Media marketplaces are businesses that monetize attention.

They connect content producers with audiences. Sometimes revenues come from advertisers, sometimes audiences pay, sometimes both. The first media marketplaces were newspapers that ran ads starting in 1625.

In the most recent 20 years, digital media marketplaces have become some of the most iconic names in consumer tech. You might not think WhatsApp and Netflix are in the same category, but they are when you look at the underlying mechanisms.

Because people continually long for novelty and new forms of content, media marketplaces are still possible to build.

Now is a great time to build a media marketplace. Not only are the audiences now in the billions, but subscription-driven media marketplaces are becoming viable again. Evolving payment options on mobile and the ease to connect with micro-markets through other media marketplaces make subscriptions newly powerful.

Are micro-markets interesting for creating iconic companies? Sure. Photo-sharing for college students looked like a micro-market when it first started.

Today, we want to give Founders the frameworks to empower the next generation of media marketplaces.

Even if you aren’t building a media marketplace, seeing how they work and the frameworks beneath them will help you better understand the world we live in today.

The Unique Network Effects of Media Marketplaces

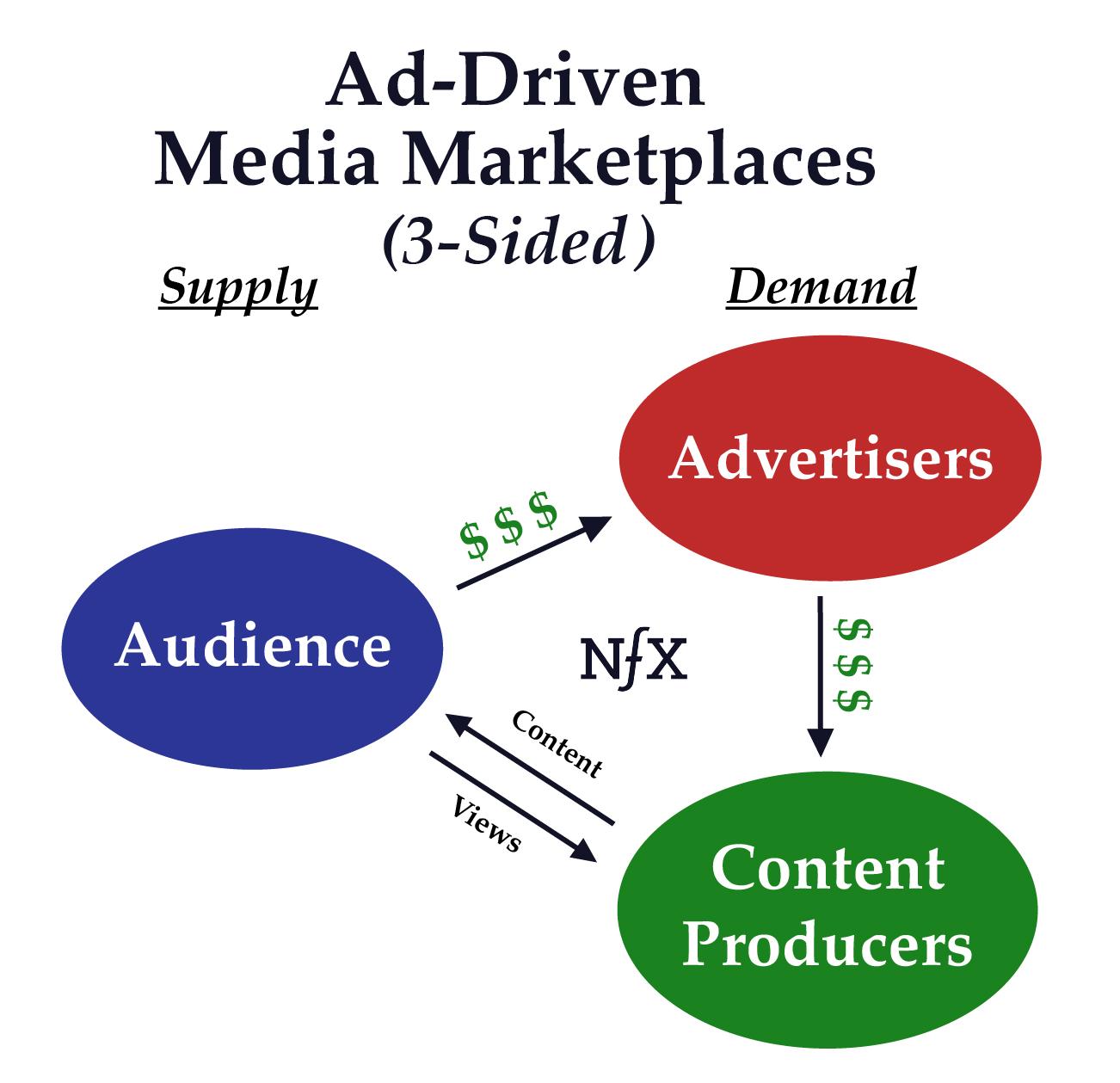

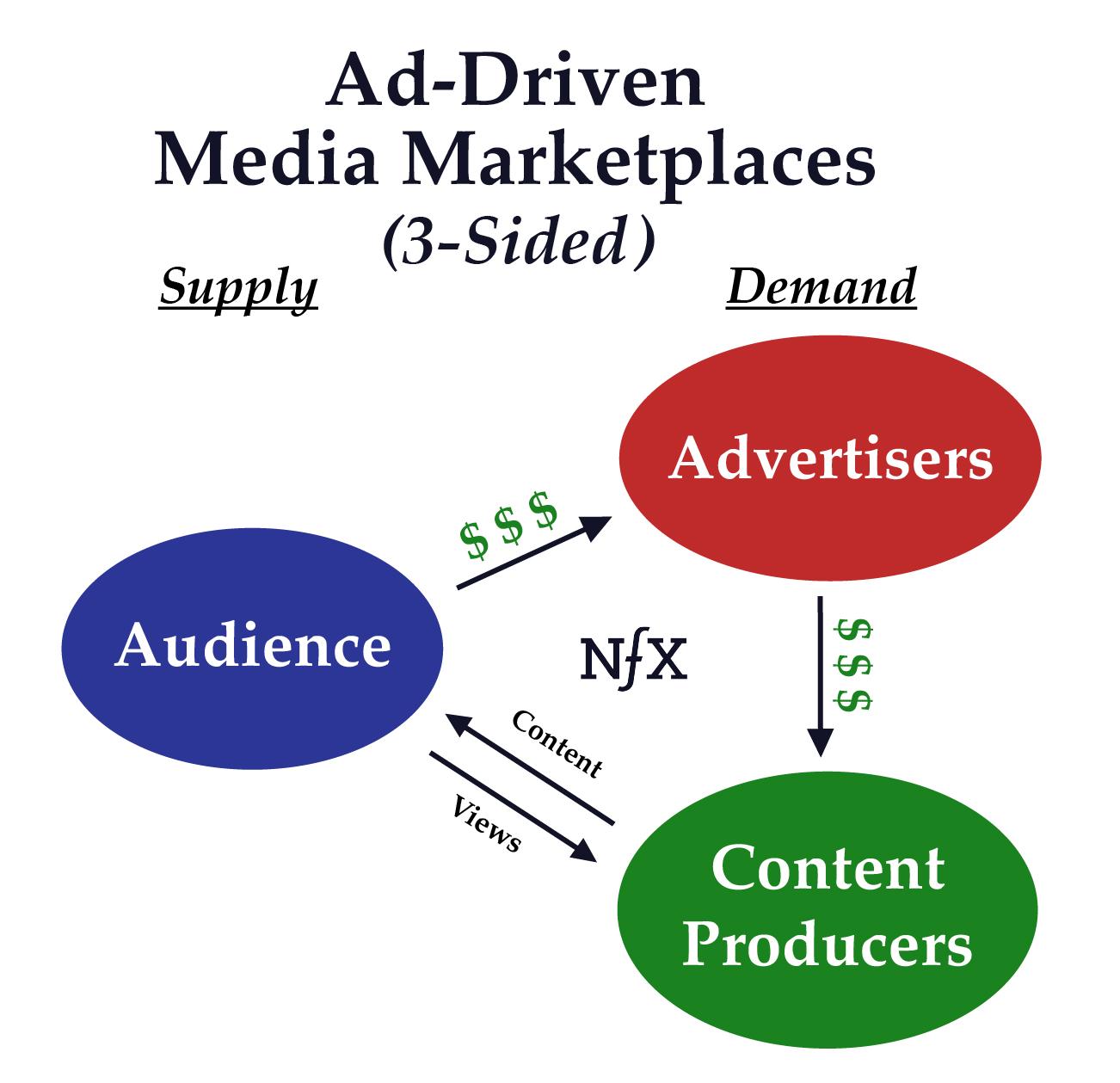

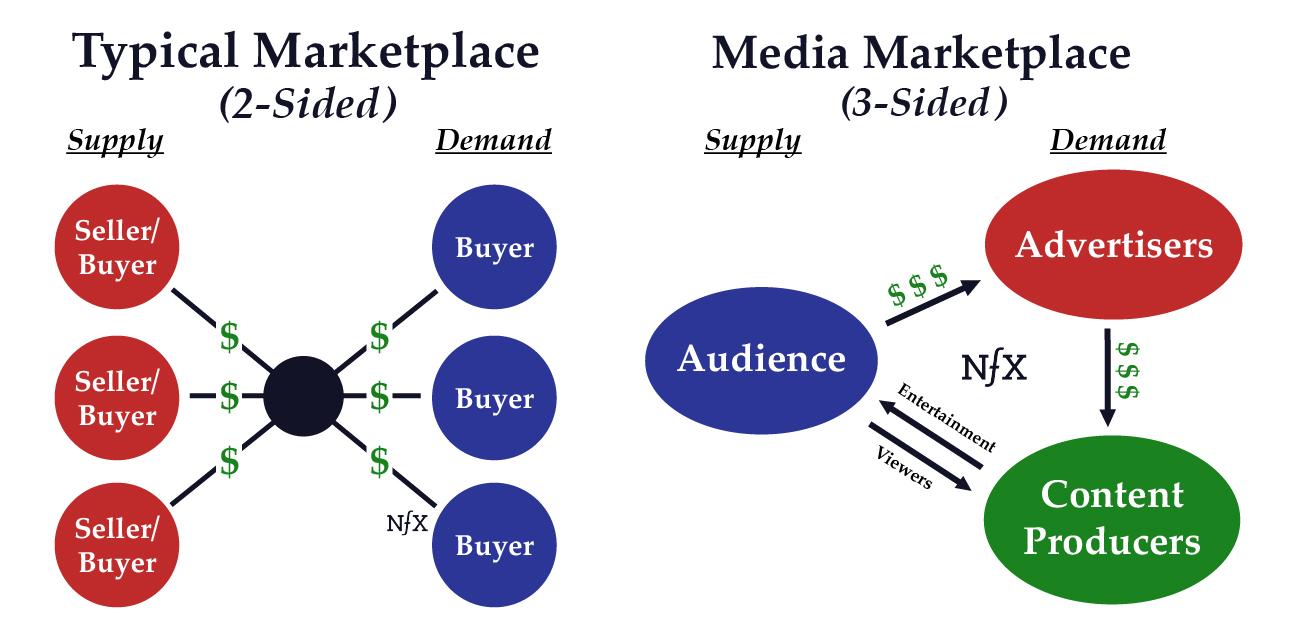

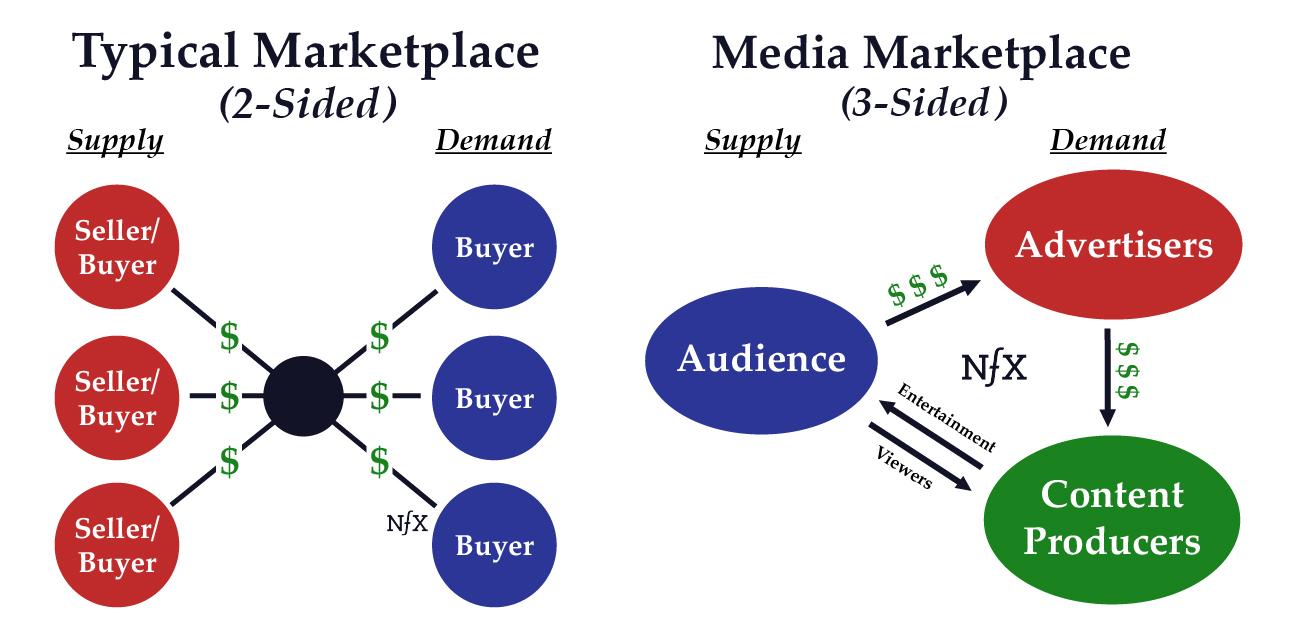

Media marketplaces are unique because they have two layers. On the surface level is a “content marketplace”, where content is the supply and attention/views/traffic/eyeballs are the demand. This looks like a normal 2-sided marketplace.

But an ad-driven marketplace adds a deeper layer, where the audience is actually on the supply side. Their attention is what demand-side nodes — i.e. advertisers and content producers — want. The addition of advertisers brings a third side to the marketplace. Your marketplace goes from matching content producers with audiences, to matching content producers and advertisers with audiences.

Of course, there’s a downside to this ad-driven model. 3-sided marketplaces are less durable than 2-sided ones. Why? Because for the content, attention is demand. When the advertisers “steal” part of the attention, the core marketplace gets less of it and becomes weaker. This is why ad-driven media marketplaces have to be careful about ad frequency.

3-sided marketplaces also make it harder to solve the Chicken-or-Egg problem. Imagine you spend a year creating good content. You make it live, and a lot of people come to see it for 2 weeks while it’s a hot topic. For you to sell ads against that traffic might take months. You never close the loop on the 3-sided market and you never have a business.

This is why video creators publish their videos on YouTube — YouTube has the 3 sides of the marketplace already — and why TV show creators sell their shows to the networks like ABC, Fox, or Lifetime. The audience and advertisers are there first, meaning that the demand and monetization model are already in place, which is why content producers come to them.

Multi-sided networks have indirect network effects, where the addition of same-side users (e.g. content producers) who you think would be competitors for attention, indirectly benefit other content producers via direct cross-side network effects that bring in more of the other side of the marketplace, the audience.

In a sense, interestingly enough, both of those types of nodes — audience and content producers — are on the supply side. Demand is the advertisers. Pretty unique dynamics that make the platform more volatile.

Another way to think about it is that the more sides you have to a network, the more indirect the network effects — meaning that the value of the network will be harder to start, will grow at a slower rate, and unravel at a more rapid rate.

This is a big reason why subscriptions present an opportunity. They simplify the network effects to two sides. Content as supply, a paying audience as demand. Simple two-sided marketplace. This is why magazines and newspapers had both subscription and advertising revenue for so long. The subscriptions were a more simple, more stable revenue stream.

The Key Attributes of Media Marketplaces

Media marketplaces describe a wide range of companies across many media formats. There are several core elements along which they differ. What’s surprising is that there are many combinations of elements that will win. It’s important to understand why these elements are significant and how they fit together so you can navigate more accurately.

The broad range of types of media marketplaces fall in different places on the spectra of several key elements.

Monetization: As we’ve said, you can choose, ads, subscriptions, or both. We are now seeing a decided shift towards mixed or subscription monetization. This will drive a lot of opportunity for the next wave of media marketplaces.

Content production: Some media marketplaces simply list the inventory of third-party suppliers. Example: early Netflix. Some create all of their own content, like the NYTimes. And almost all evolve over time. Netflix now competes with its suppliers in producing content. The degree to which media marketplaces are involved in the production of content varies both between companies and between the same company at different points in their life cycle.

For media marketplaces, curation is another important dimension here — open marketplaces vs. selected content. YouTube doesn’t curate much, but Netflix does. Twitter will curate their acceptable ads, Facebook holds a policy of curating less on ads.

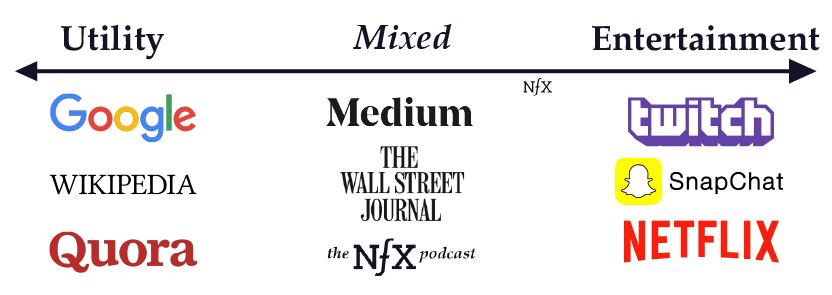

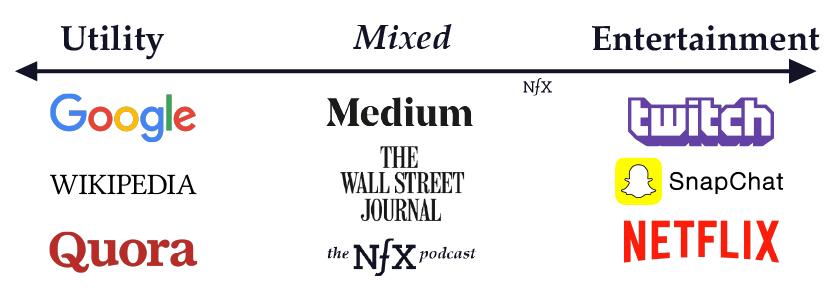

Utility vs. Entertainment: Pure utility media existed pre-internet — directories like the Yellow Pages, or newspaper classifieds, for example. Companies like Google and Craigslist perform similar functions online. Their content is focused on delivering useful information. Other forms of media, like videos and gaming, are more explicitly entertainment. “Mixed” infotainment like podcasts and news media lie somewhere in between.

It’s important to understand these different spectrums not only to understand the media landscape today and where there might be gaps to fill, but also because to succeed media marketplace companies must constantly evolve.

The Founders who succeed in running media marketplaces will be the ones who are not afraid to reinvent their whole business periodically.

Take Netflix for example. They started out with DVD delivery and then changed to online streaming. But as their margins started to shift, and third-party content producers began to pull back from their platform, Netflix had to pivot once again and move towards producing content themselves. Radical shifts and they are still on top.

Facebook, as we’ve written about before, is another example of a media marketplace that is undergoing constant and continual change. The key is for Founders to understand the options available to them and know when to shift gears.

The Evolution of Media Marketplaces

Before the internet, subscriptions drove revenues for media like cable and magazines, while other media like broadcast TV and radio were more reliant on advertising. As a result, there was a mix of two-sided and three-sided media marketplaces, but no direct network effects in media.

Internet technology led to a seismic change in media because user-generated content was now suddenly possible. The Internet, for the first time, allowed for many-to-many media – what later became known as “user-generated content.” This turned the audience itself into content producers.

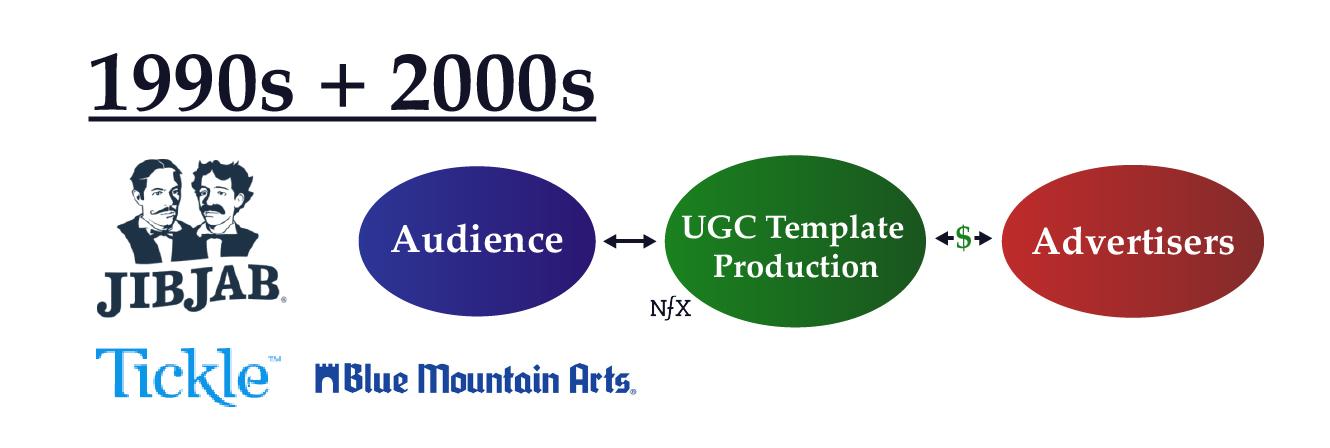

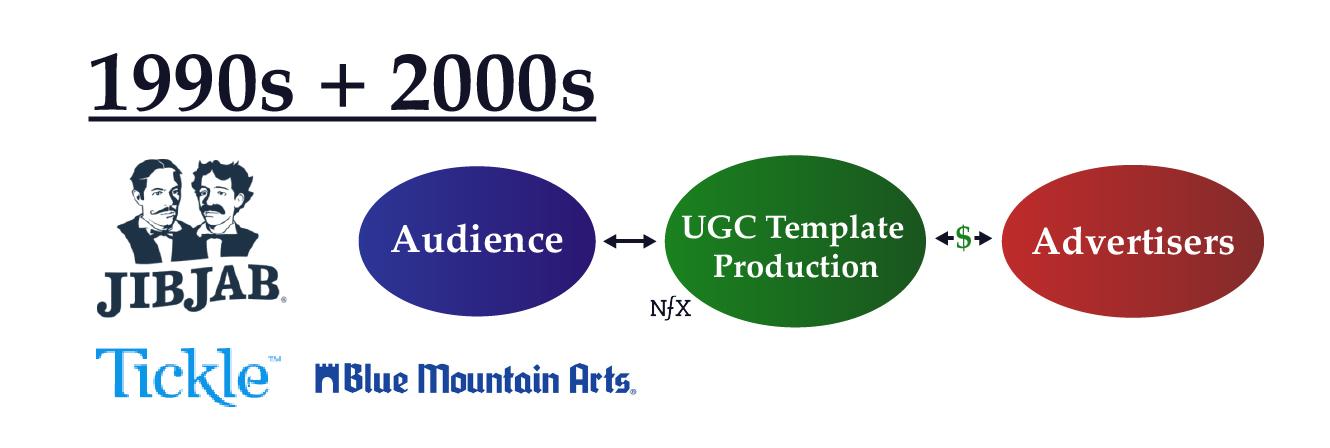

Companies of the late 1990s and early 2000s like JibJab, BlueMountain Arts and Tickle.com (which I founded) were the early pioneers in turning audiences into content producers by giving them templates for creating content. These early templates let the users customize and personalize a library of pre-built content.

However, these companies never passed the $1B valuation mark because they didn’t build sufficient retention and thus defensibility. They didn’t build direct network effects around the UGC. They created experiences that remained largely about the content and not *enough* about the network of people creating the content.

In addition, they didn’t scale well because their templates weren’t open enough. These early UGC templates were like coloring books that you color in once and leave. More content-rich templates required these pioneer UGC companies to continually produce more templates to keep users engaged, which served as a bottleneck to growth and retention.

Tickle.com, which we built, for example, allowed you to create and send quizzes to your friends. We needed to hire 50 employees, including 5 psychology and statistics PhDs, to continually build new personality tests. We called this the “fresh produce” business, and it was a tiresome treadmill. It had good viral effects, but no network effects, and thus no retention, and thus no defensibility. BuzzFeed is a more recent digital media marketplace that has similarly suffered from the fresh produce problem in the last decade, also using quizzes.

Although at Tickle we had gone part of the way towards turning our audience into content producers, we couldn’t completely extract ourselves from the production process until we moved into social networking, a more open UGC template that didn’t need to change once built, and shifted us to focus on the network of people more than the content exchanged between the people.

Our use of that template for Tickle Social Networking happened at the same time as LinkedIn, Friendster, and MySpace, and 18 months later, Facebook.

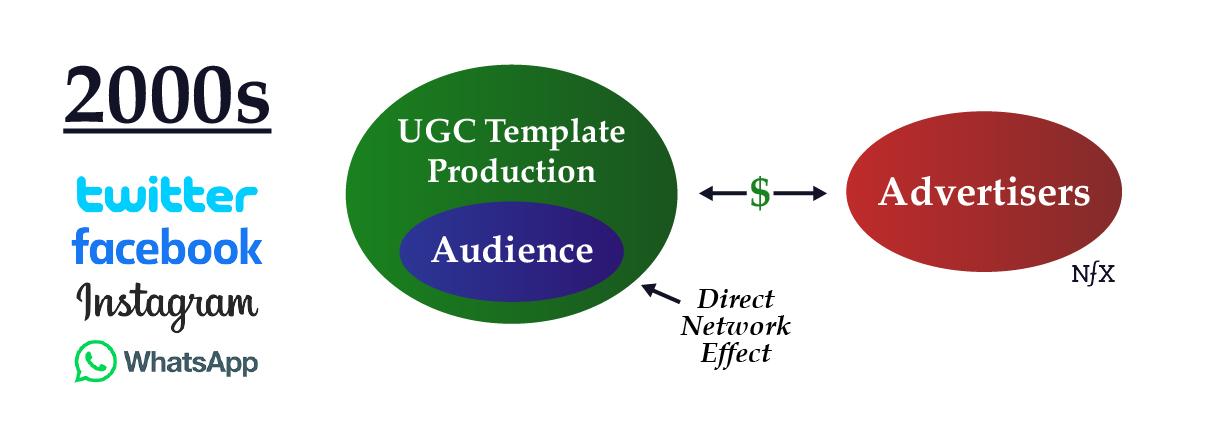

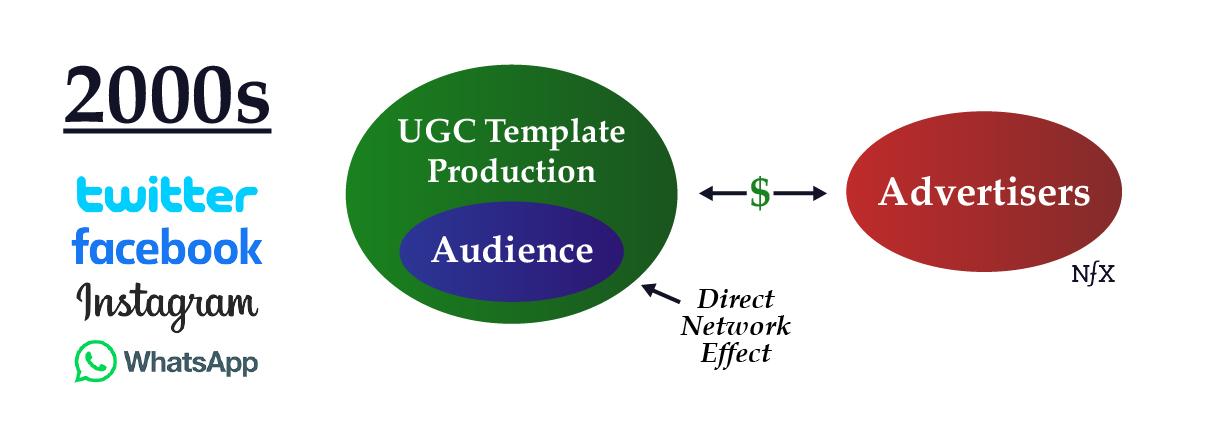

This was the big breakthrough — to build a direct network effect among your audience so they stay around and make content for you for years. Then you can take your time in bringing in the advertisers to put ads against the attention.

This new approach unleashed the direct personal nfx into the media world. It’s an atom bomb. People are still not understanding what this means for how ideas and information move in the world, as we argued here.

It’s interesting to note this trend towards more open-ended, blank canvas templates for UGC. When YouTube started, there was a 10-minute video template, and Twitter started with a 140 character limit. It was less restrictive than what came before because it was just open fields but more restrictive than now (280 character limits for Twitter and unlimited video length on YouTube). You can see the simple open text field of WhatsApp as an even more open UGC template than the FB template.

These changes in the 2000s gave rise to the iconic media marketplaces that eventually became dominant today — Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snap, WeChat, etc. But despite leveraging UGC and direct network effects, they needed to remain 3-sided because they relied on advertising to monetize.

While still technically complicated 3-sided marketplaces, these businesses are dramatically simpler to operate and to rapidly scale because your audience IS your production, so you effectively remove one of the three sides of the marketplace from an operational perspective.

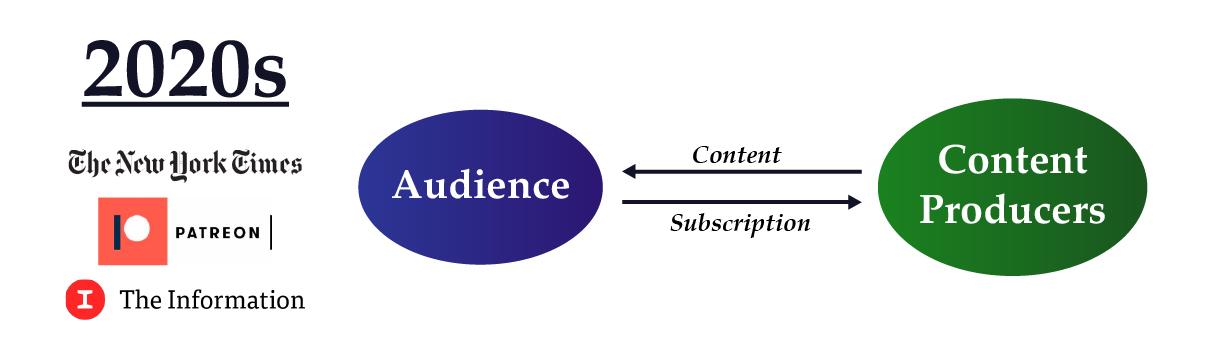

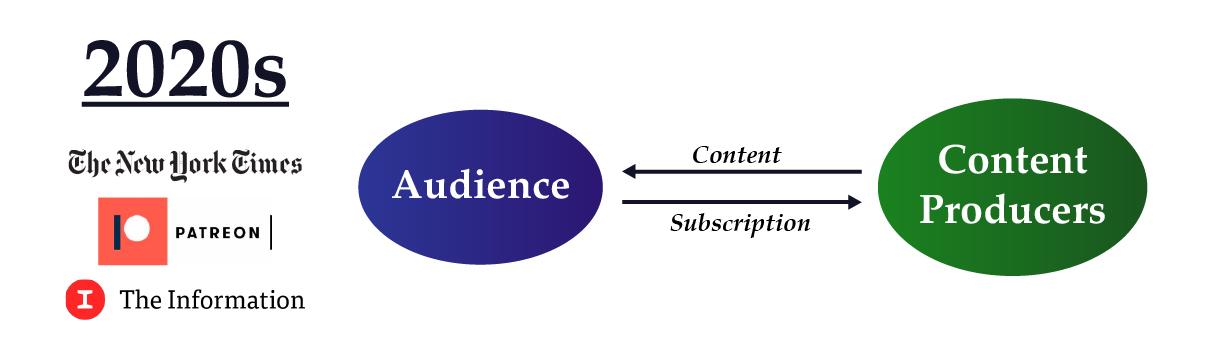

The 2020s will see the next evolution of 2-sided media marketplaces, driven by subscriptions.

Companies like Patreon, Steam, Blizzard (World of Warcraft), Disney+, Epic Games (Fortnite), The Information, NYT Digital, and Substack are examples. They connect audiences with content they are willing to pay directly for.

As magazines experienced in the 1950s – 2000s, the subscription model allows you to cater to micro-markets because a smaller audience base becomes viable when they are paying directly through subscription instead of indirectly via ad impressions.

We also expect the move in consumption patterns to move away from ad revenue media marketplaces to games. As Netflix famously said in their quarterly report in 2018 that Fornite and other games were bigger competition than Hulu and HBO.

We expect the trend to subscriptions to continue and to help give rise to the next generation of transformative media marketplaces.

Making Ads the Content

If you can get your ads to look like content to your audience, so much the better from a business perspective.

Craigslist is the best example because the content IS ads. It simplifies the operation of the marketplace dramatically. Genius, right? It’s no wonder that newspaper classifieds were the financial backbones of the newspaper industry for so long — they were free content for the newspaper that people paid them to list.

With classifieds, people pay you to give you content. That simplifies nearly everything. The advertiser and content creator are the same thing. We call Craiglist a utility media marketplace.

Google search ads are another close example of a utility media marketplace and shows again how the lines between ads and content can blur. Like the unpaid search results, the paid links at the top of the search results page often give useful information to searchers. At the beginning of Google, the difference between the free search results and a paid ad was clear. Over time, to drive revenue, they have become less differentiated. My dad can’t tell the difference at this point.

Influencers on Instagram or TikTok embedding products in their entertaining videos or photos is another example of how ads can be content, and vice versa. On Instagram, the ads work well for fashion because fashion and apparel ads are so similar to the organic content already on the platform.

Lucky Magazine, launched by Conde Nast in 2000 is another example. It’s essentially a magazine of ads.

Another example in reverse is YouTube. One of the reasons video ads are working so well on YouTube is that because users are allowed to skip the ads, it forces advertisers to create ads that are fun to watch. The ads are thus also good content.

If you’re able to make your ads valuable or entertaining, that simplifies the operations of your marketplace and makes ad revenue the right option.

14 Questions for Media Marketplace Founders

- Is your media marketplace two-sided or three-sided?

- Are you going to generate revenue with ads, subscriptions, or a mixture?

- How much can you make your ads entertaining or valuable content?

- Does your team produce content or does the content come from suppliers outside your team?

- To what extent could your audience produce content for you?

- If so, what are your templates for user-generated content?

- How open or narrow are your UGC templates?

- Can you create a direct network effect on the content-generation side (like FB and Twitter)?

- Do people come to your marketplace to be entertained or to get utilitarian information?

- Can you identify a new media unit, a new format, a new template?

- Can you identify new utility content?

- Can you identify a new bundle of content that makes sense in a subscription?

- Can you identify a piece of content that could be unbundled to attract many users?

- Can you identify exclusive content which will attract many users?

Building the Future of Digital Media

World-class Founders who understand the nuances of media marketplaces will have a great decade in the 2020s.

At NFX, we’re looking for media marketplaces in their many forms to disrupt existing media players to launch iconic new media properties. Come talk to us.

Thanks to my Partner Gigi Levy-Weiss for contributing to this essay.

As Founders ourselves, we respect your time. That’s why we built BriefLink, a new software tool that minimizes the upfront time of getting the VC meeting. Simply tell us about your company in 9 easy questions, and you’ll hear from us if it’s a fit.