Silicon Valley loves patterns and playbooks for executing on market disruptions. Take a great startup, break down its wins into a series of actions and reactions, and then follow that blueprint. Simple, right?

What rarely comes to light is that the great Founders do not study rules so they can follow them. They master the rules so they can break them. Underlying their vision are mental models that get at the key question: Which patterns do you violate, and why?

As a Founder, the clarity of your thinking behind that question is defining because, as my friend Keith Rabois puts it, “If you’re trying to reinvent everything, that probably means you’re not really successfully reimagining anything.”

Your highest leverage is studying the rules as a starting point, but spending much more time on the mental models — the psychology — behind rule deviation.

This essay and podcast is an examination of the rule deviation behind some of technology’s greatest startup feats — PayPal, Square, Yelp, and even touching on Apple, Tesla and SpaceX. Keith has been instrumental as an early team member in many of these companies. He’s had a storied career in Silicon Valley, and he now is a partner at Founders Fund.

Whether you agree or disagree with Keith’s conclusions is not the point. The point is — as always — creating something of true significance starts with seeing what others do not.

Let’s jump in.

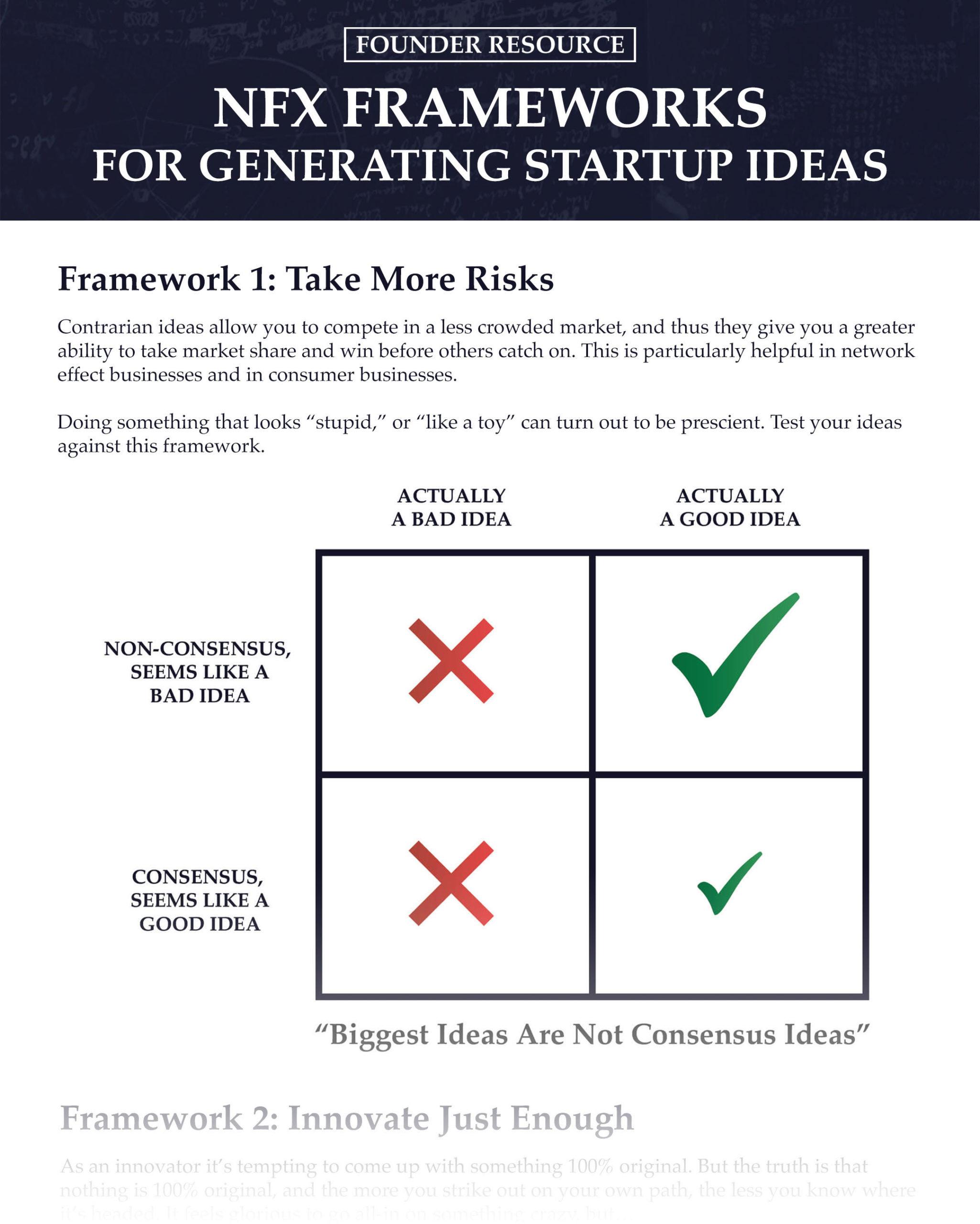

1 ) Being a contrarian is easy. The challenge is being a contrarian and being right.

- The basic principle of a contrarian is the ability to think for yourself, on any topic, and being able to derive a set of views independent of what other people around you think.

- That’s very difficult to do because everybody is mainly influenced by the 5 people you spend the most time with.

- For Founders, it’s a whole lot easier to build a business when you see the world differently at first. That gives you time to develop it, build traction and momentum, and accumulate advantage… before the rest of the world realizes that you’re on the right track.

- Peter Thiel wrote about this in Zero to One, where he talks about secrets. What secrets does the Founder have or team have, that are insights about the world that everybody else thinks are wrong, but prove to be accurate?

- The challenge of being a contrarian is not in being contrarian. The real challenge is the Venn diagram overlap of being right and different.

- Reid Hoffman has a great quote about this: ”It’s actually pretty easy to be a contrarian. It’s hard to be contrarian and right.” Jeff Bezos has said the same thing.

- Personally speaking, I am an anti-FOMO person. I prefer JOMO — I run my life around the joy of missing out. The more things I’ve missed, the happier I am.

- I grew up in an anti-war household that loved George McGovern. Then I went to Stanford, which was incredibly leftist when I was there — borderline Socialist or Communist — and I survived that. Then I went to law school, which is full of left-wing professors. Now I am a conversative in Silicon Valley. So maybe to some extent, I might go crazy if I was sitting around with fellow conservatives all day!

2. Only after you’ve mastered the rules do you get to violate them.

- The art in most fields is understanding the rule precisely, and then knowing when to deviate. There’s truth to that in Silicon Valley too, that deviating from rules doesn’t make much sense, per se. It’s knowing why you’re deviating from the rule.

- I remember the first time I learned this. I was a kind of annoying high school kid, and I remember sitting in English class and reading some of these great works of literature and noticing that some of the best authors of all time would occasionally violate grammar rules. And I’d ask my teacher: “Why does my paper get marked up when I do this, but so-and-so famous author gets away with it?” And the correct response by my English teacher was: “Well, when you master all the rules you get to violate them.”

- If you follow the rule book, you’re not going to create an iconic company from scratch. There is no rule book that tells you how to build the next SpaceX or Tesla by definition. And so you need to know what rules you’re going to change.

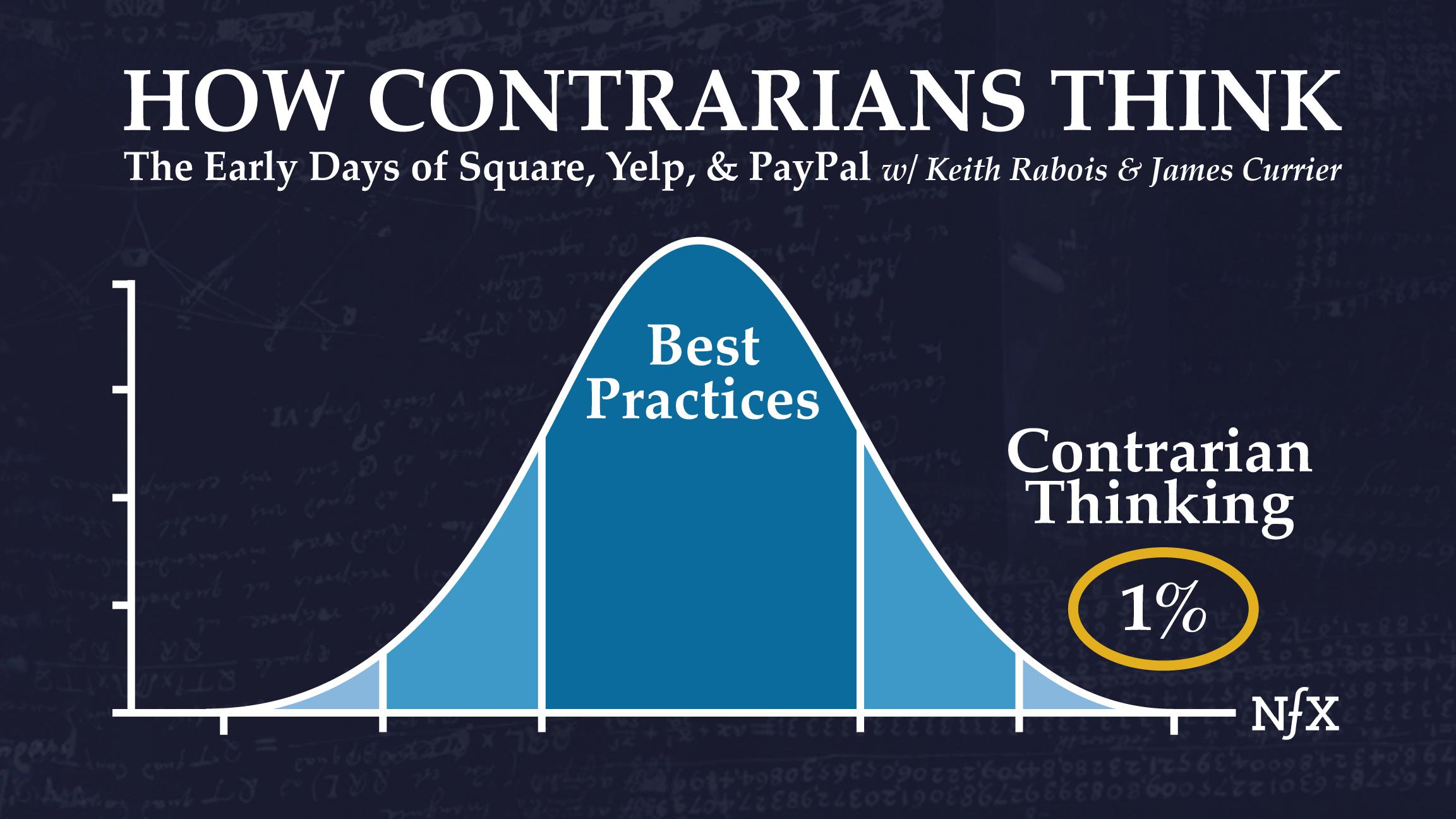

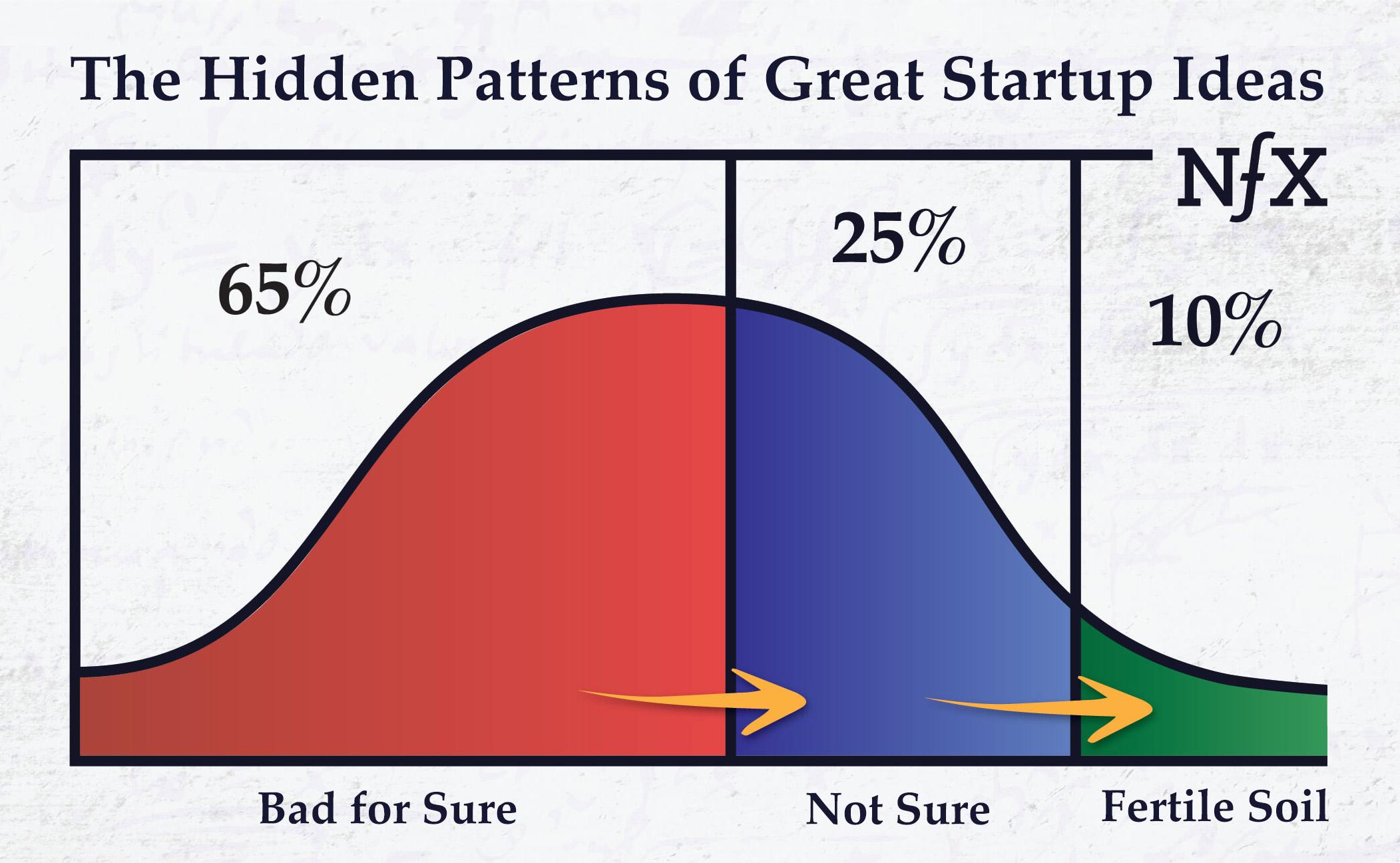

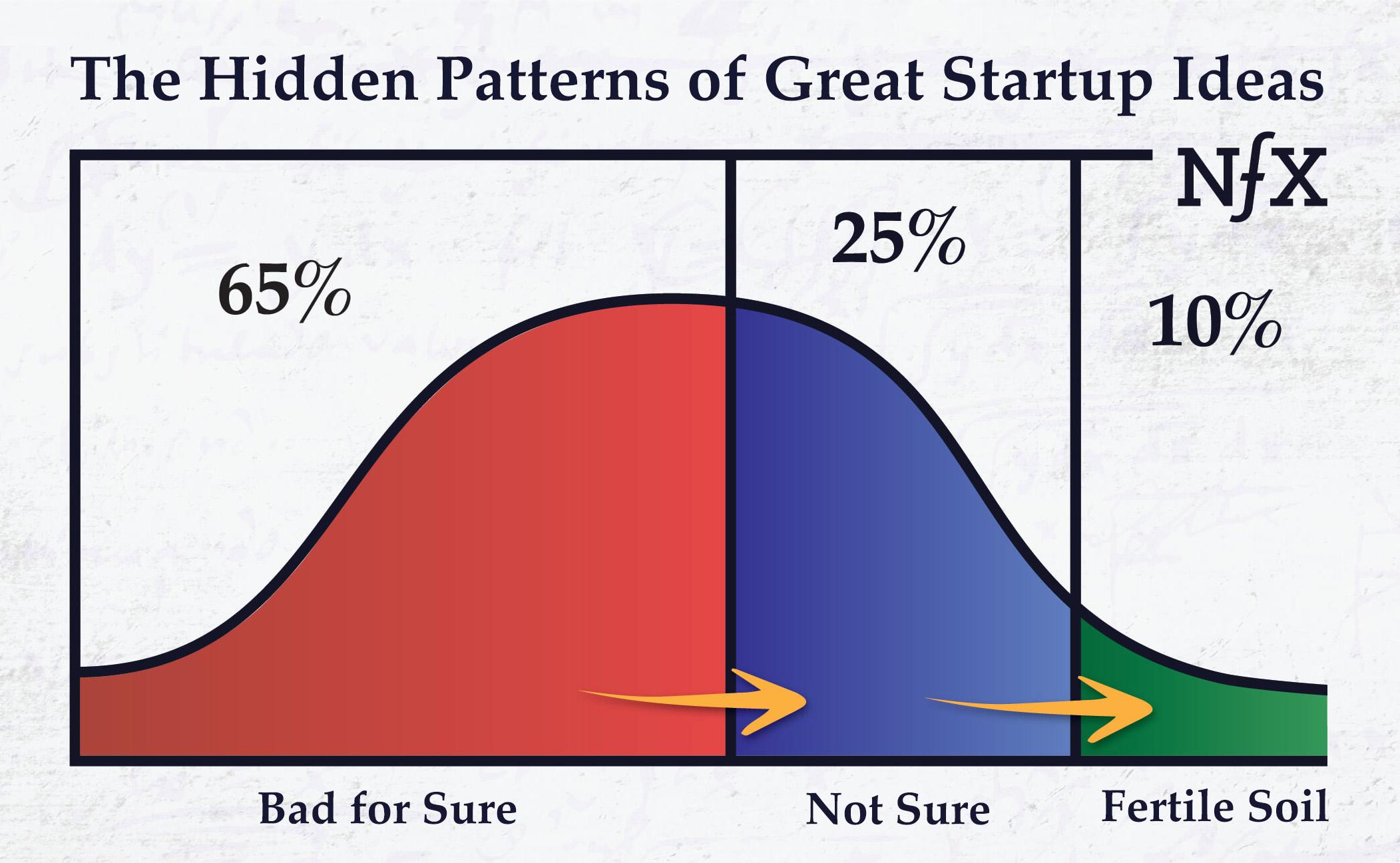

- That’s why I don’t like the phrase “best practices.” Best practices just lead you to the replication of something else. You can borrow best practices, but you need to know where you’re intentionally not following “best practices” or you’ll just be in the middle of the Bell Curve, which is not the goal. You need to be at the extreme one percent. So you want to consciously violate some of the rules, but have a very intentional strategy for doing it.

3. Case Study: How Apple breaks the rules

- It’s a closed platform. For 20 years, most people have argued you don’t build a closed platform.

- It’s a secretive company; they don’t let their different teams talk to each other inside the company.

- They don’t actually use metrics for the most part to measure themselves. That’s all very unconventional. All three of those things would violate most Silicon Valley norms, but they’re indispensable to Apple’s success. There’s a reason why they are the most valuable technology company today.

4. At PayPal, we didn’t think we were misfits. We just knew something the world didn’t appreciate yet.

- There have definitely been times at many companies I’ve been involved in when the world thought we were crazy.

- For example, Red Herring magazine, which at the time was the centerpiece of Silicon Valley technology consensus opinion, ran this cover story on PayPal called “Earth to PayPal.” Peter (Thiel) never forgot this. When we celebrated our IPO, he held up the cover. When we celebrated our acquisition by eBay, he gave another speech holding up the cover. So, we definitely were considered to be weird, odd misfits at the time.

- I don’t think on the inside we thought we were misfits. Our companies were making, for the most part, quite wise decisions. Whether the world appreciated it or not… that wasn’t the key criteria for us.

5. How “The PayPal Mafia” broke the rules — and won.

- The number one thing is to really credit Peter and Max for their recruiting. They had a philosophy of finding the right people and ultimately sourced a huge fraction of the PayPal network through their personal networks. Peter, through his connections at Stanford, and Max mostly hired engineers out of his high school experience in Chicago or from the University of Illinois. They identified people with high potential at scale and mixed everybody together.

- Once we were in the building, there was a set of management philosophies that were very different at the time, which may have enabled us to be successful with this company and then also subsequently. For example, we didn’t really believe in general managers. Peter was adamant that we were not going to hire people whose skill in life was managing. We were going to promote the best person in each discipline to lead that discipline. So for example, the best engineer would become VP of Engineering, the best designer would head the Design team, the best product person would lead the Product team, the best finance person would be CFO, and that led to a building of craft and gave a meritocratic feel. Everybody knew that their boss was actually pretty damn good at what he or she did. So I think that was pretty fundamental.

- PayPal was a hard business. It was very challenging. There were a lot of obstacles, a lot of people and enemies that didn’t really like us, ranging from Visa, MasterCard, to federal and state governments at different times, eBay, et cetera. So it was sort of a trial by fire situation. You definitely bond with people in that kind of environment, and you get to see who’s really good under pressure and stress and who actually doesn’t thrive under those circumstances. So, after PayPal, when people subsequently went to start their own companies, I think a lot of us already knew how each person would do as a Founder. Peter and I talk about it all the time… being a Founder is like chewing glass. It’s not particularly fun, it’s very painful, it requires a lot of self-actualization and initiative. And I think our time at PayPal gave us pretty good insight into who was likely to thrive in that environment. And that’s why I think some of my colleagues’ companies did really well.

- When we all exited PayPal and were investing in or starting new things in 2003, 2004, 2005, most people didn’t think that there was another wave of consumer innovation that was likely to be successful. We happened to believe there would be, which is why we started all these companies, funded each other’s companies, etc. History will record that as being right, but it wasn’t obvious at the time.

6. Counterintuitive KPIs in the early days of Yelp, PayPal, and Square.

- It was probably the second board meeting we had since I joined the board of Yelp. I remember Jeremy Stoppelman was finishing his presentation and he basically gave us this vision that Yelp was really building this viral social product, which not everybody appreciated at the time. I looked across the table and said, “Okay, well, if you’re building a social product, what’s the key metric that’ll tell you whether you’re right or wrong?” And he looked up and down the table and said, “It’s the number of unique, one-on-one personal messages from one member to another.” And personally, at the time, I thought the answer was ridiculous. But very quickly thereafter, certainly within three to six months, I realized he was actually right that that was the key predictor for whether we were building a true community. It was extremely counterintuitive at the time.

- I’ve given you the PayPal example too. Nobody really believed that eBay was a target market for PayPal. But then David Sacks noticed that there were 54 sellers on eBay who had hand-typed into their listings: “Please pay me through PayPal.” It was a very small number obviously, and the first reaction of the PayPal executive team was, “Oh my God. Why are these people using PayPal? We should get rid of it because that’s not what we’re supposed to be doing.” But then David came into the office the next day and said the opposite: “A-ha! I think I found our market.” So we created a PayPal logo that they could insert, as opposed to type, and then we created an automated way to insert the logo because these sellers had lots of listings. It basically became both the market for the company to focus on, as well as the guiding light for the product strategy for two years.

- Back when I joined Square, we were just launching and we’d shipped about 10,000 or 20,000 Squares into the world, and we started to grow. Here’s what happened:

- We weren’t doing any marketing; we didn’t have money to do marketing. But I remember Jack pointing to his computer the second week after we shipped the Squares, and noticing that day by day, we were adding more users per day, growing a little bit each day. And he asked me, “Why is this happening?” And I paused because under the standard set of rules it really shouldn’t have been happening. We weren’t doing anything to create this growth.

- So I thought about it for a few minutes and I formulated a hypothesis. And it was really only a hypothesis given the constraints. I thought, “A-ha! Maybe this is a function of people seeing Squares in the real world, seeing the actual device, and some fraction of them that see it, sign up.”

- So once you have a hypothesis, then the next question is, “Well, how do you validate that? How do you test it?” If true, there should be a ratio for every new Square we shipped, and every new customer, and every transaction in the rate of growth. Turns out there was a perfect relationship, it’s exactly 1%. So for 1% of all transactions on let’s say day zero, we have 1% of signups the next day, new signups, and they just were perfectly consistent. This is amazing. We now have an actual viral loop in the real world. We had this observability. We’ve been in the real world that’s causing growth, but it was not at all obvious.

- We decided this word of mouth was partly from the aesthetic appeal of the device, the consistency of the design of the device, with the name of the device, so people can remember. You see the square, it’s called Square, and that’s easy to remember when you want to go sign up. It worked for the early days.

7. The team you build is the company you build (especially remotely).

- I learned this from Vinod Khosla when he was on the board at Square. He said, “The team you build is the company you build.” At first, honestly, I found it a little surprising, because typically people in Silicon Valley think about technology and technical advantage and IP, and then they think about distribution advantages, and distribution strategies and network effects. They often forget the people and the way he expressed it, it was just so simple. It was one of those things that every minute you think about, it gets more and more powerful and insightful. He mentioned this to me maybe 8 or 9 years ago, but I still think about it every day. The team you build really is the company and with the right people you might have a phenomenal company, but a lot of people have an unmitigated disaster and most companies are somewhere in between.

- Regarding teams doing remote working accelerated by COVID019: The benefit of being co-located is mostly extemporaneous conversations; dialogues that wouldn’t have happened by scheduled meeting, by fiat, by calendar or by remote. It’s the step-function of innovation that I do worry about remotely. I think about how many really good ideas at PayPal came from spontaneous meals together or spontaneous late nights, like over a drink or pizza. Some of those ideas are really 10X ideas. But ideas happen in random time intervals.

- A lot of people are trying remote for the first time right now. The good thing is their existing relationships at all these companies that are suddenly switched to remote because of COVID. I do wonder about how high fidelity the debates and dialogues would be if there were no preexisting relationships from the real world before these companies had to go remote.

- It goes back to knowing the rules. I think there are some advantages to remote working if you know which rules you actually can’t break.

8. Ridiculous ambition + knowing which rules to violate = exceptional Founders

- Founders need to think about what they are doing differently and why? What are their secrets? Why are they likely to have unreasonable success?

- I mean, if you think about it, it’s heroic, almost ridiculously so, to have someone raise their hand and say “I’m going to change the world.” “I’m going to change the entire financial services world.” “I’m going to change the entire real estate world.” “I’m going to change this entire whatever.” That’s kind of ridiculous. But you need people who can take on ridiculous ambition.

- That’s when you can have a dialogue about, “Well, what rule do you violate? Why?” And that allows you to understand how the person’s brain works and the calculations they’re making.

- The bad version of that conversation is when they don’t even realize they’re violating the rules, or they don’t understand the reasons why they’re deviating. That’s usually a disastrous recipe for a mess because you don’t want to violate all the rules. You want to select the least. If you’re trying to reinvent everything, that probably means you’re not really successfully reimagining anything.

- Look for people who are ambitious, definitely. There’s ambition and then there’s ambition. I like to find the outrageously ambitious people. Borderline a little crazy. I’ve certainly worked with and worked for a lot of people that fit that DNA, so it doesn’t bother me. I expect that it’s part of what makes the person super impressive. When they see the world differently, I expect they will occasionally have very strange reactions to the world.

- The people who really want to walk through walls, who you know will walk through that wall one way or the other — that’s basically the most important thing in a Founder.

- Then they need the IQ and horsepower to understand why and how to walk through that wall.

- When you meet a Founder, it’s very hard to project beyond what this person is capable of today — instead you want to project what is this person going to be like in 10 years? And that’s really a growth question, so you’re looking for a sustained rate of growth.

- What makes the exceptional Founder, the real outlier, can be one of two things. They are either outrageously good at one dimension — extremely world-class. Like, “I have never seen someone like this in X-dimension.” Or they have a compounding rate of learning that’s absurd. And you get to go along for the ride and for five or ten years and just watch them grow.

You can listen to the podcast conversation here.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.

Try ChatNFX