For Founders, market needs are often a lagging indicator of technological progress. In many cases, like the iPhone, we didn’t even know that we needed a thing, until the thing made us want it.

Visionary Founders, instead of solving market failures or fixing problems that are clear, push market evolution. They commit to pushing society to the upward bend of the exponential technology curve.

Founders need to think this way. They need to understand how quickly something is going to change, and see it coming before others do. They need to convince their teammates to believe in what’s about to happen, and then they need to convince investors and beyond.

Today, our friend Azeem Azhar, former VC-backed Founder, creator of The Exponential View blog, and author of the new book The Exponential Age, gives Founders specific hooks and non-obvious ways of explaining how quickly something’s going to change — right before it does.

Below are excerpts from the released podcast episode with Azeem Azhar, in his words.

The First Exponential Age

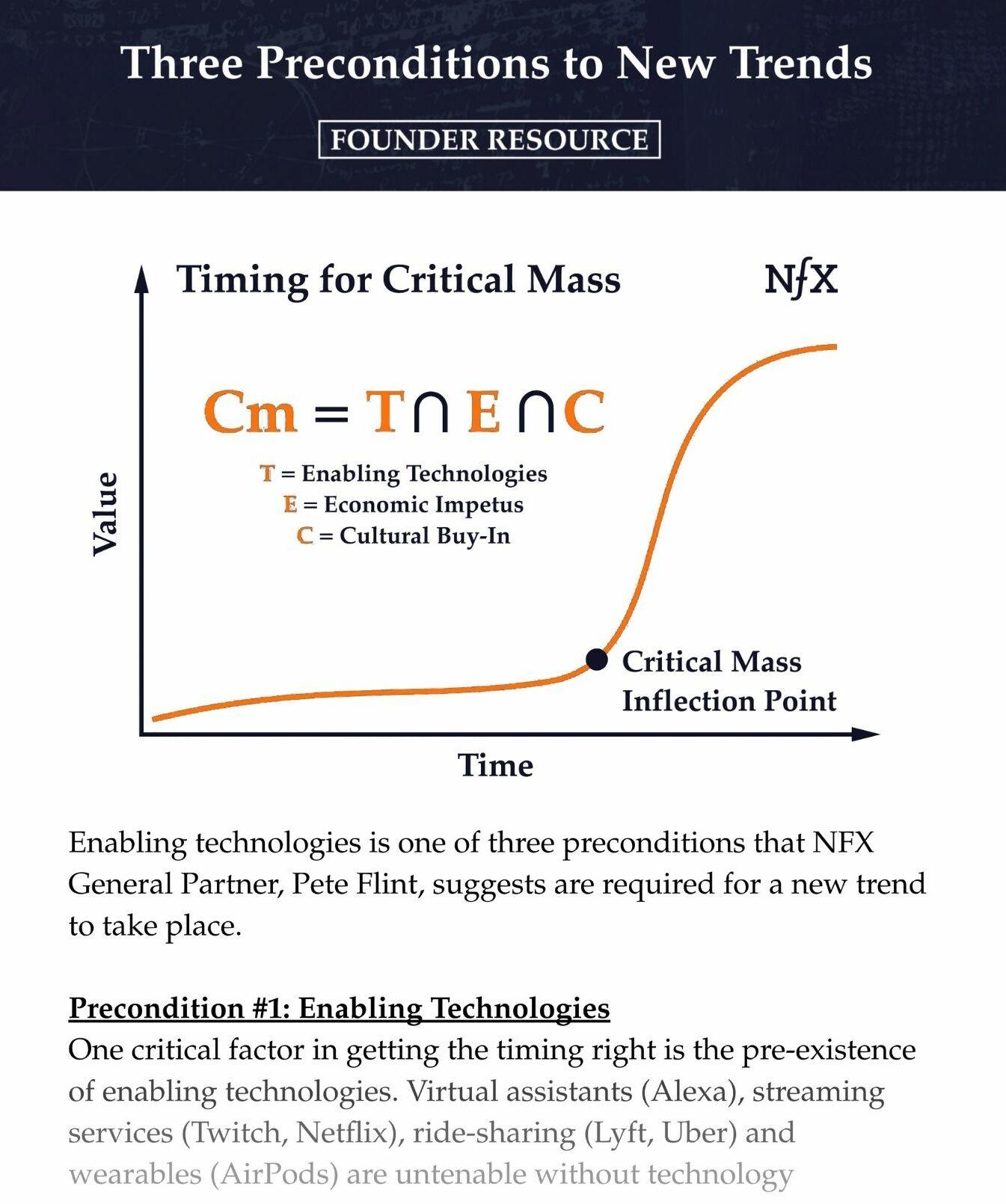

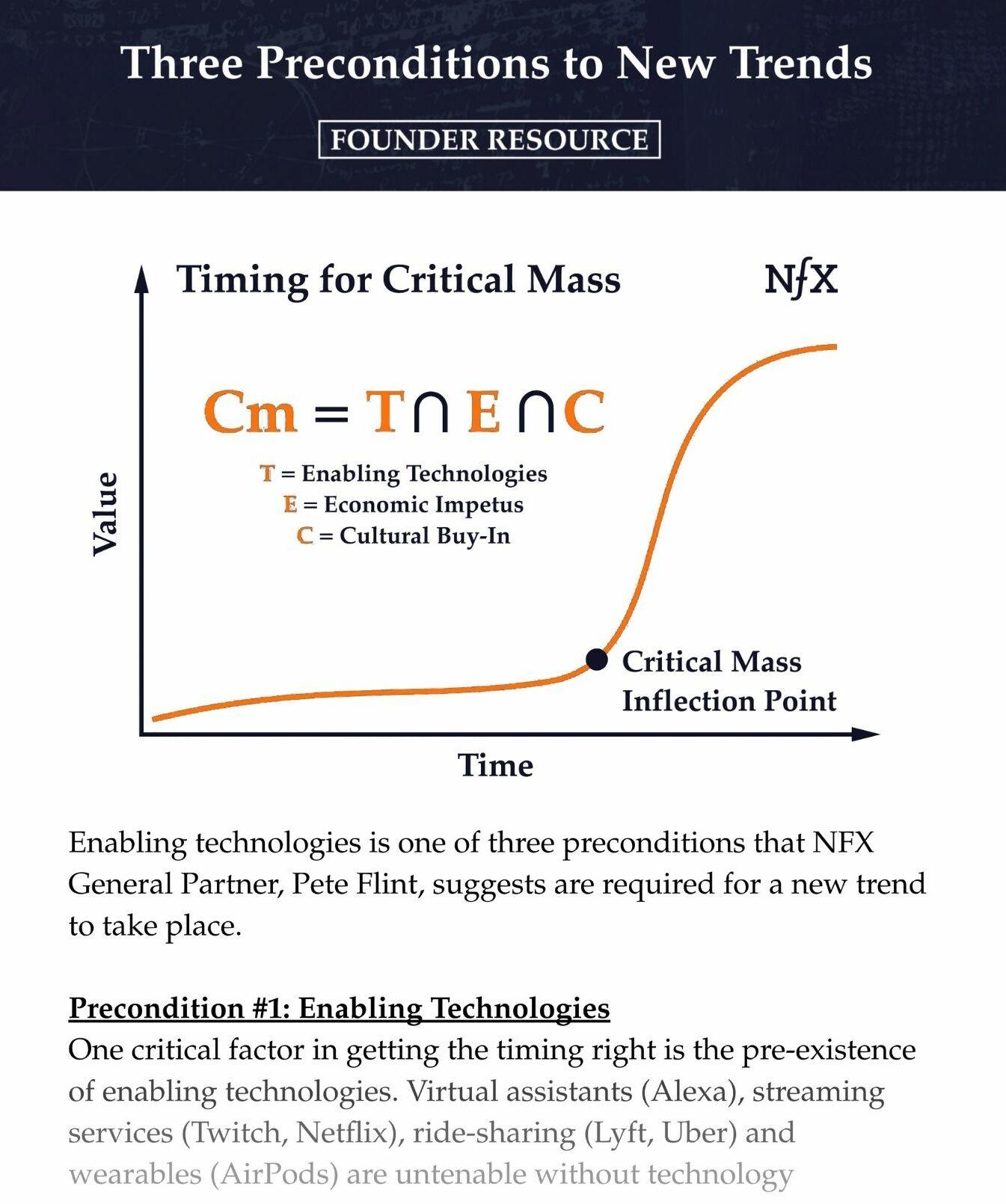

We started to see the first exponential age with the development of the internet in the late 1960s, and the Intel 4004 processor in 1971, against the backdrop of the economic ideas of Milton Friedman. As we know, with exponential curves, they start slow and they get very fast at some point. But when is that point? The question is, where does that kink in the curve happen?

I think the kink in the curve happened for society at some point between 2011 and 2015. If you go back to 2008, the world’s largest companies were all industrial age companies, Exxon, General Motors, and General Electric. By 2016, the biggest companies in the world were all exponential companies. Google, Alphabet, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon. And that’s true in China as well.

In that period of time, you start to see the smartphone become absolutely prevalent. And many other technologies start to become much more affordable. There was this 40-year running period where people in the tech industry were building, and they understood the potential of these technologies. But the first moment we could say, “We’re really reorganizing society around them,” I think is some point between 2011 and 2015.

What is an exponential technology?

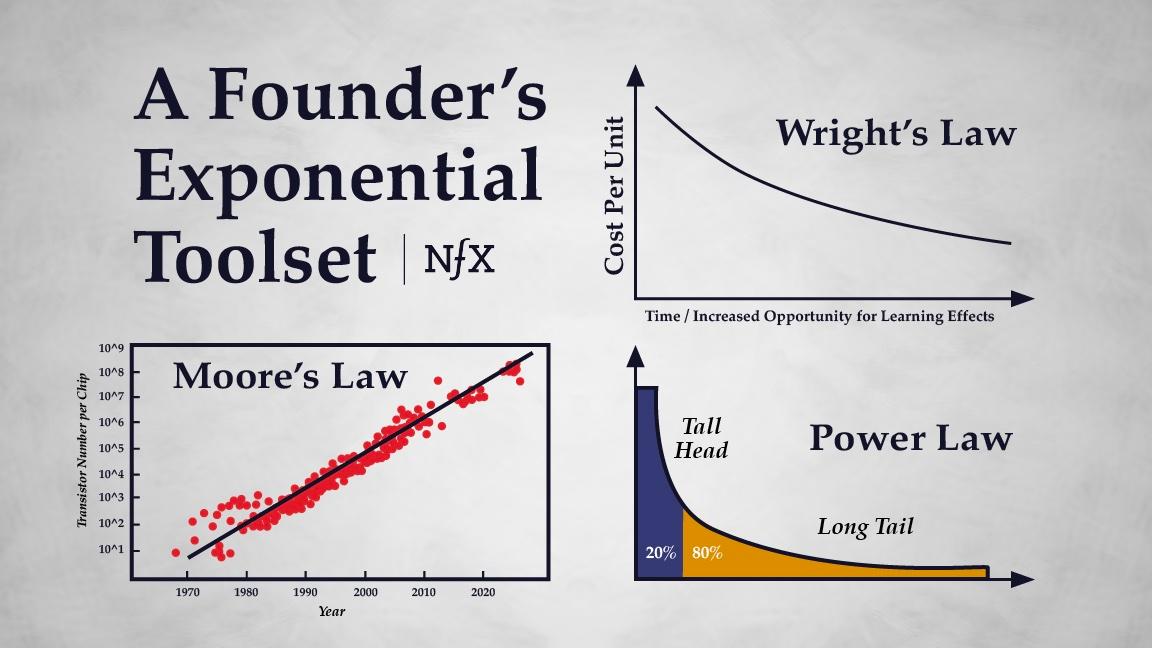

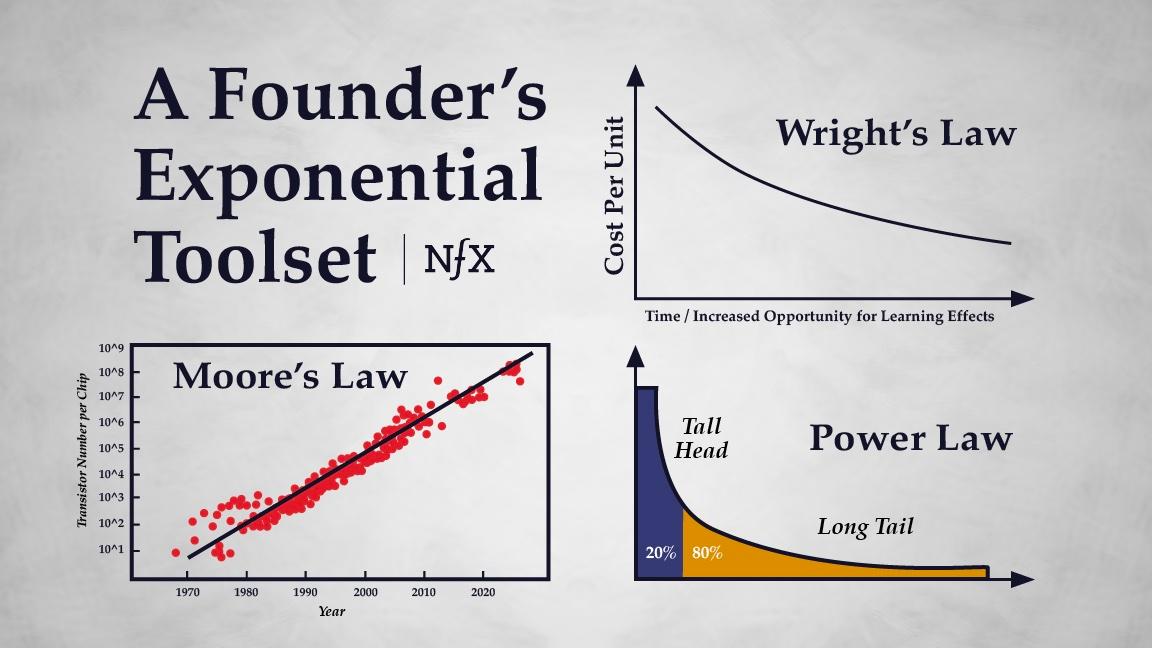

When we’re talking about an exponential technology, it’s one that improves on a price-performance basis by more than 10% per year, for many decades. The one we’re most familiar with is Moore’s law, which when you analyze Moore’s law, is a 41% improvement in performance for a fixed cost every single year. And it’s been running for 50 years.

In other exponential technologies, for example, battery storage for renewables, or in solar power generation, we see an 18% to 20% annual improvement. In the field of genomics and genome sequencing, we see an annualized improvement that is far faster than 41%.

This compounding improvement is really distinct to what we saw with the diesel engine or electricity, where these technologies at the turn of the 20th century, were improving at 1% to 3% per annum, and only did so for a few years.

The question to ask yourself is what actually happens? What does this level of improvement mean? It means that the price declines rapidly and an activity that perhaps a nation-state could contend with, becomes something that we can all do at home, in just over a few decades. And that creates incredible opportunity and incredible change.

3 Key Drivers of Exponentiality

Why does this process of exponentiality emerge in some areas of business, but not in others? We know chips have gotten much cheaper. We know disc drive storage has gotten much cheaper. We don’t use disc drives anymore, but memory storage has gotten cheaper. And we know that genome sequencing has gotten cheaper, but large-scale nuclear reactors haven’t gotten cheaper, and Boeing’s airplanes haven’t gotten cheaper. What is it about the technologies that actually get cheaper, that makes them get cheaper, and how can you choose those particular ones?

I think answering this question is an essential part of the analysis. Obviously, lots of academics have done work in this space, but I identified three key drivers. The first is the idea of learning by doing. The second is the idea of standardization and combination. And the third is something that’s slightly out of a Founder’s control, which is the idea of networks that act as accelerators and catalysts.

1. Let’s look at the learning aspect first. Moore’s law was articulated in 1965 by one of the Founders of Intel. He observed that every couple of years, the number of transistors you could fit on the same area of silicon was roughly doubling. And that would make those chips effectively twice as fast for roughly the same cost.

Moore’s Law was a description that ended up being a social fact that all of the players in the Silicon chip manufacturing business, from the photolithographers, to the people making the chemicals, to the people making the lasers, conspired over decades to make work. But Moore’s Law is not a strongly predictive law. It’s a descriptive one. There’s a better way of understanding how technologies get cheaper.

This goes back to an observation made by someone looking at how aircraft were made. Theodore Wright, in 1936, was looking at how people made airframes and he realized that for every doubling of production, the unit cost of an airplane declined by about 15%. And that wasn’t an economy of scale effect. It wasn’t that we could buy the materials cheaper because we were making more. It was the engineers, being engineers. They had figured out optimizations, and anyone who’s worked with developers knows that that’s what developers try to do.

They try to find out how to do something a bit quicker, using fewer and fewer resources. And that learning by doing is ultimately what drives the price decline in technologies.

It turns out that if you apply Wright’s Law to Silicon Chips, it’s more predictive than Moore’s Law. And if you apply Wright’s Law to a lot of other things like wind turbines, as big as they are, it’s really useful and predictive.

One of the things that I try to look for is if there’s a technology, whether it is in cellular agriculture or direct air capture: Does the way that the team is delivering this particular solution lend itself to good learning effects? If it does, then I can see them getting a cost advantage over the competitor.

2. There are some other drivers behind Wright’s Law, and they can help increase that 15% decline. One driver is my second rationale: this idea of combinations and modularity. If you have systems that are quite modular, that scale through modularity, you are more likely to benefit from learning effects.

Imagine you’re a Founder and you’re thinking about some particular technology: If scaling the technology involves literally making the single units you have designed much bigger, you have to go through a whole set of new learning about how you scale that up. But if you have something that’s modular and you get to 100X scale by taking 100 of your units and then figuring out how they coordinate, you actually get the volume effects that Wright’s Law predicts.

You’ve now got a distributed system, but you walk down that learning curve quicker than the person who’s trying to scale a monolith. Does this lend itself to a process of exponentiality that we can live off?

Sometimes there are second-order effects. If you look at what’s happened in genomics and the declining price of sequencing a human genome, there are a number of different aspects at play. One part is actually just the fact that a lot of it relies on computer storage, databases, and processing, which are going down on their own decelerating price curves.

The other thing is we’ve actually started to get better at the electrochemistry. Sometimes when you look at a particular technology and you unpick it, you realize there’s not just a single clock speed that is forcing its price to decline. There are a number of different things and sometimes they’re coming from other technology domains. But modularity is a reasonably good heuristic to use.

3. The beauty of the internet is its collective intelligence. On the internet, we have shortened the distance from idea theory to implementation with an information feedback loop. We have shortened the feedback we get about the experiments that don’t work and the ones that do work.

You can do incredible things now with the networks on the internet. You can watch YouTube videos, get code from GitHub, and the internet keeps showing up because it shares our successes and failures. From our theory that lives on the preprint servers, which is now working code on GitHub, to people discussing and showing off their implementations on Hacker News, the whole cycle is extremely compressed.

By searching around on the internet, you can go and find these bits of information and weave them together into a unique piece of art, a unique piece of technology that can make a real impact. Whereas before the distance between those two nodes was too far and it would just take too long.

You might remember the RSA encryption algorithm. This was developed in the mid-70s and it had to go through the traditional academic publishing routes, and after that, it was IP protected. It really didn’t become commonplace for 20 to 25 years. That was the amount of time it took for ideas to go from brilliant academics to having a positive impact in the world.

Today, we can absolutely shorten that. Now, it’s not just the fact that GitHub exists and we have forums that work effectively. It’s also about technology transfer out of universities, venture capital firms, and incubators.

Technology Evolves with Society

There is a lot of resilience and creativity that comes through the tech industry. But I also believe that these products and technologies were going to happen anyway.

I think the media and the storytellers need people to anchor on, so they tend to anchor on personalities. But technology evolves with society.

The idea that you’re part of an inevitable process rather than a great person of history is a really important one to grasp and to grapple with. But it’s also important to understand what the political backdrop has been.

The recent history of the technology industry, the period from the 70s to now, took place against the backdrop of a particular type of politics. And that politics was initially informed by Milton Friedman’s idea that the purpose of a corporation is only to make profits for its shareholders, as long as it stays within the rules of the game.

In the US and in the UK, we went into this mode where we stripped out a lot of onerous regulations and we tackled trades unions. We essentially put the entrepreneur and the business person front and center. And that transformed into this idea about what the whole world should look like.

We got this idea of globalization with the absence of trade tariffs. We ignored a lot of other signals that were going on at the time. Some of those signals were environmental. Actually, the date that I pin to the start of the exponential age also pins to the start of the environmental movement, 1968 to 1972.

We developed the technology industry against the backdrop of this economic and political framework. And we’re now at a different point. We’re at a point where we have this very challenging climate situation we need to tackle. We also have a recognition that neoliberal consensus that helped get us here isn’t functioning according to its design. The idea of trickle-down economics largely has been agreed that it doesn’t work.

I think Founders being people who construct the future need to be more aware of the creations that they are fostering and stewarding into mass and widespread use. I don’t think this will stop great products coming to market, but I think that what it can do is it can tackle some of the negative ramifications that will emerge.

The Exponential Gap

Traditionally, for hundreds of years, we’ve thought of entrepreneurs as rushing headlong towards shareholder value, then the government steps in to make things okay. But the fact is that in the past, the technologies and the approaches that entrepreneurs were using were more linear, like the government is linear today.

But now, it’s an unfair fight, because these profit-seeking companies are operating on exponential planes. But the government is still linear, whether it’s the FAA with drones, the SEC with crypto, or the FDA with drugs. They’re still linear while everything else going on around them is now suddenly exponential.

The hot points that we’re seeing in society now tend to be this clash between the linear process of government trying to make things right, as a result of the exponential processes of these entrepreneurs.

If you imagine two lines, the exponential line racing ahead and the linear line below moving along quite slowly, I think it’s too much to ask that we stop the speed of the acceleration. That process of acceleration emerges in a very decentralized way with lots of people expressing needs and lots of people trying to figure them out. What we can do is we can raise the line above and we can get it to be much more flexible, much more resilient.

Part of this is really tactical. It’s about, how do you get people who understand this exponential gap back into public service? Getting entrepreneurs working with regulators can be helpful, but partly I think the argument is more that we need a new set of principles that replace the simple idea of shareholder value and shareholder maximization. And the benefit of principles is that we can just decide to adopt them.

They’re not like laws of physics. They are about social consensus. They’re about people buying into this idea that we need to do more. To take care of more shareholders other than stockholders.

We Need More Nimble Institutions

It’s going to be a challenge for the government not to shut these exponential technologies down and control them as the number of people involved grows to everyone. When you were talking about the internet in 2000, there were only 100 million people on it, so it was easier for the government to be hands-off. I think the question now is how do they choose to make interventions?

Institutions naturally respond very slowly. I’m hoping to give them guidance with my new book, The Exponential Age, to look at the right spots. Where are the problems really showing up and how do we get to the core of the issues?

I think the second thing they need to do is tool up. They need to be able to get the right talent. They are slowly starting to do this. Better people are starting to move into, perhaps not politics, but certainly into the regulatory environment. For example, I’ve seen this in the UK regulators and you look at someone like Lena Khan, who understands, in quite challenging terms, the nature of Amazon’s business and she’s now running the FTC in the US.

Another thing that they need to do is take a lesson from the startup book, which is the lesson of agility. Regulators are often thought of as being really inflexible. But the way they think about things now is very different. They are starting to think about this balance between allowing a company to innovate and experiment without putting too many onerous requirements on them.

What we’ve started to see in many parts of the world is the idea of sandboxes. Regulators like the Monetary Authority of Singapore and the Financial Conduct Authority in the EU are creating sandboxes where they say to FinTech startups, “You can play around and we are going to not worry so much about your regulatory requirements in return for you telling us what you’re going to be doing. And that way, we can figure out how the regulations need to change.” I think that we are starting to see some regulatory innovation. But, of course, it needs to go faster.

It’s even more important today to get regulations right because technology matters in a way that it didn’t in 1990. If Adobe had gone out of business in 1991, some shareholders would have lost money and some employees would have had a bad experience, but life would have continued. That’s just not the case now.

If something goes wrong with Netflix, Tesla, or Apple, it’s like Alderon being hit by the Death Star. There’ll be a million voices screaming in the wilderness. Consumers will not be able to conduct their everyday lives, because their car won’t drive and they won’t be able to book an appointment with the dentist. Technology is now the infrastructure of society.

One of the perhaps more contentious ideas that I put out there is that if you’ve got a company that is behaving, and through its own efforts has created an essential facility that has a network effect that pervades society, it’s a utility. And we treat utilities across the world differently to the way we treat things that are not utilities. They have higher obligations. They often have their prices regulated and their profits regulated.

There could be some future mechanism we create for these situations. The question then is, does that actually harm the journey of the entrepreneur? My argument would be that it doesn’t, you can still make outstanding, generational returns well before you get to that stage.

We Can’t Avoid The Power Law

We can’t avoid the power law, unfortunately, with these exponential technologies. Once you get to markets that are bigger and bigger, you’ll see that power law accentuates and exacerbates.

Once you recognize, as a particular nation, that power laws are operating with economic and political rewards, you then have to figure out what is culturally acceptable in your country. That culturally acceptable solution might be higher taxes, it might be higher inheritance taxes. It might be some form of universal basic income. It might be the fact that you may neutralize part of a business because it gets too big and too successful. But it does require some intervention because otherwise, you get into this arena of really deep political risk.

I think there’s another dynamic that’s quite interesting. What if we could do a good job with this idea of cooperative collective spaces? One of the areas that I think about is health data.

If health data can be widely shared and aggregated, but not in the way that we do with our social data on Facebook, where essentially Facebook owns it all and monetizes it as a monopolist and makes incredible profits from it. But if our health data can be shared in a way that is sympathetic to our own privacy needs. We still get the collective aggregate benefit for developing new products and services, then we can all start to benefit and the baseline starts to rise.

We’ve started to see experiments like this happen. In the UK, for example, it’s administratively quite clunky, but it’s interesting to see all of the chest x-rays and CT scans of people with COVID are now being aggregated in a semi-common repository. Now, any researcher can come in and take a look at them, and then build an algorithm or do research off it.

In the US, there is an example from the days of the Westward expansion. In the late 19th century, steelmakers couldn’t produce steel fast enough for the amount of rail track that needed to be laid, so they got together and started to share their patents and their know-how. It was called a process of collective invention. Although this ultimately ended up with these grand family fortunes being made in the Gilded Age, it actually started with entrepreneurs coming together and saying, “Let’s share this know-how because we’re stronger together.” And the internet, theoretically, should support that more and more.

New Economics and Governance

If we look back at the history of travel, the very first ventures that went out, which would have been a few hundred years ago, were seafaring expeditions. On the expedition, the typical sailor got nothing but scurvy.

As we moved forward, you started to see, “Well, the provider of the capital and the owner will take most of the rewards, but the employees will be paid better.” Then we started to introduce the idea of stock ownership and stock option plans. Now, companies commonly distribute their wealth across a wide range of stakeholders. Silicon Valley was at the forefront of this.

There is this progression that we see historically, and I’m excited that crypto will help push us further in that direction over the next 10 to 15 years. These are the new frontiers of governance that we haven’t had to think about, but will start to emerge. Crypto not only shares the economic benefits, but it also can, if it’s built correctly, share the governance benefits. The power to decide where this thing goes.

I think it’s a really fascinating possibility that we could go off and create these mini markets, met with the arrival of tokenization that allows us to participate and enjoy some of the economic rewards.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.