, apologize, and say that another offer came in at a much higher price. The VC may then suddenly be open to a higher valuation.

For example: “Thanks for the offer. This is dramatically lower than what we had in mind but let us get back to you.”Then, once you have interest: “Sorry it took us time to get back to you, but we were getting offers from other VCs at a much higher valuation range. We understand this may not be right for you–let us know if you want to discuss.” Always keep your cool! Remember, keeping strong connections with VCs may serve you well the next time you’re fundraising.

Common VC Tactic #3 – Being nice at the meeting only to lowball you later

What the VC will say:

Knowing what to expect is half of the game. Sometimes, when a VC is friendly and supportive in the meeting, it leaves Founders feeling like they will get a strong valuation – even though no valuation was discussed. Later, if a lowball offer comes in, the Founder feels they were just handed a “lowball curveball.” Now in a very emotional state, Founders tend to accept a lowball curveball more often than a standard lowball, convincing themselves that if the valuation came from someone so friendly it must be the right one.

How to Reply:

Friendliness is often sincere, but it’s important not to confuse liking the VC with agreeing with their valuation. The key here is this: don’t get swept up in emotion. You are likely to overestimate how enthusiastic a VC really is about the deal, so don’t be surprised by a lowball curveball.

For example: “Thanks for the offer. We also loved the meeting and felt we could work well together. But this valuation is just so low that it seems outside of the market. Let us think about it and get back to you. We would of course love finding a way to work together!”

Common VC Tactic #4 – A conditional “yes”

What the VC will say:

It is important to understand that when VCs meet a good team, they have no reason to stop the discussions, even if they can’t make up their mind on whether to invest. VCs almost always prefer to stay in the loop and keep their options open, rather than giving an outright “no.” It’s possible that a top fund could take the lead, and that could make the VC want to jump in. How do they do this? One way is that they “commit” but with certain contingencies, like the Founders having to “find the lead” or “bring the rest of the money first.” What a VC is actually communicating is, “I like what you’re doing, but not enough to lead.”

How to Reply:

Learn the language and know that the VC just said “maybe”, at most. Do your best to get the investors to commit to putting their money in without any contingencies. And give lower priority to those who “don’t lead” (By the way, not leading is usually just an excuse – most VCs, aside from some later stage investors, lead a round when they are super excited about the deal.)

At the same time, you do not want to push the VC away. The message that you have follow-on investors lined up could be beneficial when you talk to your potential leads.

For example: “Thanks for believing in us! We are now indeed focused on finding our lead and will be in touch when we do. Hopefully, once we find the lead we will still have room in the round.” Or in other words: if you want to secure your participation, you have to commit NOW.

Common VC Tactic #5 – Asking you to talk to a portfolio company

What the VC will say:

A VC will sometimes ask Founders to meet with one of their portfolio companies in the same space/vertical so they can get their POV. This is usually a lose-lose situation. As a Founder, you don’t want to share your plans with a company so close to your space, and the portfolio company is likely to prefer that the VC not invest in another company in their space.

9 times out of 10 the existing Founders will tell the VC, “yes we are thinking of going into that business someday so please don’t invest in them.” Once the VC has that very conversation with the portfolio Founders, it’s VERY hard for the VC to override them and invest in you. The existing Founders have no incentive to let their VC invest. No upside, only downside. So the behavior is understandable, but a pain for you. And it’s part of the trap of a portfolio check. For VCs, this can be a heartfelt attempt to make a good decision or, in a bad scenario, an attempt to educate their portfolio company.

How to Reply:

If the portfolio company is too close to your business, explain to the VC that you are not comfortable discussing your company with them. For example: “I would be happy to meet anyone you want in general, but this company is just too close to our business to feel comfortable. Maybe there are other industry experts you would like us to meet instead?”

If the portfolio company isn’t a threat to your business, then meet the Founders and get a sense of what their experience has been like working with the investor–take advantage of the opportunity.

Common VC Tactic #6 – An offer with a short deadline (‘i.e. exploding term sheet’)

What the VC will say:

We at NFX don’t really like “exploding term sheets” that expire after just a few days. Simply put, healthy Founder-VC communication can overcome the need for such mechanisms. However, Founders sometimes drag the fundraising process beyond a reasonable period of time in hopes of getting more term sheets. As such, exploding term sheets and term sheet deadlines have become very common.

Normal deadlines are around one week, giving the Founders enough time to review their options and decide. But we’ve seen VCs (even good ones) give Founders much shorter deadlines, even as little as one day. This doesn’t let Founders appropriately evaluate their options and often leads to suboptimal deals. Adding insult to injury, short deadlines are often accompanied by a lowball offer.

How to Reply:

A deadline is ok if it’s normal (around a week). If the investor is not willing to give you a week, consider your situation, but it’s ok to push back. Generally, a short deadline may mean the investor wants the deal and is worried you will get additional offers. Make an effort to get additional offers. Once you do, it gives you a stronger hand in pushing back on the deadline.

Remember that you are entering a very long-term relationship here, which is supposed to be with people you can trust and enjoy working with. Ask yourself whether you want a partner who is so aggressive at the first interaction. Next, ask for an extension. If the VC isn’t willing to give you a reasonable amount of time (at least a few days) to consider your situation, it’s ok to push back. Here’s the truth: if a VC really likes your business and your team, she/he is unlikely to not invest because of a day or two. Just as you are likely to be wrong about how excited an investor really is about your company, you are likely to misjudge how long it takes to close an investment and the investor’s real red lines.

In any case, there’s no need to disengage with the VC because of the unfair deadline. Play the game and get back to the VC in the final moments of the deadline to say that you need more time. Always have the option on your side. Another tactic is to delay the deadline by asking the investor for something that will take time. For example: “Thanks for the term sheet, but we just don’t think we can sign it within 24 hours-we need to review our options and also consult with a few people. Also, before we proceed, can you please provide us with a few Founders you invested in that we can chat with?”

Common VC Tactic #7 – Asking for an excessive ESOP allocation

What the VC will say:

Sometimes VCs will ask for an excessive ESOP allocation. It’s in a VC’s interest to have as much ESOP as possible allocated before the round because it means less future dilution for the VC. Remember, part of the job in VC is to de-risk investments as much as possible.

Furthermore, in an early exit scenario the unallocated ESOP benefits all shareholders–not just the Founders who are the ones diluted from the pre-round ESOP allocation. While every round has an ESOP allocation (or top-up in case of a later round), the numbers vary dramatically. And it isn’t unheard of for a VC to ask for 20% ESOP, sometimes even more. Also remember that to get to 10% ESOP post-round where the dilution is, say, 25%, you actually need 13 ⅓ % ESOP before the round as the ESOP is also diluted by the round.

How to Reply:

First, know the market standard. 10-15% available ESOP post-round is common for seed deals. 7.5-10% ESOP is common for A rounds.

Then show the ESOP requirements you’ll need until your next round – that’s the amount the VC should care about and push for. Keep in mind that the more complete your team is, the less ESOP you’ll need. Be clear about whether you are talking pre-round or post-round numbers. Again here, the VC is likely to talk in post-round numbers.

For example (seed deal): “We are 3 Founders who cover between us product, tech, and sales. We need a CMO and have already found the person. Getting him/her requires 2% ESOP. For the rest of the team, our plan shows we’ll need an additional 5% ESOP for the coming 18 months, which brings us to 7% total. We, therefore, think that 10% ESOP post-round is enough.”

One last piece of advice: don’t relax until the money is in the bank! Energy, interest, and even compliments from VCs mean nothing. Verbal assurances a deal will get done is also nothing. A signed term sheet is still not enough. Even a definitive agreement signed is still not enough. Your goal is money in the bank. Money that you can spend on your company and team in order to move as quickly as possible to change the most lives with your product. Don’t rest until you achieve that goal.

A Closing Note (For Now)

At NFX we’ve all been Founders many times over. We’ve been in your shoes and want to give you every competitive advantage in mastering the fundraising process.

That’s why we wrote this guide and developed Founder-friendly tools like Signal and The Brief. Though fundraising is mission-critical to building a transformational company, it shouldn’t be a barrier to your potential success. The startup ecosystem only benefits with lower friction and more access.