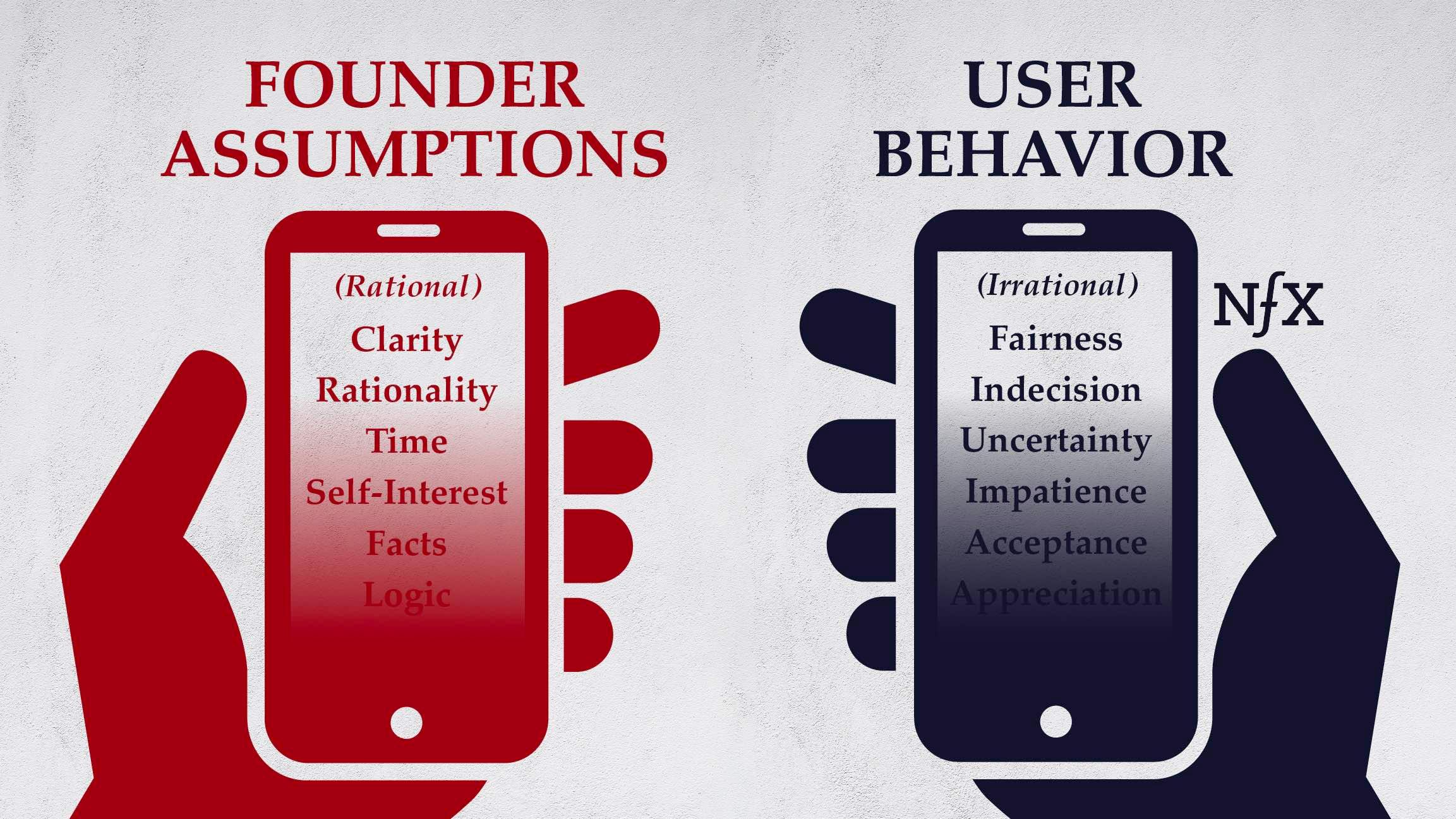

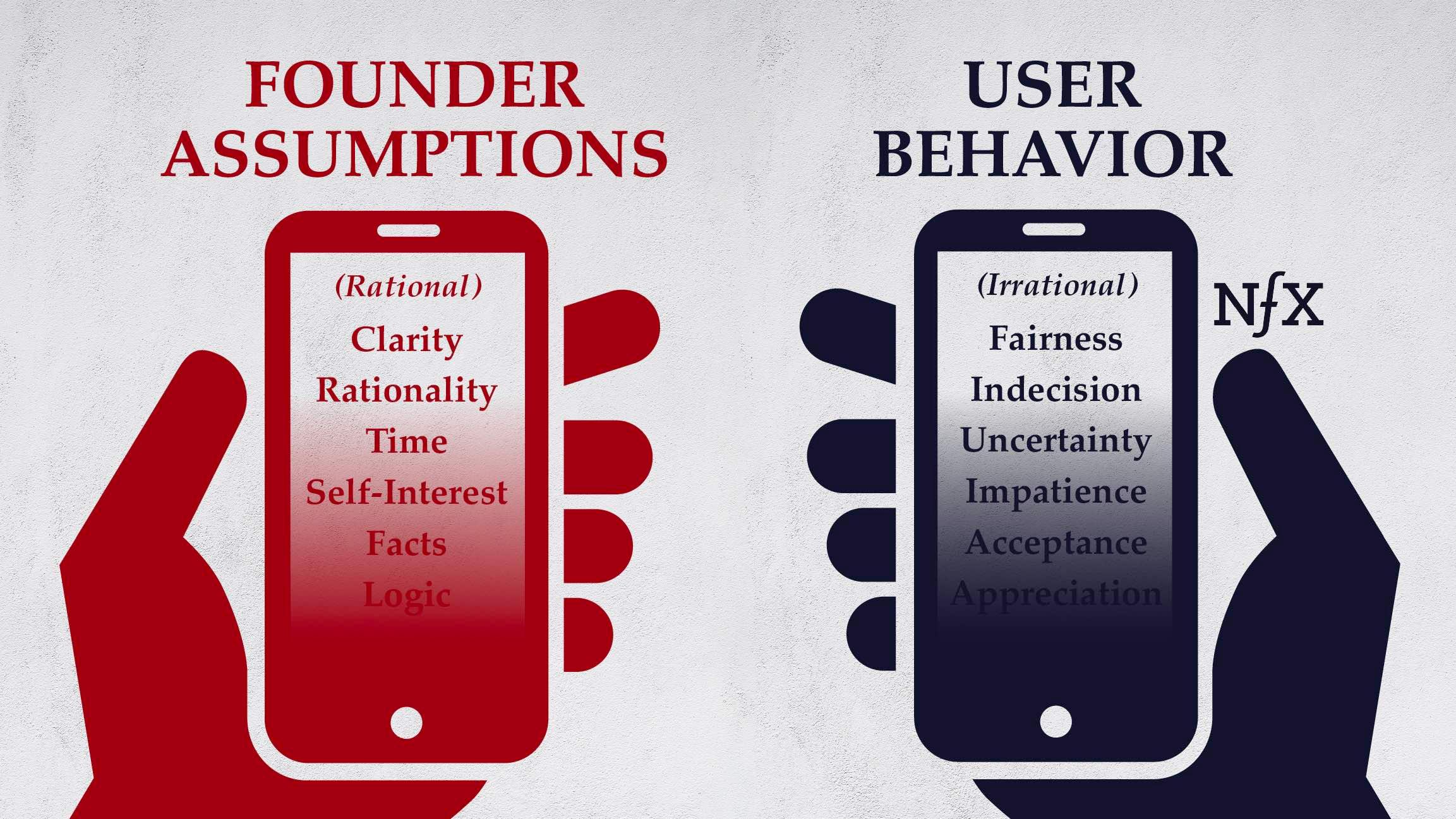

We all think we know how our users behave. It turns out, we don’t.

Founders must accept that we all have a “curse of knowledge” — we know our own products so well that we end up making rational assumptions about what our users want that are just not true.

Behavioral economics, by contrast, is the practice of truly seeing your users’ (often irrational) emotions, beliefs, and habits.

In my recent analysis with Dan Ariely — the world’s top expert in behavioral economics and a renowned professor at Duke — he breaks down the most common types of irrational user behavior and shares frameworks for designing for how your users will actually behave.

The questions Founders need to ask themselves, as early on in their startups as possible, are:

- How can I see, more clearly, the irrational nature of my customers?

- How can I design products (and acquisition, conversion, pricing & retention methodologies) to leverage these predictably irrational scenarios into runaway growth?

At NFX, we often say that understanding psychology is one of your highest leverage points for building iconic companies. Founders who understand the true motivations of their users — and adopt frameworks to “anti-pattern” their rational assumptions — will be stronger at building products that define our future.

SECTION ONE: People Behave Very Differently From What You Expect

- Economics Is Actually About Human Behavior

- The Curse Of Knowledge In Startups

SECTION TWO: Applying Behavioral Economics To Your Startup

- Tweaks

- Adding motivation to our products

- Applying behavioral economics to the core product

Example #1: The Shapa weight loss scale

Example #2: Lemonade – A Business Model Around Trust - Pricing Is Not About Value, It’s About Fairness

Example #1 – The Bank ATM Fee

Example #2: The Netflix Price Debacle - Two Questions To Determine A Strong Business Model

1. “What is causing people to… ?”

2. Test: What’s the friction and what’s the motivation? - When To Rely On Your Users For Feedback (And When Not To)

- Reinforcing The Habits Of Your Users

SECTION THREE: Leadership & Culture

- Mental Models for Effective Founder Leadership & Culture

- Be good at sequencing

- The 3 Elements For Effective Team Leadership

1. Fairness

2. Appreciation

3. Tolerating mistakes - The Secret Benefit of Startups: Reward process versus outcome

SECTION ONE: People Behave Very Differently From What You Expect

People think economics is only decisions about money. But that’s actually not true. Economists get involved with how to set up taxation and education systems and all kinds of things. Economics is actually a perspective on human behavior.

Economics Is Actually About Human Behavior

- The problem is that economists assume rationality. They assume that people have:

- Computational power

- That we’re long-term thinkers

- That there are no emotions involved

- These assumptions mostly give us misleading results. If you have a startup and you take this rational economic perspective, you would, for example, set up pricing as a function of pure cost-benefit analysis.

- Behavioral Economics comes in and says – not so fast! Let’s not assume perfect rationality. Humans are much more complex.

- The basic set up of Behavioral Economics: Put people in different situations and see how they behave. Be empirical about what you see. It turns out that how people behave is very different from what rational theory predicts.

The Curse Of Knowledge In Startups

- A big mistake many startups make is they don’t work enough on their user’s mental model of their product.

- The curse of knowledge is when we Founders know our product so well that we think that it’s clear when it’s not.

- The Microsoft Cortana Example:

- I went to visit Microsoft a couple of years ago. I met the people who were working on Cortana, and they told me that people use Cortana for the weather and jokes and that’s it. I asked them, “Well, what else can Cortana do?” And you can imagine what they said: “Everything.” And I said, “Then you’re not setting up Cortana correctly.” They said, “What do you mean?”

- I basically created the following test. For some people, we said, “Hey, there’s something called Cortana, ask it anything you want.” And so people asked for weather and jokes.

- For other people, we said there’s Cortana for meetings. There’s Cortana for entertainment. There’s Cortana for transportation. There’s Cortana for… and we gave them 10 categories, ask it anything you want. Now people had lots of questions, right? They would say, cancel my appointment. When is my meeting? I mean, they had all kinds of things.

- The thing was that people didn’t have a mental model of what Cortana can do.

- I would say that not helping people create a better mental model of the product and its use is a big mistake.

- Nobody would ever run a biology startup without having a biologist on board, but people have no problem with a startup that is ultimately about consumer behavioral change but doesn’t include anyone on the team who knows about behavioral change. It is surprising.

- The reality is that startups are usually created by people who are amazing at technology but have not mastered an understanding of behavioral change.

- There are a lot of areas where startups benefit a lot from overconfidence. When you come to present to VCs, I mean, there are lots of things where overconfidence is helpful.

- But overconfidence about having intuition about human behavior is not a healthy one. You will be wrong. Getting some help on that is crucial because human behavior is really mysterious — and being wrong results in startup failure.

SECTION TWO: Applying Behavioral Economics To Your Startup

There are 3 main ways in which behavioral economics can help startups: Tweaks, Motivation, and Product. Tweaks are about important little changes. Motivation is about actually understanding the psychology of your user. Product is how you bake all this into your core product or business model.

1. Tweaks

This is basically the practice of seeing something in the process that is slowing people down.

- Setting up the wrong default is a big mistake startups make in this category.

- Defaults really matter. Think about the classic problem of organ donation. It is opt-in. If people have to go to the DMV and sign up for organ donation, very few people sign up. But if you have it as opt-out, people are assumed to be organ donors and they have to sign something to get out of it. So almost everybody becomes an organ donor. The defaults can massively change things.

- Many times when we set up products and signup flows and so on, we don’t truly understand how difficult things are for the consumer and therefore we set up processes in a way that is just too complex, too difficult. We can look at the signup flow and you say, “Hey, you’re asking people a question here that you don’t really need to ask. It’s too difficult. It’s too complex. People are dropping off.” There are a lot of tweaks around that to optimize.

- Now it’s not just about defaults. It’s of course even more complex than that.

2. Adding motivation to our products

Human behavior is magical and fantastic and complex. We’re capable of all kinds of things like climbing mountains and writing books and doing startups, but our motives for doing all of these things are much more complex.

- If you write down an equation of what gets you up in the morning and gets you excited about what you’re doing, it will not be an equation that is driven purely by how much money you are making. We have lots of other motivations. And whatever works for us works for lots of other people, and therefore we need to put motivation into our products.

- Example: The Missed Doctor’s Appointment. We worked with this HMO that had a problem of people not showing up for medical appointments. So they started sending these text messages to remind people, saying: “You have an appointment to meet a specialist. Please show up on time and if you’re not going to show up, please follow this link and let us know you’re not going to make it.”

- They thought that people were not showing up because they forgot. But even with multiple reminders, more than 20% of the people did not show up on time. It’s very hard to run a healthcare system when 20% of people don’t show up.

- The HMO asked us for help and they limited us very much. They said the only thing you can do is change a text message. We could have designed systems to give people points and reputation and money — the world of motivation is very broad — but they limited us only to the text message language.

- So we tried different things.

- Some people we reminded that their family wants them to be healthy.

- Some people we reminded the name of their doctor. Remember Dr. X is looking forward to seeing you on this day and this time.

- For some people, we reminded them about the nurse. Remember nurse Y is going to see you.

- For some people, we told them how much it would cost the HMO if they don’t show up.

- We reminded people about their own commitment to health.

- We did all kinds of things and one other thing we told them was that some other patient could use their appointment if they don’t show.

- The results: The first thing that happened is that all of our methods worked better than the control condition. Add the source of motivation and everything worked.

- The thing that worked the best was to say another patient could use your appointment. We cut the no-show rates by more than half. A huge financial impact on such an organization.

- We also wondered: “What if we could tailor the specific message for each person? How much better would it get?” The results we got are basically the famous 80-20. More than 80% of the value from picking one message that was the best for everybody, and then just a little additional value by tailoring it specifically for the individual.

- We conclude from that: How much are people similar? Mostly we’re all the same. The same thing works on everybody and there are some tweaks on the edges.

3. Applying behavioral economics to the core product

Founders need to ask earlier in their startups: What is the role of behavioral economics in the core product or the business model?

Example #1: The Shapa weight loss scale

- If somebody gives you two square feet of their prime real estate, take it. We started with a bathroom scale and then we studied the bathroom scale, and I know it sounds a little ridiculous, but it turns out there is a lot to study in the bathroom scale.

- There are lots of ways to get people to lose weight, but if you start thinking about this from a behavioral economics perspective, you say the following: Okay, the struggle for health is a daily struggle. You can’t be healthy five days of the week and not healthy two days of the week with food, right? You need consistency.

- In psychology, there are basically models of recall and models of recognition.

- Recall: is something that you think about yourself. Like you walk around the house and you say, “Oh, let me think about my long-term savings or my diet or my health.” It happens occasionally, but not that much.

- Recognition: happens when you see something and that reminds you of something. When we have things in the environment, they remind us of things.

- The obesity epidemic in general, it’s a 200 calorie a day game. If you can cut 200 calories a day systematically, basically people lose a pound every two weeks. That’s incredible.

- It’s just about how to do it on a consistent basis. That’s why people don’t. Being consistent, naturally, is hard.

At Shapa, here are three things we learned.

- It’s about timing. First thing, it turns out it’s really good to stand on the bathroom scale every morning. Not so good to stand on it at night. Why? Yes, we weigh more at night, but that’s not the reason. If you stand on it in the morning, you remind yourself first thing that you want to be healthy and then you eat a little bit less throughout the day. If you stand on the scale at night, you just go to bed. By the morning, you forgot the whole thing. That reminder doesn’t work for a long time but if you have it just before breakfast, it’s very effective.

- Leverage loss aversion. Loss aversion is the idea that we hate losing money more than we enjoy gaining money. With weight, of course, it’s the opposite. We hate gaining, we like losing. But they’re not symmetric. Imagine somebody who goes up and down in their weight. We all fluctuate, right? Somebody fluctuates up and down, up and down. The ups are really miserable. The downs are slightly happy, but on average, it’s not good news every day on the scale. High misery, slight happiness, over again. Basically, we don’t feel good about it.

- People are impatient. The last thing is it turns out people expect their bodies to change very quickly. People say I’ve been on a diet since yesterday morning: Where are the results?!

- Here’s how we applied behavioral economics. We said, “Let’s build a scale with no display. Let’s give people the feedback on an app, but in trends of the last three weeks.”

- Let’s not focus on the numbers. The numbers are confusing and de-motivating. Let’s give people the trend.

- Then we had to determine if we showed five trends or four trends? What do you think, is it better to have a five-point scale or a four-point scale? If you show 5 trends you can have a middle. Is it good to have the middle?

- Imagine a year, 52 weeks, and imagine somebody is losing weight 12 weeks and nothing happens for 40 weeks. Is that a good year or a bad year?

- This is where it’s so important to understand the psychology. Because if people encode nothing happened as bad news, a year when you lost weight 12 weeks and nothing happened 40 times, you would feel like a failure. But it’s an amazing year! In this situation, we need to give people credit for when nothing bad happens. So we created a five-point scale and we celebrated the middle.

- By the way, the colors we used matter too because we wanted to make the neutral sound positive. We gave the neutral a green color. We made the decrease in weight in blue colors, and we made the increase in gray colors. We separate the green and we give you extra points for it.

Now, how did we test our Shapa scale?

- We went to call centers. We wanted people who were relatively low income and relatively obese because those are some of the toughest populations to change. Right? If you get people in your test who are already highly motivated, that’s not as interesting.

- The people who got the control scale, the regular scale, a digital scale that tells your weight every day — they gained 0.3% of their body weight every month. Gain, gain, gain, gain for the six months of the study.

- The people who got our scale lost 0.6% of their body weight every month. Lost, lost, lost, lost.

- 79% of the people stood up on the scale five times or more per week. It was not frightening anymore. It was not aversive and they did it.

- They understood better the relationship between cause and effect.

- Information works in 3 ways:

-

- Adds motivation.

- Helps people understand the relationship between cause and effect

- Adds accuracy.

- I want to create interfaces that motivate first, then help people understand cause and effect, and then are accurate.

- It’s all about the perspective of thinking about all the little details.

- Statistical software is great with dealing with variance, but people are not.

- The moment you take seriously human behavior, motivation, understanding, and what do we do with variants… then you can start designing your product from the beginning taking these principles into account.

- It’s really critical to think about them early on rather than trying to patch them onto your product later.

Example #2: Lemonade – A Business Model Around Trust

I met Shai and Daniel before they started Lemonade. They came to talk to me about insurance and their question was, what are the biggest barriers to insurance? This was great because they didn’t say, “Okay, here’s the product, help us tweak it.” They started directly with what’s the barrier for insurance? [Related: What’s the single miracle to overcome?]

- I told them: Trust. I said, and here’s the situation with insurance. You as a consumer pay the insurance, pay the insurance, pay the insurance. At some point, something bad happens and you want them to pay you back, but they have your money and they write the rules. The question is, do you trust them? If you don’t trust them, are you going to be dishonest? Not trusting the insurance company creates a vicious cycle. What happens is that people lie to the insurance company. The insurance company spends a lot of money to adjudicate claims because they don’t trust people, and the whole system is losing lots of money. Adjudicating claims is what’s called a deadweight loss. Everybody loses money.

- We needed to eliminate conflicts of interest. When you have people with conflicts of interest, they often don’t see things correctly.

- We decided to change it from a two-player game to a three-player game. Let’s have the consumer, Lemonade, and the charity. When people sign up, they pick their favorite charity and they pay Lemonade, and Lemonade always takes a fixed amount as our profits, but we keep the money in the pool. Let’s say you joined Lemonade and you signed up and you chose the World Wildlife Fund as your favorite charity. We take all the people that sign up under the World Wildlife Fund in your one pool and you pay money into Lemonade. We take the fixed amount. We pay back claims, and if there’s money left over in the pool and we design it so that there’s a very high likelihood there will be money left over in the pool, then that money goes to the World Wildlife Fund.

- Lemonade baked trust into the business model from the beginning. It didn’t have a 200-year reputation, and trust is the main barrier, so we knew we had to make a business model around trust.

Pricing Is Not About Value, It’s About Fairness

Pricing is not about value, it’s about fairness. But many startups get this wrong. Let’s look at pricing examples of this.

Example #1 – The Bank ATM Fee

- I met with a bank that said they were going to change the ATM fees. They wanted to stop charging a $2.50 service fee to take money out.

- Them: Oh, people will love us because we’re making it free.

- Me: People will hate you if you do it for free.

- Them: People would be grateful.

- Me: People would say: You bastards, why did you charge me all these years.

- Me: What you should do instead is tell people: “Look, it really costs us $2.50 to provide you with this service but if you don’t have the money to pay for it, pay us less. It’s up to you.” I basically used the name your own price approach. This way, you don’t have to go to zero. The worst that can happen is that people will pay you nothing — but critically, you’re not communicating to people that this costs you nothing.

- They did it their own way, and it backfired exactly as I predicted. In follow-up tests, it turned out that my approach would have been much better.

- The point is: Pricing is not about the value, it’s about fairness. If you just reduce the price to free, you’re basically telling people we could have charged you nothing all along, we just didn’t. And that would create tremendous anger because of fairness. Not because the service is not worth $2.50, but because of fairness.

- This is an example that shows if you take the rational perspective, it just leads you to the wrong conclusions. If you understand the complexity of human beings, even for small decisions, it matters a great deal.

Example #2: The Netflix Price Debacle

- Remember what happened to Netflix when they split their services? Netflix started as a company that used to send DVDs to people at home. Then they had the streaming service on the side. But as the internet became faster and faster, the streaming service became more and more popular and at some point, they said, “Okay, let’s split it.”

- I don’t remember exactly the numbers, but let’s say it was $14 a month. Instead of $14 a month for both streaming and DVDs, we’ll make it $8 a month for DVDs and $8 a month for streaming. [This costs you $16 now if you want both, vs. $14].

- Wall Street analysts were ecstatic about this. They said, “Oh, revenues will go up. New people would sign up. A lot of good things will happen.”

- They announced it and I think a million people quit Netflix that day.

- What happened wasn’t that the deal was not better. It was better because most people did not need both the DVDs and the streaming. They could use only one of them and pay less. For most people, they were getting whatever they were getting before for less money.

- But what happened was that people felt it was unfair. “Why are they increasing the prices for me from $14 to $16?”

- By the way, yes you can absolutely increase prices. You just need to do it in a way that people feel is fair. When you look like you are price gouging, people get so angry with the company, they are willing to quit a good service just as an act of revenge.

Two Questions To Determine A Strong Business Model

1. “What is causing people to… ?”

- What are you assuming about your users? What is motivating them? What is causing them to want something versus something else?

- You can ask the question of what is causing people to eat large portions, or what is causing people to not keep to a diet? What is causing people not to repay the debt?

- I would not start with what the competitors are doing. I would basically ask what is my model of humanity as it interacts with my product?

- Be explicit about those assumptions and write them down, because a lot of times when you write these assumptions, you realize maybe you’re not as sure about the assumption as before. You basically want to write out your assumption.

- For example, if you’re talking about paying debt, you could say, “Oh, I’m assuming that people want to pay their debt back. How much? What kind of debt?” The moment you get into it, you can start seeing what you’re assuming.

2. Test: What’s the friction and what’s the motivation?

- I think this part is where the rubber meets the road.

- Basically, go very slowly through the experience with your product, and at each point, ask yourself, what’s the friction and what’s the motivation. What is holding people back and what would give them extra motivation?

- There’s this belief in “get out early and iterate.” My experience is that startups do get out early, but they don’t iterate until it’s too late. And often the experiments are not that good, so it’s harder to learn.

- You would think, at least I thought the electronic world would give us amazing platforms for testing. The reality is the testing is tough. It’s hard to know how to create the test correctly. It’s hard to run tests. Sometimes it requires extra work, and a lot of startups I find don’t do enough testing.

- Founders basically are so driven to build quickly. The slowness that is required by testing something it’s just very unappealing. So I think we don’t test enough.

- It’s like a microscope. You want to go over it incredibly slowly and at each point, you ask yourself two questions, what is holding people back and what would motivate them? What would get me to sign up and what’s causing me not to sign up?

When To Rely On Your Users For Feedback (And When Not To)

It’s not that people lie. They actually believe in it.

- In general, there are 1) things that people can report and 2) things that people can’t.

- I’m quite comfortable asking people to report what they have done. I can ask you, for example, did you check social media yesterday, right? Would you be aware of exactly how much time? Probably not, but can you tell me if you checked it yesterday or last night or before you go to sleep? The answer is yes. People can report quite well on what they have done, with some limitations.

- But I would be very hesitant to ask people for their intuitions about it.

- Here’s just an example. It turns out that retirement savings, the 401(k) in the US, is basically driven by default. If when you come to a new job, they default you into 401(k). You save. If they don’t, you don’t. Big differences, some people do, but huge differences, but if you go to people and you ask them why didn’t you save and why you didn’t save? Nobody says it’s the default, right? People have stories.

- Basically, lots of times we act as a function of the environment that we’re in, but when we tell ourselves the story, the story is not about the environment. The story is about something intrinsic in us, and we make the story so quickly that we start believing in it, right?

- It’s not that people lie. They actually believe in it.

- Founders who trust the intuitions of their users are at increased risk to two of the 6 failure patterns identified by Harvard Business School Prof. Tom Eisenmann in a recent NFX podcast: “False Positive” and “False Start.”

Reinforcing The Habits Of Your Users

Another mistake from startups is not thinking clearly about what pattern of use we want to create, and how do we reinforce habits for our users.

- Startups have measures like daily active, weekly active — but the real question is are people using the product at the frequency and timing that we want them? And what is the model for repeated use that we have and how do we create that?

- Is this a product that would be very useful to try and get people into a habit of checking every Monday morning or Sunday or Friday? What is the right cadence and what do we create in the environment to become a trigger for that?

- People have busy, complex lives and therefore we need to realize that the time that they’re giving us is very, very limited. People have very, very limited attention and time.

- When we design products, we often think that people care about the things we care about. We think: Here I have this new product. People would probably read the manual. I want to lose weight and people after all want to control their diabetes but the reality is that people have very little time and very little attention and if we design with that in mind, I think we’ll make much more progress.

SECTION THREE: Leadership & Culture

Mental Models for Effective Founder Leadership & Culture

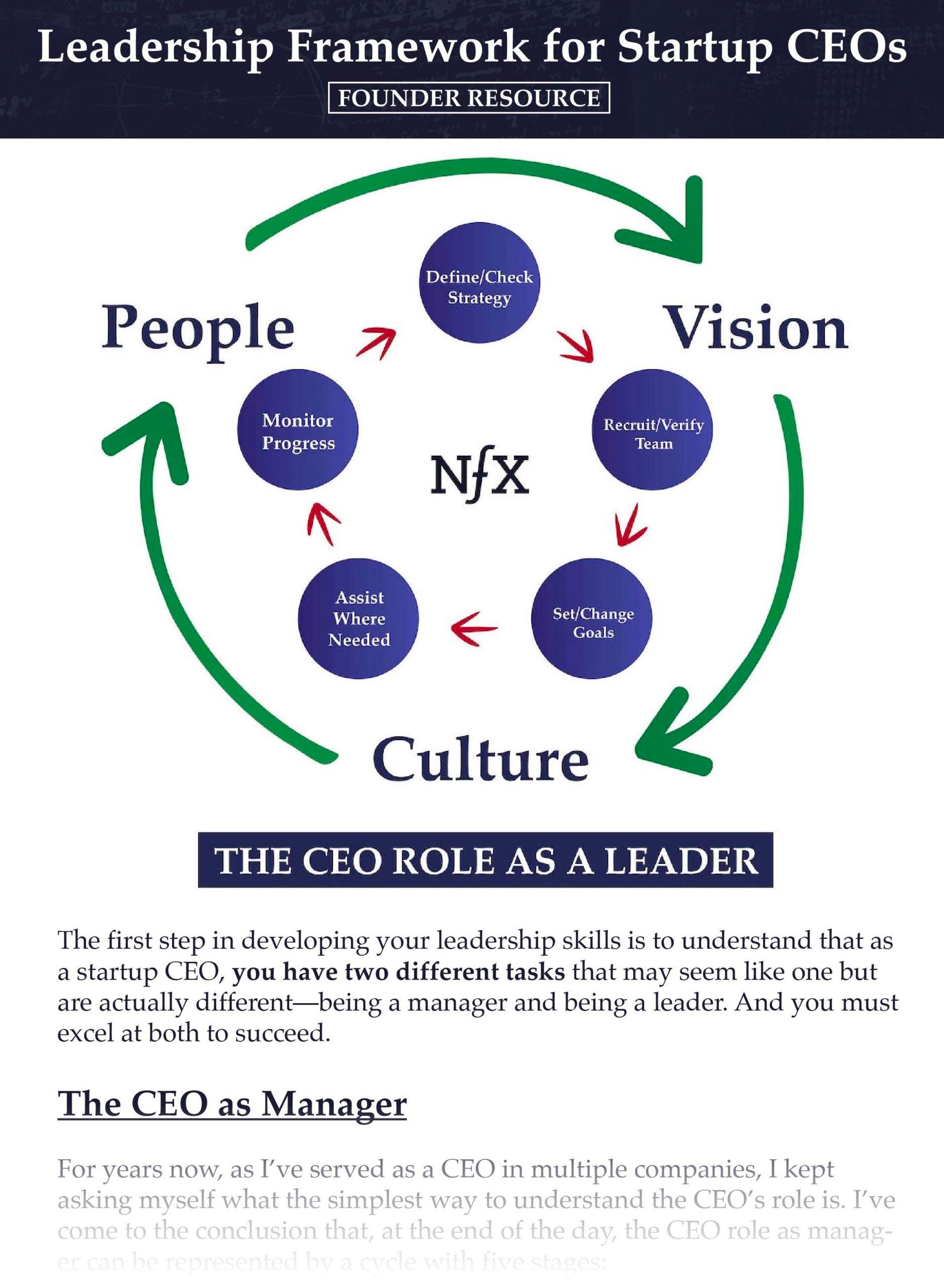

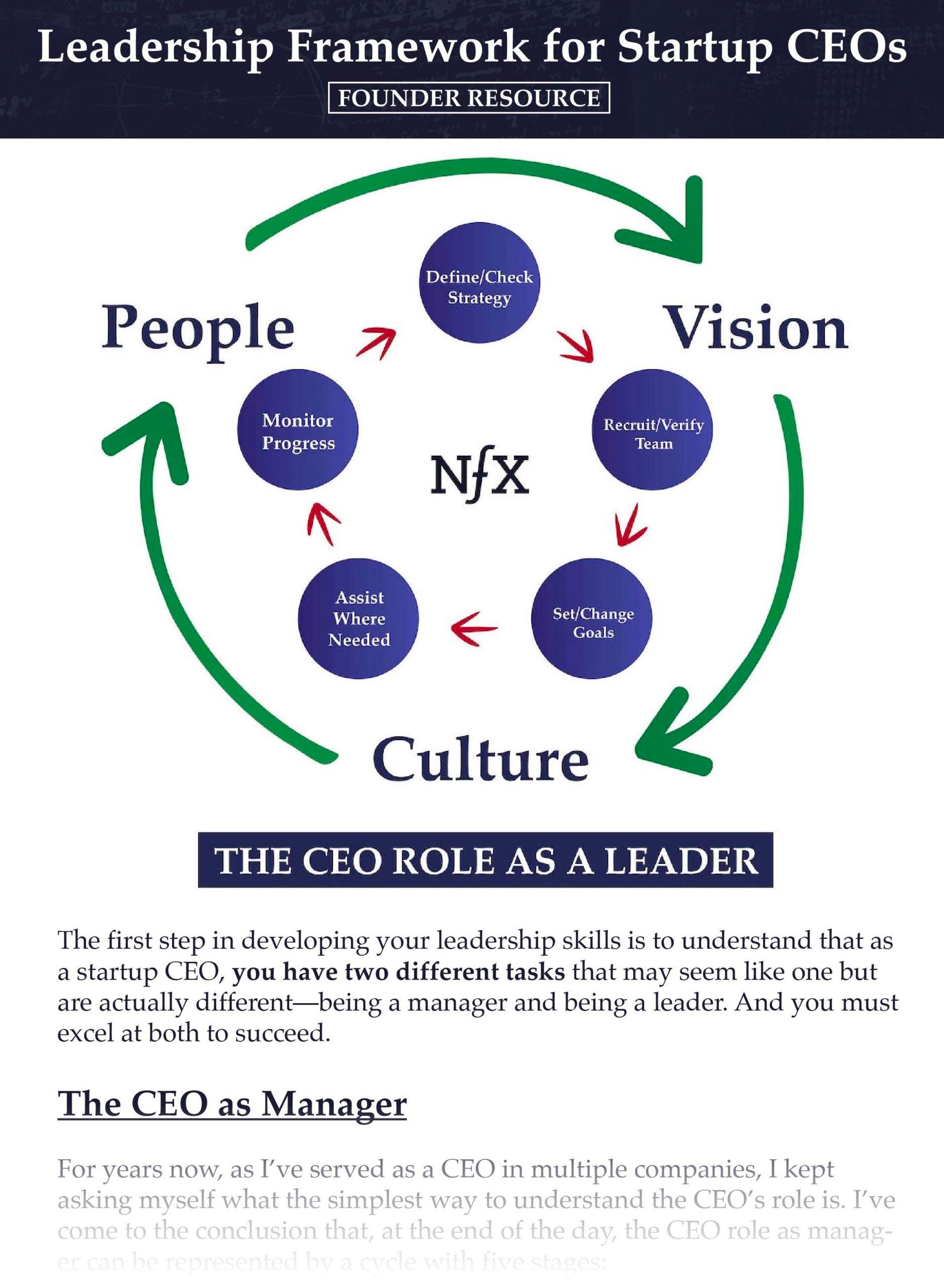

What are behavioral economics elements that can help Founders become the most effective startup leaders? What can they learn from behavioral economics to become more successful at that job? There’s a 2 part framework: 1. How you lead the product and 2. How you lead the people.

1. Be good at sequencing

- Scientists and engineers and logical people often want to test everything possible. But you can’t test everything. I think good leaders are able to separate core assumptions of the product and figure out what to test and what to make assumptions about and what not to assume, and they can sequence it the right way.

- They can say what are the right building blocks, and what to test when? That would be number one and two for the product.

- “Here the central assumptions we’re making, I’m going to test this assumption first and then this, and then we’ll move to smaller things that are less important.”

- You can say, for example, in Lemonade’s case, it was first let’s test trust. Let’s test the charity model. Later on, we can test things like pricing and whether we could get people to like Lemonade more, answer more questions, and so on.

2. The 3 Elements For Effective Team Leadership

Appreciation, fairness, and tolerance to mistakes are the three elements that get startup leaders to be the most effective in leading their companies.

- I’ve been doing this study for the last four years now, trying to understand how companies treat their employees, how the employees feel about the company, and what it means for the profitability of the company in the stock market. I’m doing it on public companies in the US but learnings apply to startups.

- I studied 80 different components, but when I go to HR managers and I say, what do you think matters and doesn’t matter — they’re wrong. Their intuition about what matters is just not that good, and this is why people dig deep into their intuition. They’re not necessarily going to get it right because some of the things that motivate us are very different and it’s also very hard to intuit that when you’re not in that situation. We have something we call the hot-cold empathy gap. The hot-cold empathy gap is the idea that when you’re in a cold rational state, you don’t really understand how you would be when you’re in a hot state. When you think about things outside of that situation, it’s really hard to intuit what it would mean to be in that situation.

1. Fairness

- Do you think that salary matters for profitability? Do companies that pay employees better, the employees feel that they are getting paid better, are those companies more profitable? Yes or no? The answer is No.

- Perception of fairness in salary matters a great deal, but absolute salary doesn’t matter.

- Quality of coffee doesn’t matter. Quality of furniture doesn’t matter. Employee benefits don’t matter.

2. Appreciation

- Appreciation matters dramatically. The big lesson we have from motivation is that appreciation is incredibly important.

3. Tolerating mistakes

- What really really matters is people feel that they can make mistakes. Honest mistakes are valued.

- The thing about tolerating mistakes is about agency, right? It’s about giving people the ability to move forward in the way that they think is right and allowing them to make mistakes as well. You want people to move forward and when they’re trying something new and interesting, whether it’s working or not working, you want to reward them for it.

- All companies basically when you talk to them, they want people to take more risk, and try to innovate. Well, they think they do or at least they say they do. They don’t necessarily behave as if they do. So now the question is, how do you also get people to behave this way and not just to say it.

- It’s not about accepting stupid mistakes. It’s about rewarding the process versus outcome. I try to encourage my team to be wrong at least 50% of the time.

- If you’re right too often, it means you haven’t tried things that are sufficiently interesting. Because it’s very easy to do studies that always work as you expected if you’re assuming very boring things.

The Secret Benefit of Startups: Reward process versus outcome

- Imagine you have a kid and one day your kid studied really well for the exam, but the exam asked about some side issues and your kid did not get a good grade.

- And then another kid didn’t study at all but went to the exam and the exam asked him the one thing he knew and he aced it.

- Do you want to punish the first kid and reward the second? The answer is no because in the long-term what the first kid did is going to be the right thing and what the second kid did is not. What you want to do in reality is reward behavior, not outcome.

- We often do the reverse, we reward outcome and not behavior.

- I think this is a real benefit of startups. As companies get big and bureaucratic, they set up procedures. Procedures are inherently trying to get things up that are measured by outcome. By contrast, startups are much more flexible, and I think one of the benefits is to use the size of the startup to truly understand what people are doing, not what the outcome is, and to correctly reward the right people with fairness, appreciation, and tolerance of innovative mistakes.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.