In 1956, a North Carolinian trucker named Malcolm McLean stood on a dock in Newark and watched longshoremen load cargo onto a ship the same way the Phoenicians had done three thousand years earlier – one crate, one barrel, one sack at a time. It cost $5.86 per ton. Six months later, McLean loaded 58 aluminum containers onto a converted WWII tanker using a crane. It cost 16 cents per ton.

McLean didn’t invent the container. What he invented was the system – redesigning the containers, the ships, the cranes, the ports, the truck chassis, and the rail connections simultaneously, so that a single standardized unit could move seamlessly from factory floor, to ocean freighter, to railroad, to warehouse without ever being opened.

Seventy years later, SpaceX landed a Falcon 9 booster on a drone ship in the Atlantic. Rockets had existed for decades. Reusability had even been attempted. The Space Shuttle was technically reusable at a cost of approximately $1.5 billion per flight. But just like McLean, SpaceX rethought the system: design for rapid reuse from day one, vertically integrate manufacturing, iterate through flight and failure rather than paper plus committee. The idea wasn’t new, but the system-level integration was. Launch costs have been on a downward trajectory since then.

This is not a coincidence. Once you start designing systems – and thinking in them – previously unapproachable feats become possible, and new markets are created. It is one of the oldest patterns in economic history. And if you understand how it’s played out before, you can start to see what’s coming next.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

The Historical Power of the “Cost Collapse” Pattern

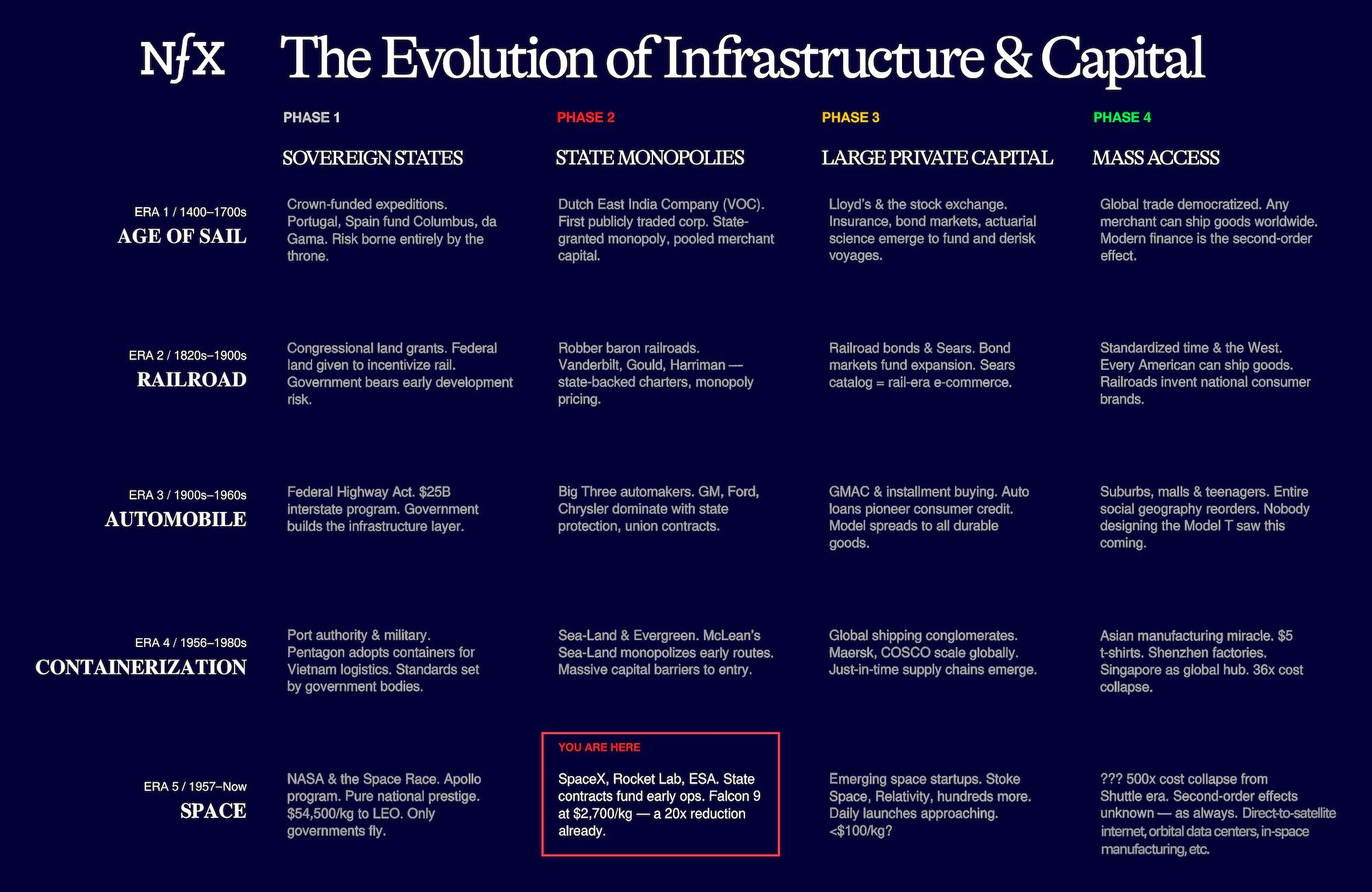

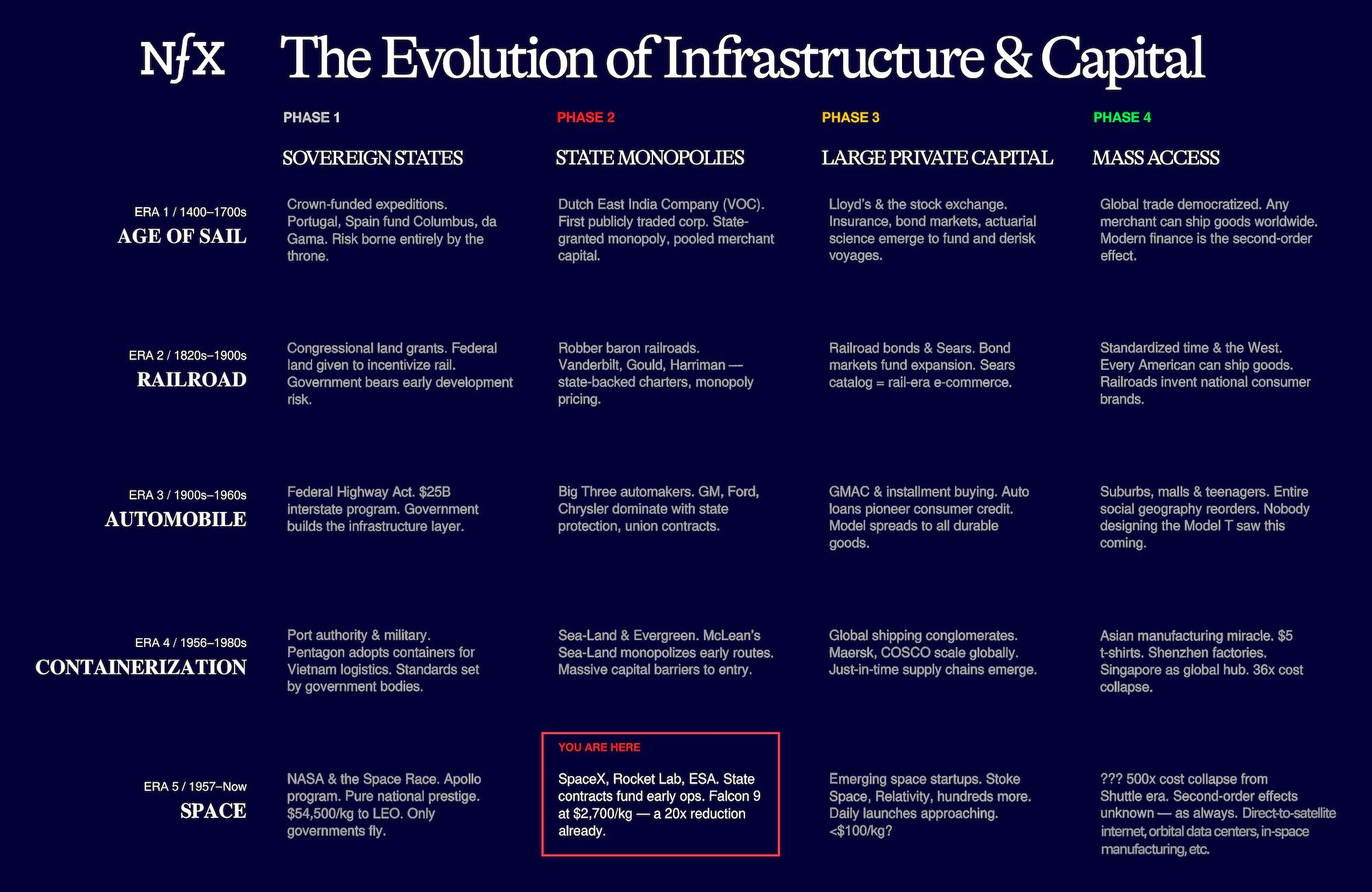

Every transformative era in transportation follows roughly the same sequence:

- An enabling technology makes movement dramatically cheaper, faster, or more reliable.

- A cost collapse follows, & unit economics shift by an order of magnitude.

- Access to goods & services democratizes – what was exclusive to the elites becomes available to merchants, then to the masses.

- New industries, institutions, and social structures emerge that nobody predicted.

- Power reshuffles – sometimes new geopolitical powers rise, sometimes existing ones compound their lead, but the incumbents who assume their advantage is permanent almost always lose it.

This pattern has repeated at least four times. Each time, the people living through it dramatically underestimated the cost collapse’s potential, and only a select few had the vision to see the second and third order effects it would eventually create.

Here are some examples:

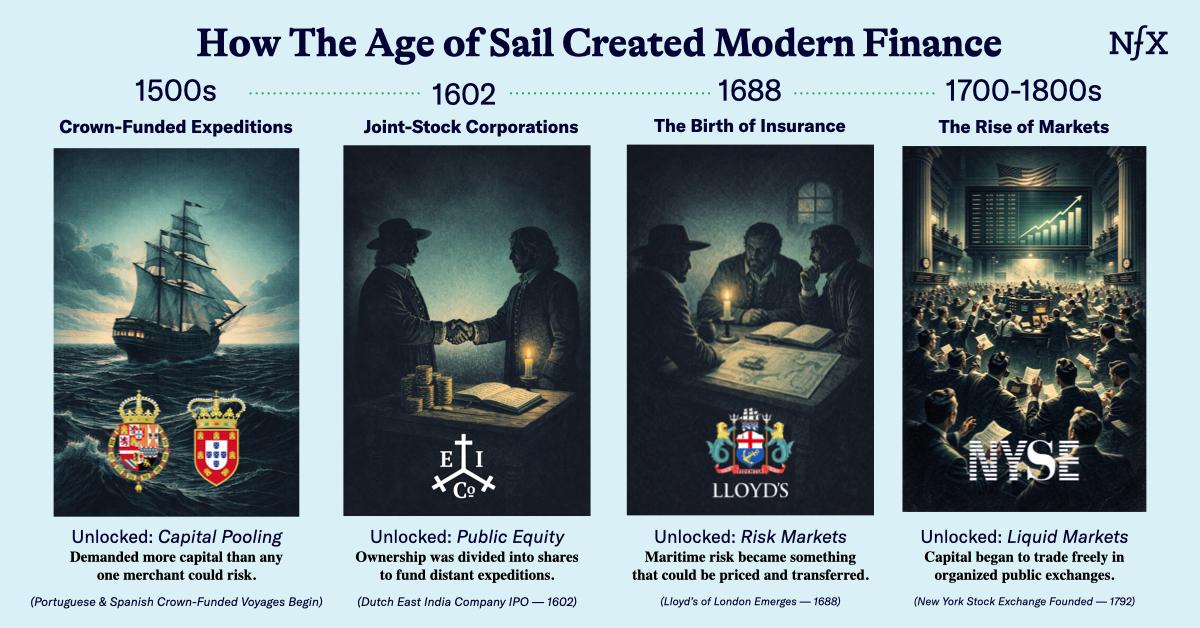

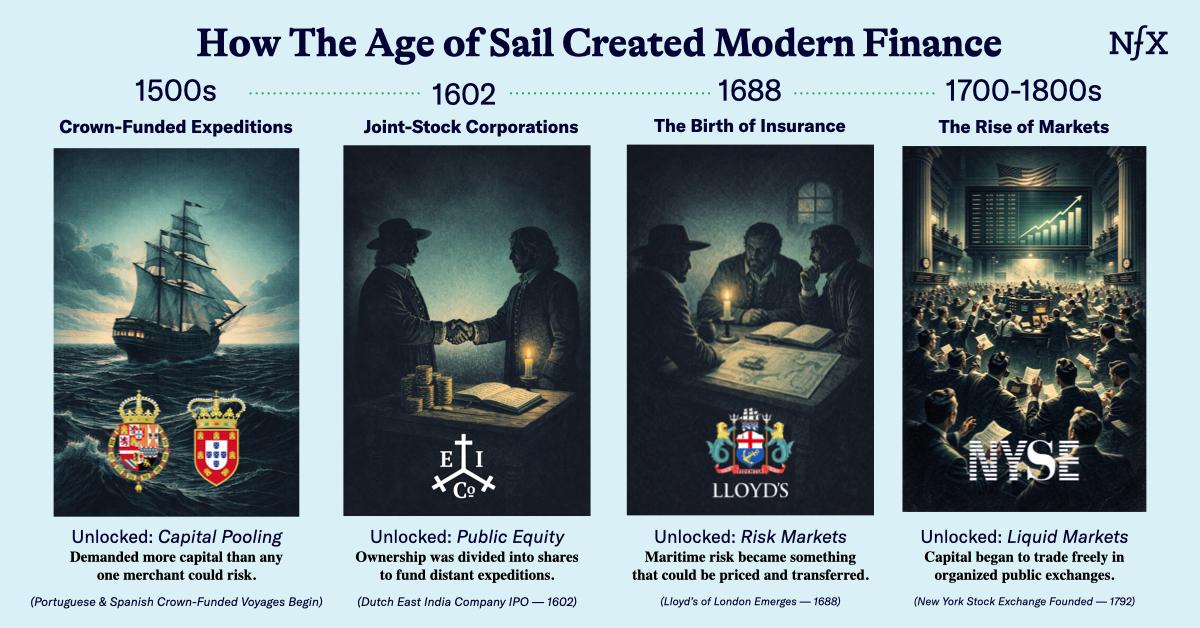

The age of sail gave us modern finance. When Portuguese and Spanish ships first crossed oceans in the 15th and 16th centuries, the voyages were funded by sovereign crowns. The risk was enormous, and the capital requirements were beyond the means of any individual merchant. The solution was to pool capital from many investors, share the risk, and share the returns.

The Dutch East India Company is widely regarded as the first publicly traded corporation, established to address a transportation financing problem. Lloyd’s of London, the pioneer of modern insurance, began as a coffeehouse where ship insurers gathered to price maritime risk. Stock exchanges, bond markets, and actuarial science – the entire architecture of modern finance traces back to the need to fund and derisk ocean voyages. The ships were the technology. The financial primitives were the second-order effects.

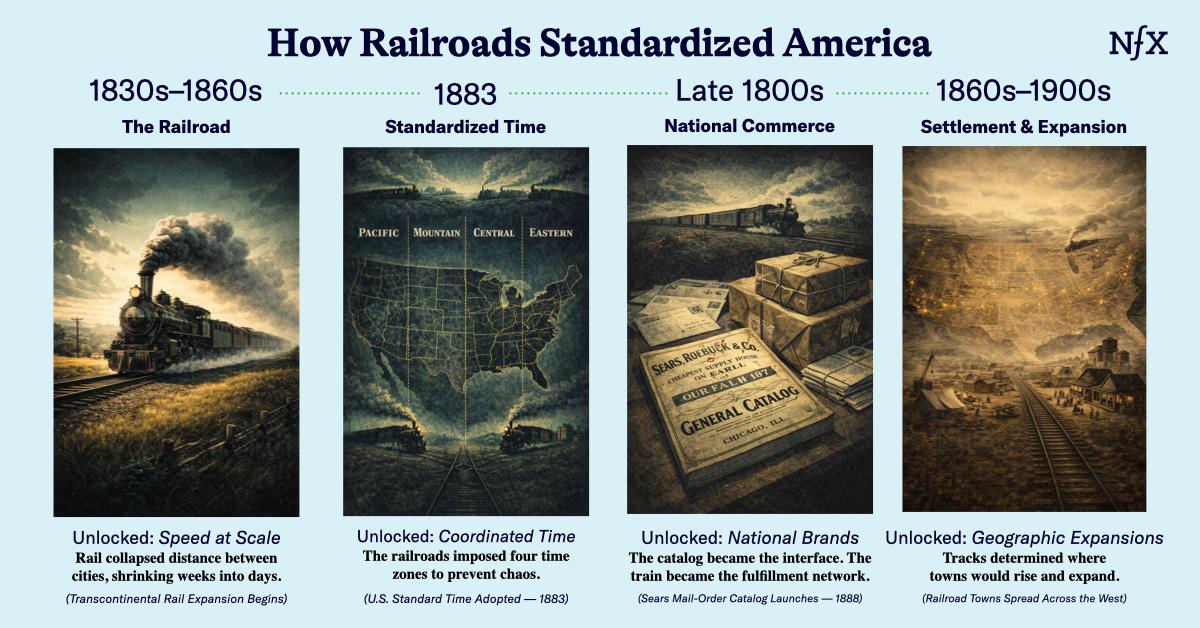

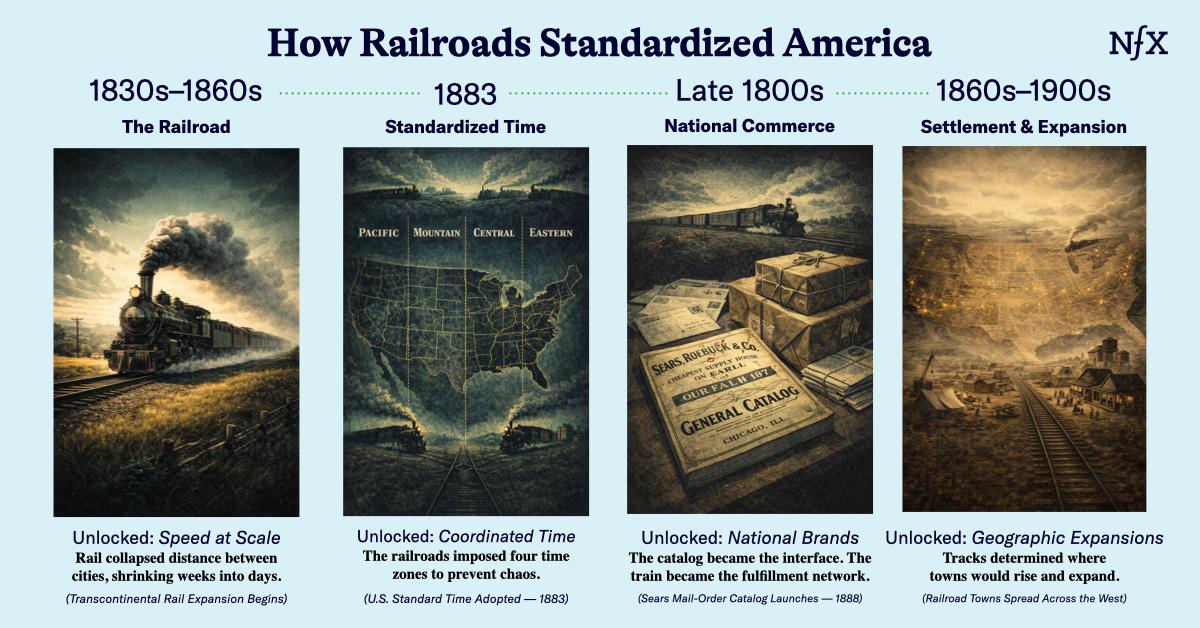

The railroad invented standardized time. Before rail, every city in America set its own clock by the sun (yes, really). Noon in Chicago was different from noon in Pittsburgh. When the fastest thing moving was a horse, this was sufficient. Enter the railroad. The rapid reduction in travel time, combined with nonstandardized time zones, meant chaos when it came to publishing a train schedule.

In 1883, the railroads (not Congress, not the President) imposed four standardized time zones across the United States. The system simply demanded it. Railroads also created the first national consumer brands! Sears was essentially a railroad-era e-commerce company – the catalog was the interface, rail was the fulfillment network. Railroads also settled the West and bore new towns into existence. The track came first, the town followed.

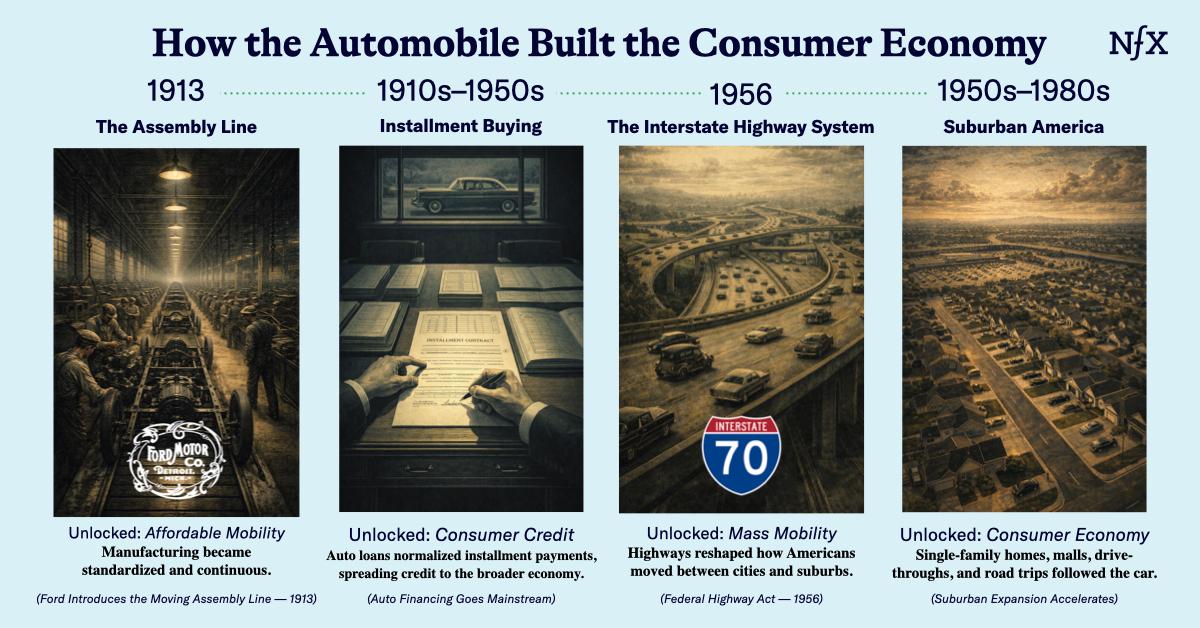

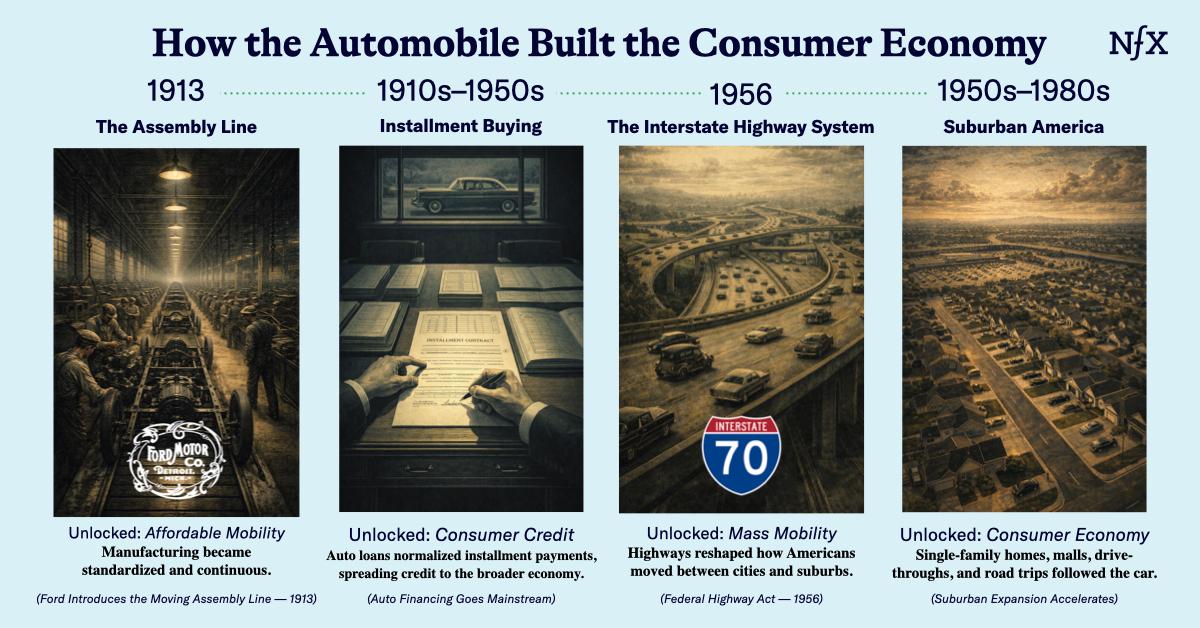

The automobile restructured where and how people lived. The car’s most consequential effects were both social and economic. Suburbanization, the single-family home, the two-car garage, consumer credit, the shopping mall, the motel, the road trip, the drive-through, the teenager’s freedom from parental oversight – these are all downstream of Henry Ford’s assembly line and the Federal Highway Act. The automobile also created demand for installment buying (auto loans), which then spread to other goods (yes, that means you have Mr. Ford to thank for being able to BNPL your Chipotle burrito). The modern consumer economy is based on a financing model pioneered by the automotive industry. Nobody designing the Model T in 1908 was thinking about suburban sprawl or consumer credit. Not bad for a horseless carriage!

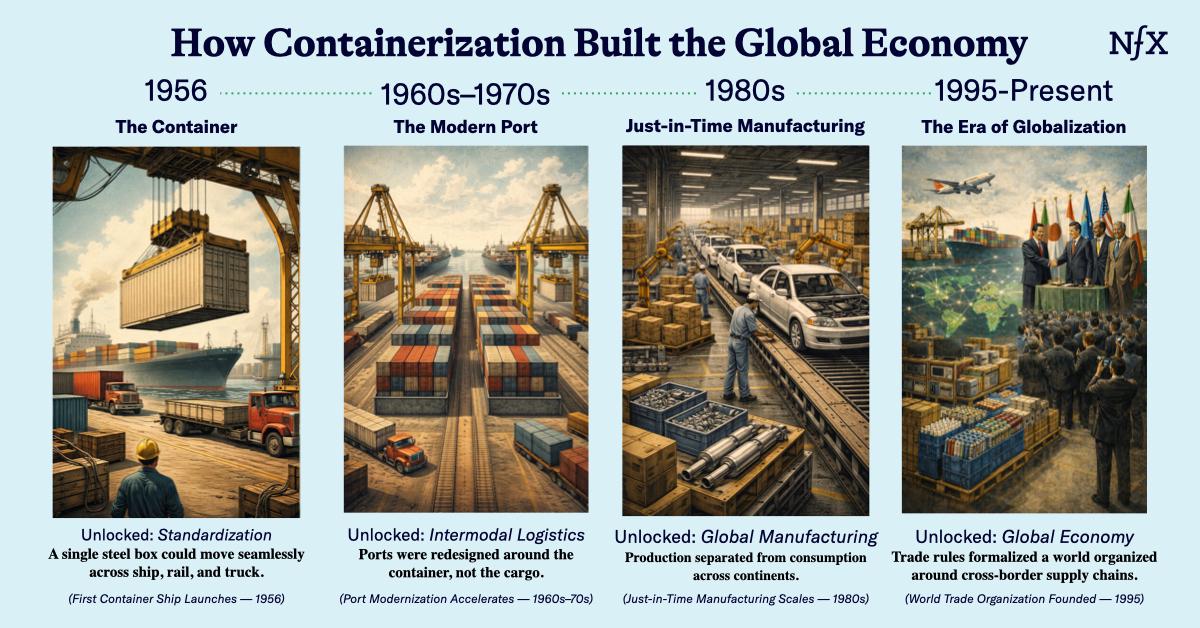

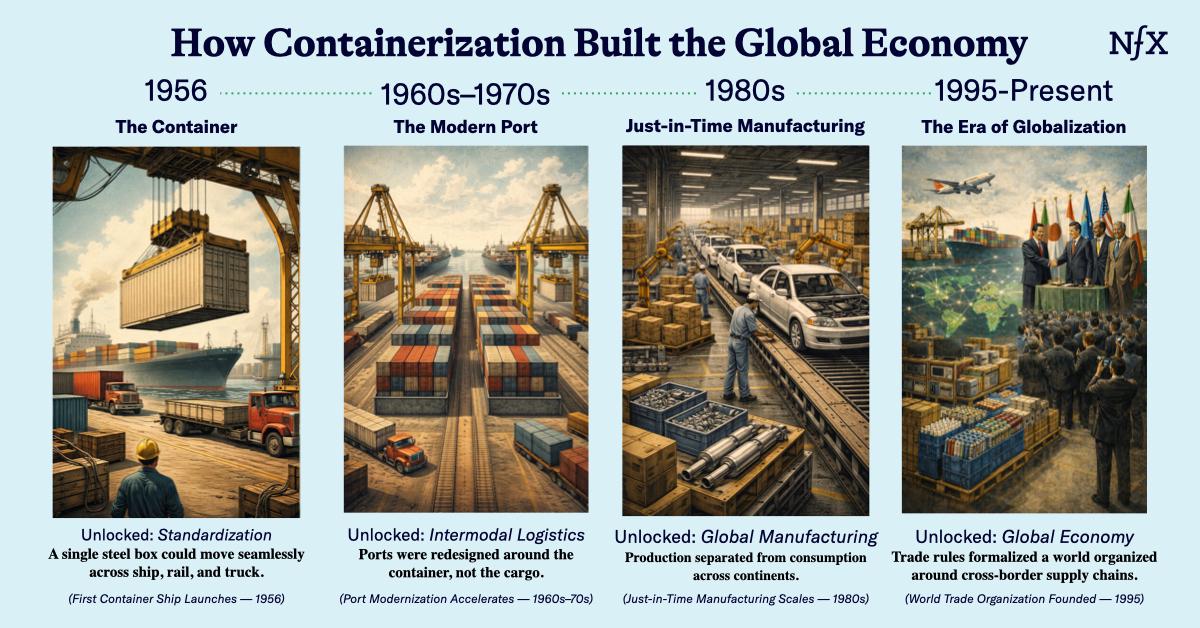

Containerization enabled the globalization of manufacturing. The container made it economically viable to separate production from consumption. That single shift created the Asian manufacturing miracle, just-in-time supply chains, the offshoring revolution, and the entire modern consumer goods economy. It also destroyed entire communities – traditional dock workers, break-bulk ports, and cities that failed to modernize their harbors. The container was a steel box. The second-order effect was the reorganization of the global economy.

The enabling technology matters enormously. But it’s never where the story ends. Every transportation era is remembered not just for the ship or the engine or the box, but for the world it accidentally created. The second-order effects are always bigger than the first-order technology, and they’re usually pretty surprising.

Space is following the same pattern.

Which brings us to our next question: where are we in the process today?

The Container and the Rocket

Containerization is the closest analog to what’s happening in space right now.

Before the container, shipping was an artisanal trade. When McLean recognized that paradox, his system collapsed those costs by ~36x. That’s great on its own, but the bigger point is what the 36x enabled. Once it cost almost nothing to load a ship, it suddenly made economic sense to manufacture goods on one side of the planet and sell them on the other.

The economic viability of long-distance manufacturing arbitrage is the reason a factory worker in Shenzhen assembles your phone. It’s the reason Singapore went from a modest colonial port to a global financial hub, and it’s the reason you can buy a t-shirt for $5.

No one would have predicted those changes from looking at a container. You had to stare at the cost curve of long-distance manufacturing and ask: what becomes possible when this approaches near-zero?

Now look at space. The Space Shuttle launched a payload to LEO at roughly $54,500 per kilogram. Falcon 9 does it for ~$2,700 – a 20x reduction. Falcon Heavy pushes it to ~$1,500 per kilogram – a 36x reduction. For those keeping track, that’s the exact same magnitude as containerization (eerie, we know).

And Starship, if it achieves even a fraction of its target economics, should push costs below $100 per kilogram. That’s a ~500x reduction from the shuttle era.

Other companies will take this a step further still. Stoke Space is designing rockets for a 24-hour turnaround between flights. If a rocket can fly daily, launch stops being an event and becomes infrastructure – a system.

That’s the same leap McLean made: not just a better box, but a system so fast and standardized that the bottleneck disappears entirely.

A 36x reduction in transport costs was enough to reshape the world’s economy in the 18th and 19th centuries. Imagine what a 500x change in cost and daily launch capacity would unlock today?

The Democratization Sequence

The cost collapse is underway. The question, as always, is: what will it enable?

The specifics are likely unpredictable to us today, but categorically (thanks to the cost collapse pattern), we can make a broad prediction: the expansion of goods and services.

The question is how fast this will roll out and what shape it will take. There, too, history reveals a pattern.

If you look really closely at our cost-collapse sequence, you’ll see another layer: the capital. The sources of capital often change as we move through each step. It starts with sovereign states, moves to state-backed monopolies, then to large private capital, and then to mass access.

Space is no different. But from a capital perspective, we are arguably still in the state-backed monopoly phase. It has transformed the industry. There’s no belittling that. But it’s a shadow of what a fully democratized space economy can produce – of the industries, institutions, and geopolitical reordering that would follow.

These returns will only arrive if the democratization wave continues to accelerate. If more people can raise capital, test ideas, and experiment on the leading edge of the space economy…that is where the second and third-order effects come from.

If the age of sail had stopped at sovereign crowns, we would never have had modern finance, global trade, or the Industrial Revolution that followed. If Henry Ford had built the Model T but never the assembly line, the car would have stayed a rich man’s novelty – no suburbs, no highways, no consumer economy.

The ingredients for innovation and expansion in space is all right there. If we allow democratization to happen. We need to move from ‘only large private players dominate’ to ‘anyone with a payload can participate.’

Our investments in the space economy are largely focused on that potential future. To unlock second and third-order effects, we need a fully developed infrastructure and agile capital allowing ideas to complete at each open layer. It creates a greater surface area of ideas.

Cost collapse initiates the expansion of goods and services. But investing in the democratization of the space economy is like pouring fuel on a fire. This is happening. But we, as investors, can do a lot to make it fully realized.

Right now, we’re at the equivalent of containerization in the late 1960s – the system works, costs are falling fast, but the full democratization wave hasn’t hit yet. We want to be on the leading edge of that wave.

Infrastructure Comes First, Imagination Follows

Some second-order effects of cheap space access are already here.

Satellite broadband is one – Starlink alone has ~10,000 satellites in orbit – is connecting places that terrestrial infrastructure never reached.

Earth observation is becoming sufficiently persistent and granular to monitor crop health, supply chain flows, and military movements in near-real time. GPS and its derivatives are so embedded in modern life that a single day of GPS failure would cost the U.S. economy an estimated $1 billion, so companies like EarthTraq are building the next generation of PNT tech.

When space infrastructure matures beyond its first generation, services become cheaper, smaller, and more ubiquitous, and begin to appear in use cases the original architects likely never imagined.

We see some already emerging. Orbital data centers, where solar power is abundant and uninterrupted, are being actively developed. In-orbit manufacturing – using microgravity to produce pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, & more – is moving from laboratory experiments to early commercial operations.

The formation of servicing innovations is also a big one. Every transportation network in history required a servicing layer before it could truly scale (gas stations, tow trucks, highway maintenance crews, etc) – and that servicing layer, in turn, changed the economics of everything else on the network.

In space, that layer is being built now. Starfish Space is developing vehicles that can rendezvous with satellites in orbit, extend their operational lives, reposition them, or safely deorbit them at end-of-life.

This matters more than it might appear. Once on-orbit servicing exists at scale, the economics of everything else in space change. Operators can build more cheaply, plan more flexibly, and insure at lower cost.

A single geostationary communications satellite costs hundreds of millions of dollars; extending its life by even a few months fundamentally alters the ROI. Multiply that across tens of thousands (& counting) of satellites and servicing becomes an enormous market.

It’s the layer that doesn’t generate headlines, but it’s also the layer that has to exist before the second and third-order effects can become realities. The servicing layer is what kicks off the network effects.

Today, we can see enough activity to show us that the process of cost collapse is already working. But we know it’s about to accelerate. And that means that the most important applications of the future are still probably the ones we don’t have names for yet.

People must first see what’s possible before truly innovative creativity kicks in. The railroad had to exist before Sears could imagine a catalog business. Container ships had to be sailing before anyone could envision globally distributed manufacturing.

The infrastructure comes first, and the imagination follows.

This is Inevitable, For Someone

The rise of the new space economy is not a matter of if or when. It is a matter of who will be best positioned to benefit.

Currently, the U.S. has a compounding advantage: equator-adjacent launch sites, a deep aerospace talent pool, mature regulatory infrastructure, the world’s most active capital markets for space ventures, and a head start in reusable launch that no other nation has matched.

That advantage is real. But so is its half-life. The historical pattern is unambiguous: every era’s early geographic winner eventually faces challengers. China is investing heavily in reusable launch. They’re also building orbital supercomputers. India’s space program is growing rapidly.

The U.S. has perhaps a one or two-decade window of unique advantage in space. Whether it builds durable institutional and infrastructure moats in that window – or assumes, as many fallen empires have, that the lead is self-sustaining – will matter enormously.

The enabling technology exists. SpaceX and others have built the equivalent of the Model T and the beginnings of the assembly line. But the roads, the gas stations, the dealerships, the financing infrastructure? That’s all still being built. The full ecosystem that will turn cheap access into a full-fledged space economy – launch providers, orbital servicing, in-space infrastructure, and the private capital to fund it – is still early.

This revolution is going to happen, with or without the U.S. at the center of it. The pattern is too consistent, the cost curve too steep, the incentives too strong. China, India, and others aren’t waiting around. The U.S. has a lead. It doesn’t have a lock. And the history of transportation is littered with early leaders who mistook a head start for a moat.

To Wrap This Up

We’ve studied this pattern closely. At NFX, we’ve backed companies building across the space infrastructure stack: launch, on-orbit servicing, positioning and tracking, and orbital computing. We can’t predict exactly which second-order effects will emerge – history teaches us that’s a fool’s errand – but the pattern itself is legible.

Cost collapses of this magnitude always generate transformative industries. The enabling layers must be built before those industries can materialize. And the window for building them is finite.

Every transportation revolution in history has followed the same sequence: an enabling technology, a cost collapse, a democratization of access, an explosion of industries nobody predicted, and a reshuffling of geographic advantage. The people who built the infrastructure – the ports, the rail depots, the highways, the container cranes – generally did quite well. Those who waited for the second-order effects to become obvious arrived too late.

Space is running the same machine. The cost collapse is underway. The democratization is beginning. And the most consequential effects are still ahead.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.